Why is it so much easier to write a sad story than a happy one?

The simplest answer is that happy people are more likely to be out and about, getting on with their lives, instead of being holed up in some warren writing stories. Happiness is its own reward, but a lousy motivator.

There's also the distressing notion that there is something in our nature dismissing happy endings as insipid and unrealistic. Happiness is seen as simple and bland, while emotional turmoil is complex, deep, rich, and therefore more interesting to explore.

At the beginning of "Anna Karenina," Leo Tolstoy wrote: "All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

It's important to note that Tolstoy didn't imply that happy families were more common than unhappy ones; only that happy families share a common set of attributes that lead them to be happy. And unhappy families are unhappy for any number of reasons. Happiness depends on a kind of perfection, and anything short of perfection can result in interesting unhappiness.

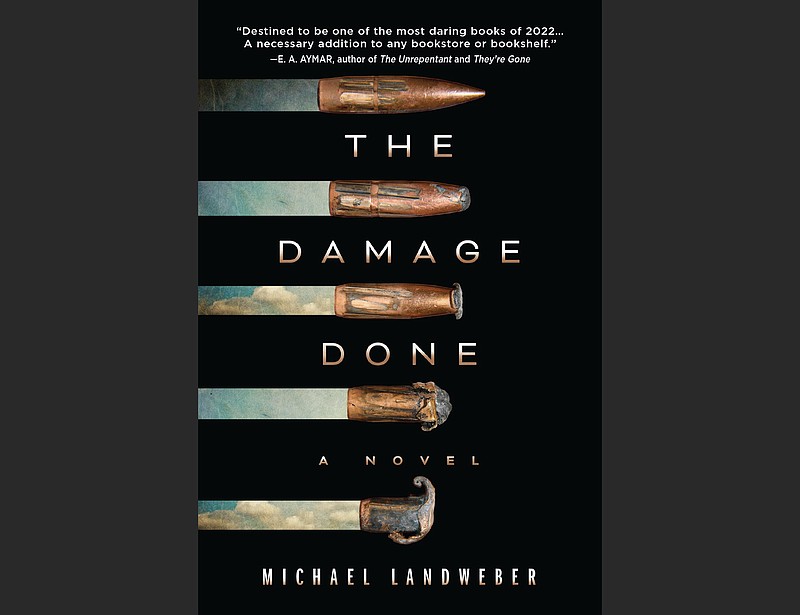

I thought about this so-called Anna Karenina Principle when reading Michael Landweber's fantasy novel "The Damage Done" (Crooked Lane, $27.99). While dystopian fantasy and science fiction novels abound, you rarely see the opposite — a utopian novel that explores what might happen if something good actually happened to mankind.

I know next to nothing about the world of fantasy writing, and I probably would have passed on "The Damage Done" had I not noticed a back-cover blurb by Kevin Brockmeier, the Arkansas novelist whose work I admire and who, if you're prone to sorting things into genre bins, might be said to write fantasy novels. I don't think of Kevin's work that way, but when I saw he had good things to say about "The Damage Done," I thought maybe I'd try out a fantasy novel.

And "The Damage Done" is a very high-concept book. It is about the end of violence — or at least the end of person-on-person physical violence. In Landweber's otherwise grounded universe, some mysterious force has made it impossible for us to hurt one another.

A bully goes to punch the bullied and the fist loses velocity and gently grazes the intended victim. Bullets hang in the air, little constellations of lead never reaching their target. The Pope wonders if "Thou Shalt Not Kill" is an obsolete commandment.

The politicians wonder how they might continue to make war.

The book lights on a series of intertwined characters. There's Marcus, a Black teenager whose brother Malcolm was the last victim of gun violence in America. Richard was Malcolm's professor, himself a survivor of gun violence, alert to the special anxiety of raising Black sons in America. Ann is a social worker and battered wife who works at an institution run by a billionaire who endowed the "Down to Gown" program that made it possible for Marcus to attend college.

The Murderer finds that the words he means to say to the parole board are suddenly congruent with reality. He will not kill again, even though he always enjoyed it before. A couple of anti-Semitic terrorists find their plans to shoot up a synagogue thwarted. A Salvadoran refugee traveling to the U.S. in a caravan is saved from gang rape when her would-be attackers find their flesh unwilling to cooperate.

The Empty Shell, a dissident writer imprisoned in an unnamed country for his diatribes against Dear Leader, finds his torturers impotent.

Questions abound, and Landweber wisely answers only a few of them. Self-harm is still possible, as a dictator and his son demonstrate. There are nonviolent forms of torture. And while something — a never-revealed deus ex machina — has rendered violence against others impossible, the human heart is still capable of racism and hate and selfishness. We can wish violence on one another; we can't execute it. In some ways, the end of violence reveals the bottomless capacity of human beings for cruelty.

We can still get our feelings hurt, we can still cause each other emotional pain, even when we lack intent. Marcus feels victimized by a society bent on turning his brother into a symbol. We can spew slurs, we can steal and destroy property. We are ingenious; take away our violence and we come up with other tools.

But in the end, thanks in part to a "10 years later" coda, Landweber's vision is ultimately an optimistic one, with lots of good days. He manages a rare trick, a happy song that doesn't feel silly or Pollyanna-ish, that embraces the entire animal complexity of our kind, and acknowledges both our habit of fear and our aptitude for hope.

Email: [email protected]