- I wish it was the sixties

- I wish I could be happy

- — Radiohead, "The Bends," 1995

On Tuesday, Peter Jackson's "The Beatles: Get Back" will be released on DVD.

Maybe that's a nonstarter for you; as odd as it may seem to some newspaper readers, there are people out there who care very little about a beat group that broke up more than 50 years ago.

And even if you do care about the Beatles, DVD sales now account for less than 10% of the movie market. Most people stream their movies, and anyone interested in the Beatles with the wherewithal to procure a Disney+ subscription has already seen this three-part documentary, which is available on the service.

Which means the Venn diagram for the potential market for this artifact might be comprised of aging baby boomers who have trouble remembering their streaming service passwords. If I'm reading our newspaper's proprietary metrics correctly, that might include a lot of you who have read all the way into the third paragraph of an essay about nostalgia, the Beatles, and Jackson's corrective (or revisionist) history of their last days.

There's a very specific target audience for a product like this: people like us; the same people who buy the super deluxe boxed sets and the coffee table books. Maybe some who have a very specific need for some physical media — it's still difficult to show a streaming movie to a class; the quality is better when you have a actual shiny disc to load into a player.

When you've spent decades insulating yourself with bookcases and racks of records and CDs, it's difficult to accept a bare-walled zen aesthetic, no matter how appealing dostadning (Swedish for "death cleaning") is in the abstract.

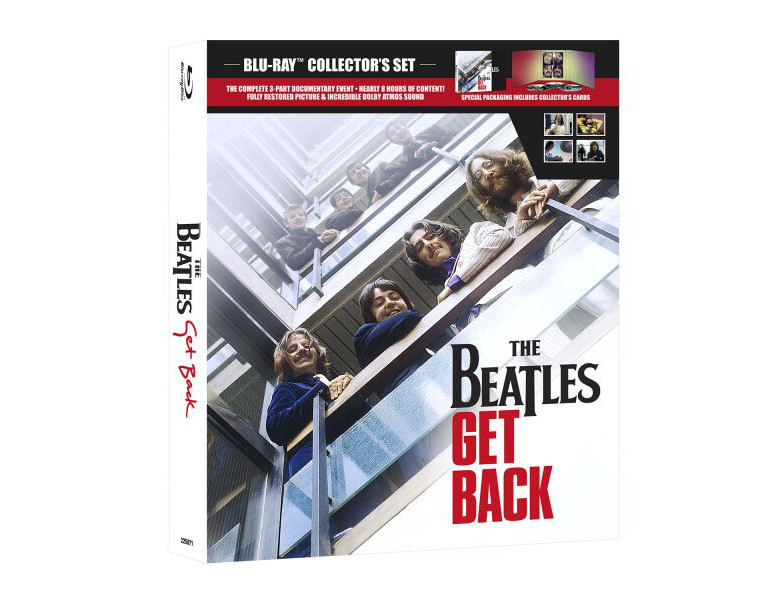

So the Beatle completists will buy the set, three DVDs for a suggested retail price of $44.95, which is less expensive than it might be, given that the total running time of the series is just under 7½ hours. Given the length, it's hardly surprising that there are no supplementary video features. There are four "collectors' cards," and the packaging is pretty deluxe.

And the movie is tremendous, even if it's not the final word on the end of the Beatles.

SLOW CINEMA

Jackson's film is in some ways an example of what some people call "slow cinema." The idea is to have the audience experience a phenomenon in more or less real time, with the camera serving as their surrogate presence.

With "Get Back," you are plunked down in a room with the Beatles and their satellites as they rehearse and create and make small talk, writing songs for a vague project that turns out to be Michael Lindsay-Hogg's 1970 documentary "Let It Be."

Lindsay-Hogg was initially engaged to film the band during recording sessions beginning in early January 1969 for a proposed television special. Those plans morphed into a feature film that's most notable for its footage of the Beatles' rooftop set on Savile Row on Jan. 30, 1969, the last live public performance of the band's career.

"Let It Be" hasn't been available on home video since the 1980s, but you can find and watch it online. I've had a bootleg copy since the '80s, and the quality of the online version is much better. But while "Let It Be" is a good enough documentary that has been unfairly denigrated by some critics (and some Beatles, especially Ringo Starr, who thought it was unnecessarily downbeat), Jackson's project has made it obsolete.

(This despite his gracious attitude toward Lindsay-Hogg's film, which Jackson acknowledges "is still a film that has a reason to exist." Except for a few specific shots with no alternate camera angles, none of the video footage from "Let It Be" was reused in "Get Back," although some of the same moments and events are covered by both films. This might produce a mildly unsettling Rashomon effect in "Get Back" viewers who've seen the earlier film.)

"The Beatles: Get Back" was originally intended to be released as a conventional- length feature film in September 2020. The covid-19 pandemic caused the release date to be pushed back a few times. Which gave Jackson and his team time to go through the 56 hours of camera footage (and more than 140 hours of audio tape) Lindsay-Hogg had recorded for his project over 21 days as they began work in Twickenham Film Studios before moving to Apple Studios in London's Savile Row.

Instead of opening in theaters, the project was designed to lure subscribers to Disney. It premiered on the service in November.

Originally intended to be released as a conventional-length feature film in September 2020, “The Beatles: Get Back” has evolved into a three-part series of about 7½ hours. Here, the Beatles play in Twickenham Film Studios during the early days of planning for what became their “Let It Be” album. A RELATABLE QUARTET

Originally intended to be released as a conventional-length feature film in September 2020, “The Beatles: Get Back” has evolved into a three-part series of about 7½ hours. Here, the Beatles play in Twickenham Film Studios during the early days of planning for what became their “Let It Be” album. A RELATABLE QUARTET

Not everyone has had the experience of working creatively in close quarters with others, but most people could relate to the ways the Beatles interact with one another. They are not unlike teammates, not unlike family. They bicker and pout and share private jokes. What's most fascinating, at first, is how ordinary they seem. They could be any four bright guys in their 20s.

But, of course, they're not. For anyone who grew up during or since the '60s, the Beatles are unmistakably their iconic selves. We don't know them, but we can be forgiven for believing that we do, given that they've been marketed to us as specific types:

John Lennon is the brash and bossy one, with an acerbic wit and (it soon becomes apparent) a heroin habit that seems to have banked his creative fire. He's never far from his helpmate/muse Yoko Ono (an artist in her own right, though often dismissed by Beatles partisans as a flaky pretender).

Paul McCartney is the natural entertainer; the cute one with the remarkable gift for melody and a weakness for the saccharine that sometimes manifests itself in what his sometimes-but-not-so-much-these-days collaborator Lennon decries as "granny music." With Lennon less driven to commanding the band, Mc- Cartney is reluctantly assuming the captaincy of the Beatles. He asserts that Lennon is "still the boss" and that he's "only a secondary boss," yet it's clear that the Beatles have become his band.

George Harrison is the put-upon little brother, whose work as the band's lead guitarist is often criticized by McCartney, who is probably a better guitarist. But Harrison has his own vision and his own songs, which are often crowded off the band's albums by Lennon/McCartney tunes. Harrison is interested in spiritual matters, and drawn to the work of Bob Dylan and The Band. He's restless as the third option, ready to strike out on his own.

Ringo Starr is the human puppy dog, a sweet cartoon of a guy who, over the course of the docuseries, emerges as the most emotionally intelligent, kindest, most professional and indispensable Beatle. Starr is a mensch, and the glue that holds the band together. He's also an underrated and very distinctive drummer who has as much to do with defining the Beatles' sound as anyone.

As time rolls on, these superficial impressions deepen and crack, as the power dynamics shift within the band. If you grew up with the idea of the Beatles and felt their secondhand presence (or mourned their actual absence) more than a few times in your life, then you might be fascinated by this long cinema verite soak, with how it explodes and cements certain preconceptions you might have held.

As you hang out with the lads you begin to to notice significant details, like the communal Fender Bass VI and the seeming ease with which they pluck indelible riffs and chord changes out of the ether. At times McCartney makes genius look banal, and even Lennon's heroin-dampened wit is sharp and nasty.

If you've ever tried to play rock 'n' roll music with your friends, you'll recognize the dynamic. And you feel humbled by how blasted good these kids were — or rather are, because film is the closest thing we've managed to a time machine, and there's a level of your brain that makes no distinction between experiencing the scene on a TV screen and actually being back there in 1969.

Still, it's probably safe to say that as big as the Beatles loom, most people probably don't care much about them. And I wonder how "Get Back" might be received by those not disposed to seeking out the immersive experience it offers.

What if your dad was insisting you watch it with him, while he adds his own running commentary about the significance of the song that John's noodling on in the corner that will eventually become "Jealous Guy"?

Non-Beatle obsessives are unlikely to come anywhere near this set, and that's fine. But for some of us, it's worth it just to see McCartney pulling "Get Back" — the song — right out of the ether.

JUST PART OF THE STORY

As good a job as Jackson and his crew have done with "The Beatles: Get Back," what they're not doing is telling the truth about the end of the Beatles. They're taking old footage, which was shot from a particular perspective, combing through it and selectively using it to tell a story — a number of stories — about the people we're watching onscreen.

Someone else going through the same material would emerge with different stories, with different characters. Jackson has acknowledged there's still a lot of footage that is worth being edited and presented to audiences. "The Beatles: Get Back" is an impression of the band as they worked together in the last days of their professional association. It's not as consistently sad as "Let It Be" mainly because it isn't as concise — more novel than short story, with a wider dynamic range. While it's perceived as a sour and even sensationalistic film, "Let It Be" doesn't mention Harrison's briefly leaving the group, which is a pivotal moment in "Get Back."

Obviously there was a lot more going on that went unrecorded, and we should always consider how any camera seems to bend the gravity in a room. Some will be drawn to it, others will shy away, and nearly all of us — even those determined to "act naturally" when fixed in its gaze — will tailor our behavior into performance whenever a camera is present.

When Bob Dylan appears in "Don't Look Back," there's no question he's acting — and that's what makes him fascinating.

This is something we need to understand about documentaries, and about journalism. In most cases it is only fair to let a subject know they are a subject; you don't want to trick them with hidden cameras or mislead them into thinking a conversation is confidential when it is on the record. So the documentary maker must assume that every one in the frame is, to some degree or another, acting.

The three-disc video set will be released Tuesday. POSING FOR THE CAMERA

The three-disc video set will be released Tuesday. POSING FOR THE CAMERA

They are posing, presenting a version of themselves to the camera. Maybe they want to seem a bit better than they usually are, maybe they want to "be seen" as a way of representing some tribe or value, maybe they want to affect an air of cool indifference. Maybe they are grinding hard to come across as "authentic."

Unless they eventually forget about the camera, which might have happened over the 21 days Lindsay-Hogg and his crew focused on the Beatles.

One way in which our technology is changing us is that we are more used to being filmed and photographed these days. Cameras are ubiquitous; we clutch one in our hands as we move through the world. It wasn't so long ago that having one's picture taken was special; now we document our loaded dinner plates.

It's not unusual for us to make our own movies, to post our videos to social media. Normalizing the attention of cameras may or may not make us less wary of them, but I'm not sure it will make us more true to ourselves, whatever that means.

Maybe the aboriginal idea of the camera as a soul thief isn't all wrong; being watched and recorded changes us.

Watching "The Beatles: Get Back," we might gain insight into how ordinary the creation process can seem, even for the highly skilled and gifted. We might appreciate how, up close, these lives and routines don't seem so different from our own, that work is work regardless of whether the bridge you're building is made of steel and concrete or tones and rhythms.

And that's valuable, especially to people who worry that their own talent is deficient.

There is mystery in every human endeavor, and some questions can never be answered definitively. Good art is more about interrogating human experience than answering questions. "The Beatles: Get Back" decides nothing. That's why it feels so honest.

Email: [email protected]