Trophies aren't hard to find at Catholic High School in Little Rock. Stroll the main hallways and you'll see championship cups aligned in lighted glass cases and dozens of plaques bolted to the walls. The most recent athletic awards even lay in state in the office before being relegated to the menagerie, linking present accomplishment to past glory.

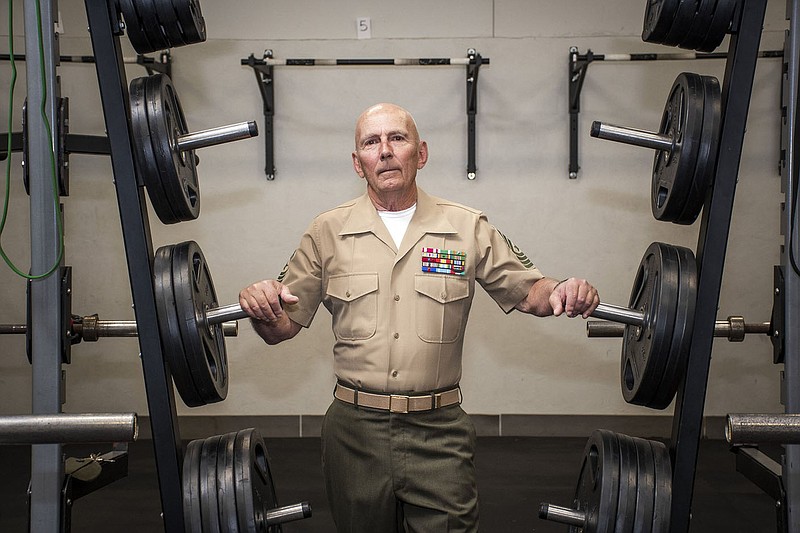

But to find the true standout here -- spoils of a program for which the term "dynasty" somehow feels too small -- takes some looking. Through the gym, down two flights of stairs, past the athletic offices, around a blind corner (it helps to have a guide), at the end of a subterranean-level hallway shared by the electrical room is the office of the Junior ROTC program and Marine Sgt. Maj. Randal Jernigan's lair.

The departmental quarters display the regimented order and precision you would expect from a Marine, which is saying something considering the office is getting no bigger yet the stash of trophies and awards continues to grow. On every measurement, from specific competitions such as drilling or physical fitness to scholarship and general excellence, CHS has compiled a record that any JROTC commandant would struggle to match.

Jernigan is an anomaly among staff here; many faculty members, coaches and staff are alumni, are Catholic or both, neither of which applies to the trim, straight-talking 63-year-old. But in many other ways he's a perfect match for the place and its high expectations for achievement, scholarship and ethos of brotherhood.

"The education boys get here is the best education they're ever going to get," he says. "The discipline, I just can't say enough, give enough praise for Catholic High School and what they're doing with these young people, turning them into young men. It's been a blessing to be at the school here, to experience it. Fourteen years here at Catholic High School has been a unique experience."

"Sergeant Major [Jernigan] came of age in the Marine Corps and that has permeated every aspect of his persona," says CHS Principal Steve Straessle. "He's lived the Marine Corps motto daily at Catholic High. He lived Semper Fi, always faithful. And when you see that model, especially when you're a young man, of somebody in charge demonstrating actual true leadership, that has impact."

75 CENTS AN HOUR

For the first part of his life, much of what Jernigan saw was outside his reach. Raised in a single-parent household in Ohio, his mother worked two jobs to help make ends meet for him and his younger brother. Despite her efforts, and Jernigan's when he was old enough, there wasn't much money to go around.

"It was rough growing up, especially in school," he says. "Everybody's got all these nice things -- and I didn't. The first job I had I was 13 making 75 cents an hour working at a golf course driving range, picking up golf balls. When I got my paycheck, I took it home to give to Mom to help pay bills. As a family, we didn't have that much."

The family's situation complicated everything, but Jernigan soon learned that if one is willing to do things the hard way, most anything could be overcome. When he wanted to join the football team, his mother approved, but said she couldn't provide rides to practice. So, he fell back on the next best thing.

"I had to ride my bike probably 10 miles to get to practice. That was one-way," Jernigan says. "I was in junior high school and I would throw my shoulder pads on my bike handles and I would ride the bike to practice. I'd get off the bike, put my shoulder pads on and my helmet and go practice, and after practice I'd get back on my bike and ride all the way back home. I got a good workout. I'll put it that way."

By the time he was a sophomore, the hardscrabble kid was starting at defensive back for Springfield Local High School in New Middletown, Ohio, near Youngstown. Football was revered in that time and place, so much so that little pressure was put on him to excel in the classroom.

"I wasn't a bad student, but back then, as long as you were a starter on the football team, teachers would never fail you," he says. "The head football coach, who was the principal, wouldn't say, 'Hey, Jernigan's not able to play because his grades are terrible.' They'd just pass you.

"Of course, it was also my fault I wasn't learning anything, but as long as I was playing football in high school that's all I cared about."

Jernigan had the heart to overcome his lack of size, but some opponents are just too tough to tackle. So it was when he found himself in senior year wondering what he was going to do after graduation.

"We'd all decided we were going to be mill rats and go work in the steel mills like everybody else does. That was our life," he says. "Unfortunately, come time for graduation, the steel mills closed down and everybody's like, 'What do we do now?'

"Mom couldn't afford to send me to school. My grades weren't going to get me any scholarships, either. Kids like us never got scholarships to go to college or anything, because the teachers weren't doing us any favors by just pushing us right along, just passing us. Got a C, yup, 'Hey, how's Friday night going to look?!' 'We're going to crush 'em!' 'OK, great. Good luck tonight!'"

Jernigan saw the only option left was the military so in September of his senior year he went to the recruiting station. He started with the Army but didn't like how he was handed a number and told to wait. The Air Force guy looked like a dork and the Navy recruiter reminded him of the Good Humor ice cream man.

"I look over at the Marine and he's standing there in full blues," Jernigan says. "I walked into the office and he was like, 'What do you want to do?' I said, 'I want to join the Marine Corps.' 'Are you in trouble with the law?' I said, 'No. I'm going to graduate.'"

Everything went swimmingly until the question of Jernigan's age came up. Being just 17, a parent would have to sign for him, the recruiter said. Convinced his mother would see the logic in what he was doing, Jernigan invited the recruiter home to get his mother's OK.

"Soon as Mom saw the Marine come in behind me, she ran to the back of the house and locked herself in the bedroom," Jernigan says. "Well, just getting over Vietnam and everything else, everybody had a bad taste about the military. And I'm begging her to come out until he goes, 'Partner, I'll give you my card. You need to talk to your mom and call me when she's ready to sign.'

"After he left, she goes, 'You're not joining the military!' I said, 'Mom, I'm not going to get any scholarships, can't afford to go to college, steel mills are shut down, what am I supposed to do? I need to make something of my life.' I kept working on her for weeks and finally she agreed. Two or three days after graduation, I was standing on the yellow footprints of Paris Island, S.C., going, 'What did I get myself into?'"

SURVIVING BOOTCAMP

Jernigan's question was answered moments after the bus loaded with new recruits whined to a stop and a hulking drill instructor climbed aboard.

"Welcome to Paris Island," the man said. "You've got about half a heartbeat to get off this bus and get on my yellow footprints and you don't want to be the last one.'"

The simple directive pushed Jernigan's heart to his throat. He'd told himself he would not give them a reason to yell at him, that he'd survive boot camp by being first in line to everything. That included getting on this bus which now meant he was stuck behind a writhing morass of fellow future Marines.

"People were trying to go out windows and I'm trying to crawl over seats," he recalls. "I was the last one off the bus. They kicked me off the bus. 'Get on them footprints!'

"Then, they herded us into a wooden building where we had to empty our pockets. They were looking for contraband and all this garbage. Back in those days I used to have a fake ID so we could buy beer. Of course, I never took it out of my wallet. They tore through my wallet, 'What's this? How old are you? You won't need this no more!' And they took it from me. I was like, 'You idiot.'"

This shaky start aside, Jernigan quickly fell into stride at boot camp and over the course of the training formed strong bonds with his fellow Marines. He also developed a deep admiration for his senior drill instructor. For the poor kid from the Rust Belt who grew up without a father, the man he still only knows as Staff Sgt. Downing was a potent influence.

"He took care of us, he was your father figure," Jernigan says. "You wanted to keep him happy because the junior drill instructors, they were nowhere near as good. You respected him. You would do anything to please him. You really didn't want to make him mad. Believe it or not, I didn't want to graduate. We'd become real tight as a unit and a band of brothers."

At graduation, Jernigan introduced his mother to Downing, a moment that still brings a gleam of pride to his eye.

"I walk up to him and said, 'Excuse me sir. I'd like to introduce you to my mother.' He goes, 'How you doing, ma'am?'" he says. "Then he looks at me and he says, 'Well, Franklin, you did a good job.' My mom looked at me and I looked at her and as we walked away she goes, 'He didn't even know your name.' I said, 'I did what I wanted to do.'

"There's only two ways they're going to know your name, a drill instructor. You're number one in the platoon or the screw-up in the platoon. I was right in the middle and he didn't remember who I was so I did a great job."

TAKING SECOND

Jernigan attended Engineering School at Camp Lejeune where he learned how to work on heavy machinery. Aside from a stint in Okinawa, Japan, he spent his military career in the states where he served a variety of roles, including as a highly effective recruiter. He retired in 1999 and returned to Ohio where he got the idea to teach high school. Six years later, tired of the winters, he landed a job at Pulaski Academy and four years after that, Straessle hired him to take over Catholic's JROTC program.

But it wasn't until a 2013 phone call that Straessle truly understood the type of guy he had running his program. By then, Jernigan has taken over coaching the school's JROTC physical fitness team -- a competitive squad that scores points for completing timed basic calisthenics such as situps, pushups and a timed run.

In his first three years at the helm, Jernigan had delivered three-peat national titles. But as he answered this particular call, Straessle detected an unfamiliar edge in coach's voice.

"I let you down," Jernigan said curtly. "We took second."

"What?" Straessle stammered.

"We took second," Jernigan fairly spat out the words. "That's last place."

"Sergeant Major, that's second in the nation, for crying out loud," Straessle replied, scarcely believing his ears. "Just relax."

"No, you don't understand. If I ain't first, we ain't nothing!" Jernigan replied. "I want to be a champion and the boys want to be champions."

The exchange was more than mere hoorah bluster by Jernigan, who believed deeply that to do something right was to do something well, to one's best abilities and maximum potential. Catholic High had shown itself a school capable of producing national championships and the 2013 team was no different from its predecessors, save for lacking the mental toughness to claim its destiny.

"We'd have won if the boneheads would have listened to me," he says. "Five situps cost us the national championship in 2013 because [the athlete] wasn't coming all the way up and the judge is going, 'Nope. Come up farther. Nope, nope.'"

You chuckle. Sgt. Major does not.

"Wait, it gets better than that. Three pullups the following year cost us the national championship. Instead of pulling all the way up to his Adam's apple, he was trying to stretch his neck. He must have done 35 or 40 pullups and kept trying to stretch his neck instead of just pulling straight up. Wouldn't count them. Nope."

BACK ON TOP

Whatever those two near-misses did, it stuck. Jernigan and his squads would not lose again at the national championships. In all, he's led nine teams to a national title, plus two more squads from Mount St. Mary Academy in both years the school fielded a girls team.

"I was just as hard, if not harder, on them than I was the guys. And the girls loved it," Jernigan says. "They knew I was showing interest in them, and I wanted them to succeed. And those girls, they would push the boys! They would say, 'Suck it up, buttercup! Quit whining and do your exercise!'"

"It was so cool to see how he worked with the kids and to learn that from him," says Rebecca McWilliams, who chaperoned the girls teams. "He would be right up there encouraging them and pushing them. But then he'd step back and just let them work with that confidence he had in them. And I think the kids could sense that too and they appreciated that. It wasn't a puppet master pulling on their strings. It was 'you've earned this, now go get it.'"

Jernigan's 2022 national title, which for the first time was contested on Catholic's home field, was as much a coronation as championship. The home team thrashed visitors by nearly 200 points and placed five of six team members in the top 10 in individual scoring, including four of the top five individual slots. To a man, team members said the motivation for such a showing was to honor their coach.

"It meant everything," Sam Robinson says. "I've been working up to this for three years. I'm glad I got to do it for him."

"It was pretty amazing," Christian Dawson adds. "It was my first full year of physical fitness at Catholic. It is an honor to be a part of (Jernigan's) legacy here because he's done so much, and we're proud to support him."

The competition took on an additional emotional element as everyone in the program knew it would be Jernigan's last, having announced his retirement from Catholic High earlier in the year. As he goes, he leaves behind hundreds of JROTC students who have grown into men and a national legacy that will be hard to equal, one built on a surprisingly simple philosophy. Ask him for his secret formula over all these years and he breaks into a broad smile.

"People always ask me that, 'What's your secret? Can you tell me what you do?' I always say, 'You haven't heard about it?'" Jernigan says, leaning in conspiratorially. "'It's a new concept. It's called W-O-R-K.' I've always tried to teach the kids, if you put in the work, you'll get the results. If you don't put work into your family, you're not going to have a very good family life. If you don't put the work in for your education, you're not going to get the benefits.

"As a coach or a leader, you've got to make them believe that they can achieve it. But once they see it's within their grasp, they want to go for it."

CORRECTION: Marine Sgt. Maj. Randal S. Jernigan attended Engineering School at Camp LeJeune. The name of the camp was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.