I've remarked in this space before that if I wanted to, I could write a column about some cultural artifact celebrating its 50th anniversary every week. That's how the early '70s were, or seem to us who remember them.

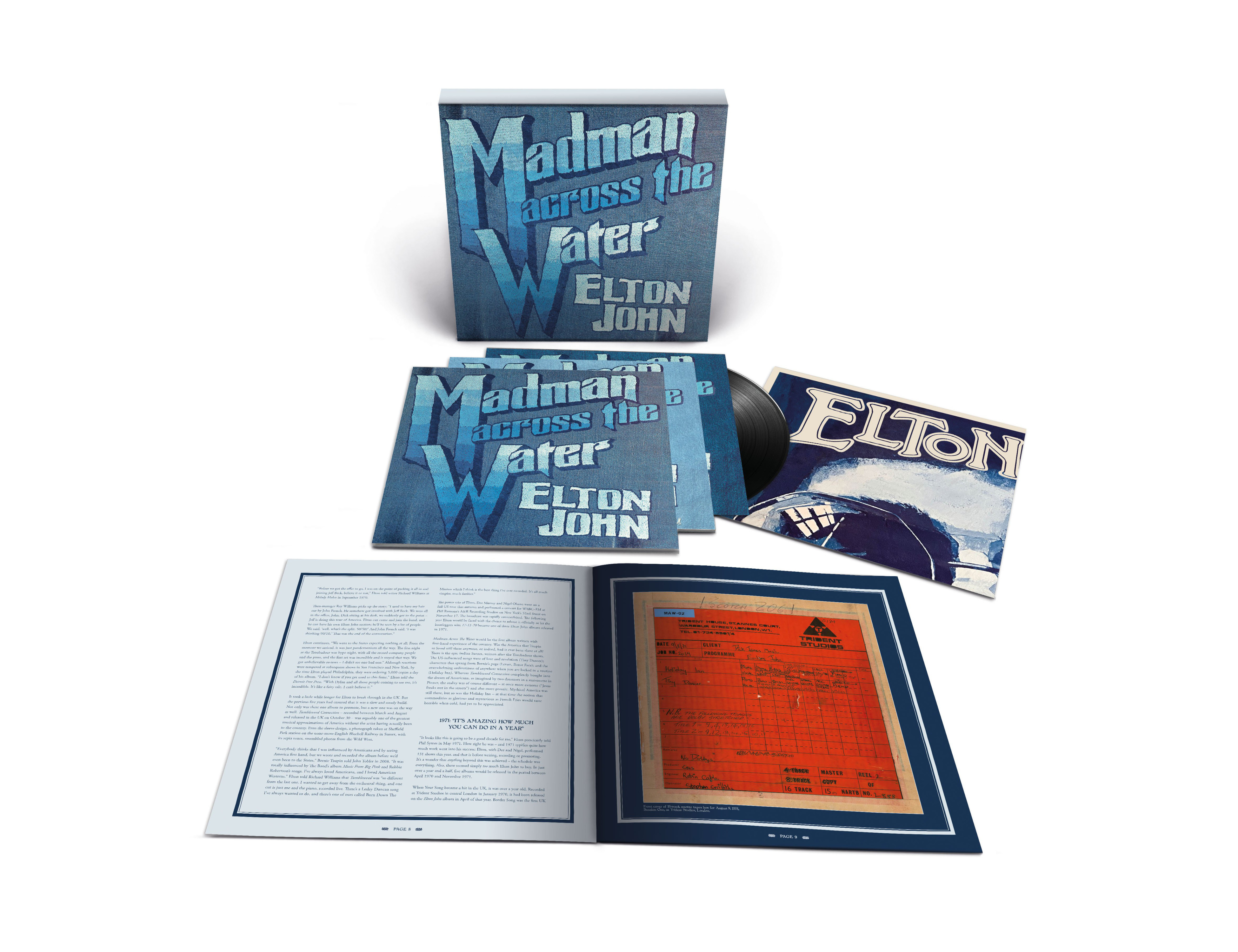

Elton John's fourth studio album, "Madman Across the Water," got the 50th anniversary treatment last week. You can buy it in a variety of formats, including a three-CD/one-Blu-ray Super Deluxe set, a four-LP box, a two-CD set, and the original LP on limited-edition, blue- and white-colored 180 gram vinyl.

There are 18 previously unreleased tracks on the most expensive versions. The set also comes with a 40-page book about the making of the album with notes from John and lyricist Bernie Taupin, and other goodies.

It's an album I bought the first day it was released, but hadn't listened to it in its entirety in probably 30 years until I started thinking about this piece. Better than I remember, it's widely considered written in reaction to John and Taupin's first trip to America in 1970. I see it as the closing chapter on John's earliest phase, marked by catchy tunes and sometimes impenetrable lyrics that nevertheless served as an effective conduit for the emotional flow of one of rock's best voices.

It was the first of John's albums to feature all the key contributors to so many of his future records and live shows: bassist Dee Murray, drummer Nigel Olsson, guitarist Davey Johnstone, and percussionist Ray Cooper. Rick Wakeman played organ on two songs.

"Levon" wasn't about Levon Helm, though you can certainly hear The Band's influence on the record. And the title track wasn't about Richard Nixon, though you can see why people might have thought that (Taupin says he wishes he'd been that clever). "Tiny Dancer" took years to grow into the iconic torch song it has become.

So I wanted to write about the album. Let's start with a story about the son of a panel beater from the North London suburb of Enfield, a guy named Norman Sheffield.

In 1967, Sheffield decided to sell the Hertfordshire record shop he'd opened after his career as the drummer for rock instrumental band The Hunters fizzled out. He had a small recording studio upstairs in the record shop, where local bands could record their music, and he liked that part of the business better than the retail game.

Tired of the small time, Sheffield began looking around for a place to build a bigger and better studio in London, one that might be used by the biggest names in pop music.

He found an old engraving works in St. Anne's Court in the Soho district, brought on his brother Barry as a partner, and sold his old recording equipment to a kid named Chris Blackwell, who'd go on to start Island Records.

Norman and Barry renovated the engraving works, bringing in the best equipment, including custom-built eight-track recording consoles (the mythical Trident A Ranges), giant Tannoy monitor speakers and a 100-year-old handmade C. Bechstein concert grand piano with a particularly bright, crisp tone.

The Beatles were among the first groups to record in newly opened Trident; on July 31, 1968, Paul McCartney sat down at that piano and began to play a ballad he'd recently written. Since the drums didn't come in until the end of the second verse, he didn't notice that drummer Ringo Starr had stepped away from his kit for a bathroom break.

He made it back to the kit in time to enter on cue, and the Beatles had a take of "Hey, Jude." They took three more passes at it that day, but that first take was the keeper. A few days later they'd overdub a 36-piece orchestra over the coda, along with a choir mostly made up of orchestra members.

Norman and Barry were paid about 1,000 pounds for the Beatles sessions (they also used the C. Bechstein piano to record "Martha, My Dear" and "Honey Pie"), but the money didn't matter; the credibility they gained by having the world's greatest pop group not only use their facility but rave about its quality led to Trident immediately being accepted as one of the best recording studios in the world.

The Beatles would use it to produce records by other artists on their Apple label; it would become famous as the studio where David Bowie recorded "Hunky Dory," "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars," "Aladdin Sane" and his "Space Oddity" single. Carly Simon's "You're So Vain" features the piano.

You know this piano; you've heard it on hundreds of songs.

The aforementioned Rick Wakeman was the first call session pianist at Trident; he played that C. Bechstein piano on a lot of Bowie tracks. He played it on T. Rex's "Get It On (Bang a Gong)." Queen used the piano on the band's first three albums — "Queen," "Queen II" and "Sheer Heart Attack" — but not, as has sometimes been reported, on "Bohemian Rhapsody."

(There's much more to the story than we can get into here. Concisely: Norman Sheffield managed Queen from 1972 to 1975, and the band split from him acrimoniously, which led to Freddie Mercury writing the over-the-top virulent "Death on Two Legs" which led Sheffield to sue for defamation. They reached an out-of-court settlement, but the bad publicity hurt Trident Studios. Eventually they sort of made up, and after Sheffield died in 2014, Queen's Roger Taylor posted a warm tribute to him on his blog.)

But nobody got more out of that C. Bechstein concert grand piano than Elton John.

MORE THAN DEMOS

When producer Gus Dudgeon first brought John into Trident Studios in 1970, their intention wasn't to record an album per se, just a bunch of demos to try to get other performers interested in recording songs written by John and lyricist Taupin.

John, born Reg Dwight, started playing piano at an early age, but wasn't exactly a prodigy. He was more a Little Richard-style hammerer than anything else; he perceived that he lacked the intricacy of a Jerry Lee Lewis. Even so, at 11, he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, allegedly after playing back, note for note, a piece by George Frideric Handel after listening to it for the first time.

As a young teenager he was playing Jim Reeves and Ray Charles songs along with standards and a few of his own tunes in a hotel piano bar; when he was 15 he formed an R&B group called Bluesology with his friends; in the mid-'60s they backed American R&B and soul acts like the Isley Brothers and Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles when they toured England. They went to work as Long John Baldry's backing band in 1966.

In 1967, Dwight answered an ad in the magazine New Musical Express seeking songwriting talent; the ad was placed by Ray Williams, the artists and repertoire manager of Liberty Records. Williams gave John an unopened envelope of lyrics written by Bernie Taupin, who had answered the same ad, and asked him to put the words to music.

Dwight met Taupin soon afterward. They clicked and, in 1968, joined Dick James' DJM Records as staff songwriters. For the next two years they wrote mostly easy-listening material for various artists, including Lulu, whose version of their "I Can't Go On (Living Without You)" was entered in the Eurovision Song Contest in 1969. (It came in sixth.)

Dwight dubbed himself "Elton John" in honor of his friend, Bluesology saxophonist Elton Dean, and quasi-mentor Baldry, and with friend Steve Brown producing, recorded his debut album "Empty Sky" for DJM in late 1968 and finished it up in the spring of 1969. It didn't make much of a dent (though the harpsichord version of "Skyline Pigeon" is pretty, and the all-but-opaque lyrics of "Western Ford Gateway" mark both Taupin's preoccupation with the American West and his penchant for suggesting a profundity that collapses upon closer inspection) and wasn't released in this country until 1975, when John was arguably the world's hottest rock star. But it was a start.

John wasn't sure what kind of artist he was going to be — he thought maybe he'd end up sounding like Leonard Cohen. But he had to make a living, so he went into the studio with Dudgeon to cut some songs they hoped would be covered by the likes of Three Dog Night and Aretha Franklin.

Dudgeon brought in arranger Paul Buckmaster to put strings on a simple ballad called "Your Song" and a sound — a sort of classical-music-with-a-blues-note, strings-in-the-lower-register-and-portentous-lyrics — was born.

Aretha cut a version of the John/Taupin composition "Border Song" that entered the Top 40, and Three Dog Night covered "Your Song," but the big hit version was John's own. It was released by Uni in the U.S. "Tumbleweed Connection," an ambitious concept album about the American West written by two blokes who'd never been across the pond, followed soon afterward. ("Tumbleweed" is an interesting country rock album — the Band is an obvious reference point — that's only somewhat undone by Taupin's willful crypticism. In some respects, it gets better the farther it recedes in memory.) Dudgeon and Buckmaster were back; the sound is sepia-toned and evocative.

Then there was a live radio concert, recorded during John's first trip to the States with his touring band — Murray on bass and Olsson on drums and never intended to be released — that got rushed out because the bootleggers got hold of it and turned it into the 1971 equivalent of a viral hit.

So they put out an official live album and the soundtrack to the 1971 film "Friends" that John and Taupin had agreed to write before their big break came out, and all of a sudden Elton John was enjoying Beatles-level success with four albums on the charts. There was some worry about overexposure.

Elton John’s “Madman Across the Water” Vinyl Deluxe Set

Elton John’s “Madman Across the Water” Vinyl Deluxe Set

A PIANO AND A 'MADMAN'

Let's go back to that C. Bechstein concert grand piano and "Madman Across the Water."

Written mostly after John and Taupin's first visit to America, "Madman Across the Water" was recorded in February and August 1971 and released in November that year, two weeks before my 13th birthday.

The first thing you hear when you put that record on is the tinkling of that C. Bechstein, appregiated C and F chords, rolling under a remarkable bluesy vocal: Blue Jean Baybay, el-lay lady, seamtress for the band.

"Tiny Dancer" has achieved iconic status, so it's difficult to believe it wasn't released as a single in the U.K., and initially only got to No. 41 on the U.S. pop charts. It had the good fortune of being released in an era when FM radio was expanding the parameters of what a radio song could be and before attention spans were attenuated by MTV jump cuts and an insidious internet culture.

It takes two minutes to get through the first two verses; at the end of the first verse John's voice and piano are joined by drums (Roger Pope), acoustic rhythm guitar (Johnstone) and, thrillingly, B.J. Cole's pedal steel guitar. At the end of the second verse, a small choir consisting of — among others — the duo Sunny and Sue, Lesley Duncan, Barry St. John, Tony Burrows, bassist Dee Murray, Olsson and Pope enter, providing a pillow-soft layer of sound.

Now we've gone from a solo piano performance to a full band, with John's intricate piano work floating above that lush cloud that, as we enter the pre-chorus section, slows perceptibly, building tension, and as Murray's bass line churns away, the steel guitar waves and peals. The drums lock onto John's marcato piano stabs and BOOM — two minutes and 36 seconds into this cinematic pop sound, we finally hit the chorus: Hold me closer, tiny dancer ....

Later, Buckmaster's strings arrive, sawing away in the lower register. And for once, Taupin's lyrics feel direct and unforced (though some of us still wonder why if she knows the words she hums the tune ... is she being modest?). And that's Wakeman on organ.

CALIFORNIA GIRLS

"We came to California in the fall of 1970 and it seemed like sunshine just radiated from the populace," Taupin told American Songwriter magazine a couple of years ago. "I guess I was trying to capture the spirit of that time, encapsulated by the women we met, especially at the clothes stores and restaurants and bars all up and down the Sunset Strip. They were these free spirits, sexy, all hip-huggers and lacy blouses, very ethereal the way they moved.

"They were just so different from what I'd been used to in England. They had this thing about embroidering your clothes. They wanted to sew patches on your jeans. They mothered you and slept with you. It was the perfect Oedipal complex."

(It's widely accepted that the song was written specifically about Maxine Feibelman, who Taupin married in March 1971, who really was a seamstress who worked for several rock 'n' roll bands and later encouraged John's turn toward extravagant stage costumes. She inspired several John/Taupin tunes and if you want to know more I encourage you to use the Google machine.)

But if "Tiny Dancer" has become the signal Elton John moment (some would argue for "Rocket Man"), there were eight other tracks on the album, every one incredibly detailed and musically rich, though the songwriting does seem to drop off a bit on side two and "Indian Sunset" sounded vaguely offensive even to my soon-to-be 13-year-old self.

My grownup verdict is that while "Madman" was a product of its time, it retains a certain power that rescues it from pure nostalgic reminiscence. It's perhaps a little baroque in places, but if, like me, you've evolved to the point where you can overlook the occasional obtuse lyric, you'll find a lot to listen to. It's remarkably detailed and well executed. Unlike some things we loved in our youth, it holds up.

Unlike that C. Bechstein piano, which was to be moved to Trident's new studio after the original location closed in 1981. But a cradle supporting the instrument broke during moving, and the piano crashed from the ground floor to the basement. It was rebuilt, but was never the same. It was sold at auction in May 2011; the purchaser (and the purchase price) were undisclosed.

Email: [email protected]