Many people have favorite movie stars and favorite musicians. For example, mine are -- to stick with the living -- the actor Jeremy Irons and the pianist Martha Argerich. However, being a bookish lad, I also have a favorite intellectual, Marina Warner. Past president of Britain's Royal Society of Literature, Warner specializes in the study of mythology, religion and fairy tales, but also writes art, film and cultural criticism, as well as novels and short stories. Of her many books, I've only read seven or eight, but each has bowled me over, especially "From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers," and "Stranger Magic: Charmed Stories & the Arabian Nights."

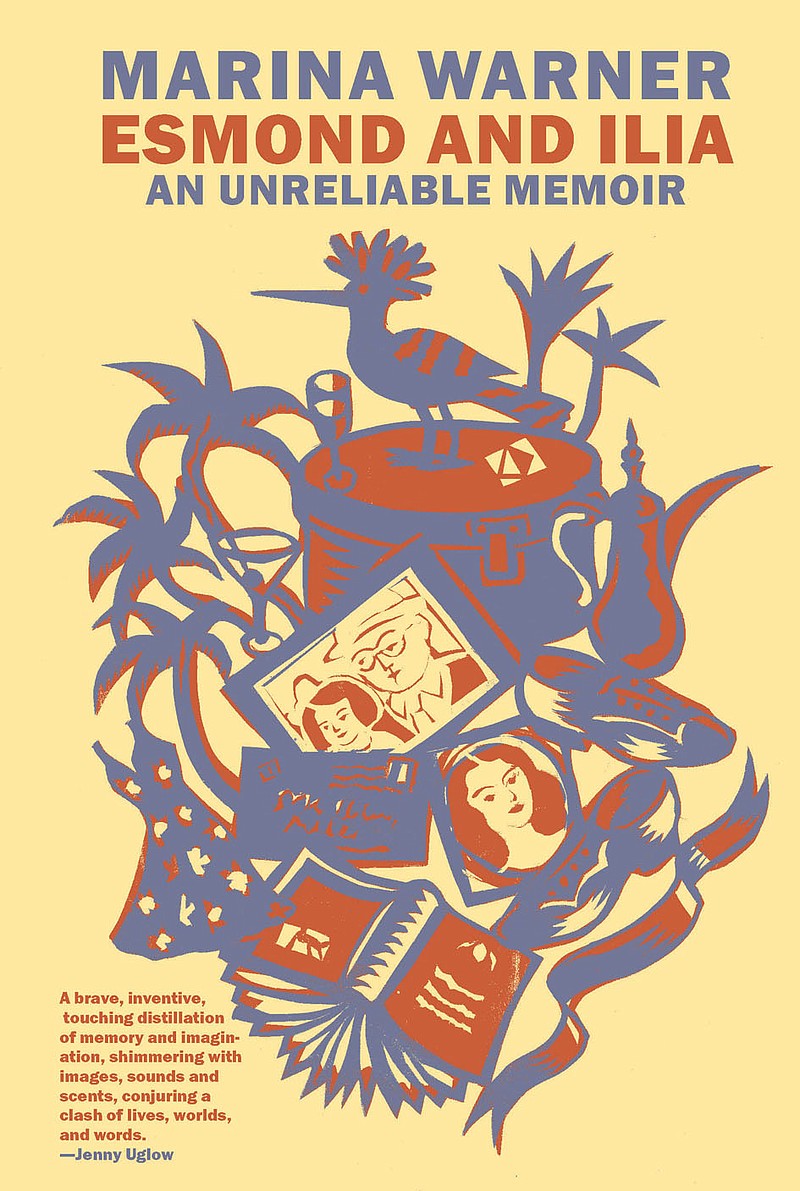

In the sheer range of her learning, Warner might be likened to the mid-20th century literary scholar Erich Auerbach; the pioneering expert on the Renaissance occult, Frances Yates; and art historian Ernst Gombrich. But only the last comes close to matching the suppleness and pizazz of her prose. To show what I mean, let me quote a longish paragraph from her latest book, "Esmond and Ilia," a double portrait of her parents during the first years of their marriage. Early in this so-called "Unreliable Memoir" -- it is largely constructed from documents, family stories and imaginative projection -- Warner conjures up the dashing young women her father typically encountered as a 1930s Oxford undergraduate. They were invariably the sisters of his college chums.

"Sisters appeared when you went away for the weekend during term to stay with a friend at his family's, they carried golf clubs and ciggies, drove quickly and tossed their gear -- tennis rackets in severe presses with wing nuts and screws at the corners, long cartons stamped with dressmakers' crests in azure and gold, in which the ballgown and the stole and the cocktail dress were lying between sheets of tissue waiting to leap out and enfold their mistress with encrusted ruffles, slippery rustling stuff, while the little strong box for Mummy's tiara which she was lending for the night, so sweet of her, was thrown on the back seat as well. Then off, off down the lanes to the country house."

At first, "Esmond and Ilia" could be a fairy-tale romance.

The son of Pelham "Plum" Warner, dubbed the "Grand Old Man of cricket," Esmond was living a feckless Brideshead-style life when World War II broke out. While serving in Italy, the bespectacled Maj. Warner -- already balding in his mid-30s -- fell in love with the utterly penniless 21-year-old Emilia Terzulli, who then spoke almost no English. They married and Ilia, as she was known, found herself quickly learning the ways of a highly traditional upper-class English family.

As almost the first order of business, Esmond takes his bride to be fitted for handmade brown leather brogues from the celebrated Peal & Company. As Warner writes, this shoe announced Ilia's "life to come in the English countryside, her formal enrollment in the world of the squirearchy ... The brogues would walk her safely on turf and moorland and through woodland and along riverbanks where the trout twinked to the surface for water boatmen and flies, and take her striding across winter fields where the pheasants whirred up, a flurry of gorgeous feathers against the unrelenting grey; the brogues would plant her on -- they would transplant her to -- British soil."

Still, there is one teeny little problem: Esmond really doesn't possess the wherewithal to maintain this grand lifestyle. At least, he doesn't in England. However, using his charm and Eton connections, he persuades W.H. Smith and Company, Booksellers, to open an outlet in Cairo, a city he knew well from his war service. As the manager of this cultural outpost of empire, Esmond is soon hobnobbing with the upper crust of King Farouk's Egypt, playing golf at the Gezira Sporting Club and sipping pink gins at Shepheard's Hotel. Well-to-do Cairo in the late 1940s practically defined urbane sophistication -- everyone spoke French, everyone smoked:

"Nobody seemed to mind smoking then -- the scent of the cigarettes delicious, the gestures involved elegant, the paraphernalia fascinating and sophisticated -- while the cigarette boxes, to which the cigarettes were transferred, were monogrammed, cedar-lined and silver."

In this worldly, decadent atmosphere, the young and beautiful Mrs. Warner immediately attracted myriad admirers. Normally, flirtation simply added spice to social interaction, but some of Ilia's "soupirants" -- French for one who sighs for a beloved -- aimed for more than a kiss on the cheek. For by her late 20s Ilia knew that her husband wasn't really her type at all.

By then, however, the family's Cairo years had reached their blazing finale: On Jan. 26, 1952, "almost every British business and most other foreign interests, especially French, were set on fire." The flames of revolution would eventually send King Farouk into exile and bring Gamal Abdel Nasser to power. Warner tells us that the sight of her father's bookstore as a blackened ruin is practically her earliest memory. At this point she brings her "unreliable memoir" to a close: She is all of 5 and her sister Laura has just been born.

Besides evoking the vanished pomp of yesterday, "Esmond and Ilia" periodically enlarges its perspective to include chapters about Victorian adventurers in the Middle East, a half-forgotten chanteuse named Hildegarde, and even the proper use of the Arabic word "malesh," the verbal equivalent of a fatalistic shrug of the shoulders. Above all, Warner is never sentimental about her parents, though she clearly loves her anxiously snobbish father, just as she deeply sympathizes with her sensitive, novel-reading mother. Not that Ilia couldn't be unconsciously cruel. She once told a plump teenage Marina that "plain girls are much more likely to be happy."

Needless to say, "Esmond and Ilia" lacks a fairy-tale ending -- after all, it's about real life -- but it is nonetheless wondrously entertaining, an ideal book for a long, hot summer.

--

Michael Dirda reviews books for The Washington Post each week.