One of Garland County's oldest and tallest residents has fallen.

She stood for more than 120 years in a small copse of trees in the Indiandale neighborhood of Hot Springs. She fell with a booming sound on a windless Sunday afternoon as her human neighbors were sitting on their porches. When they went to examine the place where she fell, they found her prone, lying stretched out, 110 feet across the earth.

It was not difficult to determine what brought the venerable denizen of the forest to her resting place, for the base of her trunk was decayed, diseased and degraded. The only mystery: How had she survived a violent storm only weeks earlier?

Had the ancient loblolly pine tree (Pinus taeda) been felled by the perpendicular cut of a logger's chainsaw while she was still living — with sap running up and down her vascular system -- it would have been relatively easy to count annual rings to determine her precise age. However, that was not the case. The split and splintered remnants of the tree's trunk at the base were jumbled. Much of it had been reduced to sawdust.

Only by counting disconnected, flaky, paper thin, insect damaged remains was it possible to estimate the number of those annual rings — more than 90.

However, according to Eric Sundell, editor of the 2014 edition of Dwight Moore's "Trees of Arkansas," small seedlings growing in a forest with modest shade might grow exceedingly slowly, for decades. Seedlings under such conditions form annual rings so tiny they are detectable only under a microscope.

So, the 90-year estimate based on visible annual rings for this tree is likely an underestimate of the tree's life.

[RELATED: Is a tree a ‘she’? See arkansasonline.com/0117she]

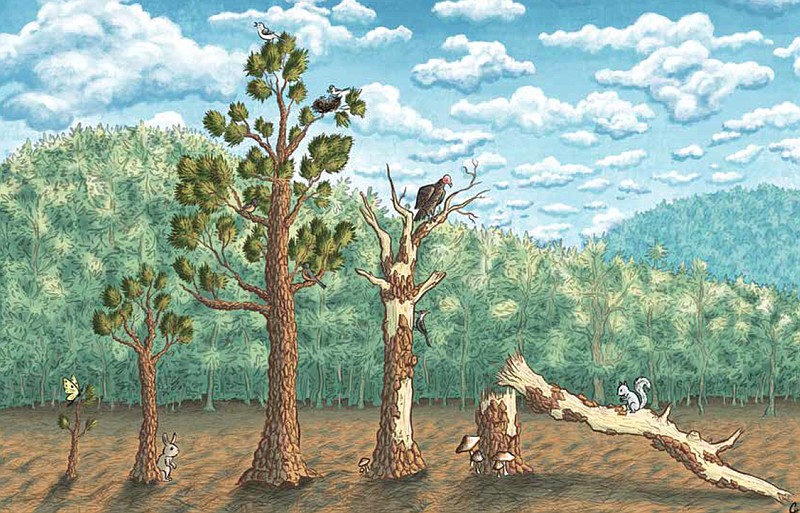

Even after death, a tall old tree is still a vital link to the biosphere. After she quit bearing cones and forming annual rings, she stood with no pine needles and began shedding her bark and smaller branches — not giving much shade, but still providing refuge to birds and small forest creatures.

Human neighbors took no precise note of when she actually died. Some claim to have known her while she yet bore pine needles, but for at least 10 years more she stood only as a barren snag.

Towering above the nearby oaks, her naked limbs have been a favored perch for owls at night and hawks by day. Woodpeckers have carved their homes in her pulpy, decaying wood. Countless generations of insects have existed beneath her bark.

Given the time that this ancient lady may have spent struggling to survive as a seedling under the canopy of deciduous trees; and the 90 years of rapid growth she spent reaching for the sun and sending her roots deep into the soil, removing carbon from the atmosphere, and enriching oxygen for human consumption; and the decade or more that she has stood as a post-mortem snag, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the seed that germinated to first give her life fell to earth in 1900.

SEEDLING

In 1900 she would have been one of the last generations of seedlings fertilized by droppings from the great migrating flocks of the now extinct passenger pigeon. A year or two later, when she was just a switch of a tree — and had avoided being eaten by an insect, deer, rabbit or feral hog — a low flying Carolina parakeet could have perched briefly on her spindly trunk before flying off to ravage someone's vegetable garden.

[Gallery not showing up? Click here to see » arkansasonline.com/0117tree/]

By the time she became a sapling in 1925, the last pigeon and parakeet had died in a Cincinnati Zoo.

Presuming that the seed that gave her life was not carried a great distance by wind or an industrious squirrel, we can say that a railway constructed in 1887 passed her parent trees to the north a decade before she was conceived.

Ten years later, in 1897, the oldest golf course in the state of Arkansas was built less than a quarter of a mile away. Had its builders chosen to construct the course across the street from where they did build it, she would have been dozed down to make a fairway. Instead, it was thousands of her sister and brother trees that lost their lives on the ridge to the southwest so that famous baseball players have a place to golf.

She sent down her first roots only four blocks east of Malvern Avenue and south of Comanche Court in a low area unfit for cultivation, beside a creek so small that it dries up in summer. The land around her is subject to flooding after heavy downpours.

There is some evidence that at the turn of the century, the woodland plot where she grew was a place where cows and horses were pastured.

In the 1930s this land was owned by Frank Niemeyer of Niemeyer Lumber Co. In a deal cooked up on the golf course, Niemeyer ceded the rights to develop it to Dane Harris, a notable gambling boss turned real estate mogul. Residential building began in in the late 1940s. It was Harris who dubbed the area "Indiandale," named the streets around the tree after Indian tribes, and selected the head of a bonneted chief as the development's logo. However, the site has no particular connection to American Indian history.

Harris developed the more favorable building sites along the hillsides near roads first. The plot where the tree took root was destined to become a tiny, land-locked, forested island inside the city limits of a village that was growing increasingly urbanized.

SAPLING

On Aug. 25, 1916, Congress established the National Park Service, and Hot Springs Reservation came under its administration.

At the time, the legislation had no impact at all on the well-being of loblolly pines, but eventually Congress' action would affect the way humans looked upon all naturally occurring things in Hot Springs. Preserving the "hot spring" per se was the legislation's central concern, however, protection eventually expanded to include all plants, animals and minerals in the National Park. Though the trees that grew in Indiandale were only near the park boundary, all living species benefit when special care is taken to protect part of the natural heritage.

During the 1930s and '40s the sapling matured into a plant that could reasonably be called a "tree" by humans who viewed her above the ground. Below ground, her roots were spreading down and around to find mineral nutrients and water to quench her thirst. Through those roots, she was becoming enmeshed in a secret network of chemical messaging conveyed through fungi.

Roots facilitate the network whereby plants of differing ages and species communicate with one another. That fungal network was not known or understood by the Arkansas Forestry Commission which was established when the tree was 30. However, now, given scientific advances described in "The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel and How They Communicate" by Peter Wohlleben in 2015 and "Finding the Mother Tree" by Suzanne Simard in 2021, an awareness of the importance this fungal network stimulates a promising new area of insight for forest health managers.

SISTERS

This loblolly pine did not grow alone. Three of her loblolly sisters stand nearby. Judging from their size, the sisters were a decade younger. She was the tallest. All four grew in a row, which when viewed from afar made it appear they were planted by some human hand, but when viewed by someone standing in their shadow it is apparent they sprang up randomly.

There is only one young pine in the immediate vicinity. This single, crooked, sickly looking loblolly sapling grows 150 feet southwest of where she stood, and it is likely the offspring of a sister tree. In mature forests, though a tree may produce millions of seeds, on average only one other tree that is its offspring will reach full seed-bearing maturity.

A cursory look at other flora thriving in the copse found persimmon, American elm, American holly, rattan vine, Virginia creeper vine, greenbrier vine, post oak, willow oak, mockernut hickory, black cherry, sweetgum, sugarberry and green ash. Their size indicates that in 1950 many of these trees, vines and bushes kept company with the then-young loblolly sisters.

Also present are invasive plants that were not around when the old loblolly was a seedling. These include privet, nandina and Japanese honeysuckle. Just as the coming of the white man interrupted the flow of the civilization among American Indians in the Caddo Valley of Arkansas where the pine grew, so such introduced plants have degraded and hindered the health of native plants in urban woodlands.

At the zenith of her life, perhaps in the 1980s, before she began her decline, the fallen loblolly of Indiandale grew to an impressive size. Her 110 feet of height do not qualify her as an Arkansas champion tree, however. The Champion Loblolly pine in Arkansas lives on private ground in Howard County. At chest height, that tree is over 5 feet in diameter, almost twice the breadth of Indiandale's pine, and it is 30 feet taller than she was.

"Most pines are tall and thin with scarcely more than 30 feet crown spread," says J.T. Simmons. "The state champion tree is bifurcated, indicating that the area was likely harvested years ago, but the tree wasn't valuable because it split low. In fact, many of our largest trees were saved from the initial logging in Arkansas because they were not valuable to harvest."

Simmons is a young arborist with Hot Springs roots, who at age 16 has already discovered and verified seven species of Arkansas Champion Trees. Simmons notes that "the United States Champion Loblolly pine is in South Carolina, standing at 168 feet and estimated to be 300 to 350 years old. Seriously impressive!"

The tall tree that is the subject of this essay began dying about the time J.T. Simmons was born.

At some point in the Indiandale pine's life, it sustained an injury that did not affect her sisters. It may have been a lightning bolt that she took because her head reached higher than surrounding trees. Or, maybe ice weighted down one of her branches until it ripped away bark from the trunk, causing the wound. Another tree in the area may have fallen, hitting her and scraping the bark away, creating an entry point for insects. Or perhaps a neighborhood child with a hatchet chopped at the tree. The tree was too mighty to be felled by a child with a hatchet, but the wound a child might inflict could eventually lead to a tree's demise.

In the early 1990s, an invasive pine beetle began attacking trees in Canada. From there the infestation began to spread south, and in the late '90s, it showed up in Arkansas. The pine beetle victimizes damaged and weakened trees.

Wounds in bark allow it to enter the tree. Once inside, it tunnels beneath the bark and lays its eggs, and later the larvae eat away the life-giving parts of the tree that lie between the bark and the solid, wooden trunk, which gives the tree its structural strength.

Given enough time, the pine beetle larvae girdle the trunk and thus snuff out its life. That, it appears, is what happened to the tree that stood in Hot Springs' Indiandale neighborhood.

SNAG

Though she was dead by 2010, she still stood. Had she grown too close to a house, building or power lines it is likely that a protective homeowner or utility worker would have felled her. But since she was not, she became a snag.

A snag is a dead or dying limb or tree that's prominent in a landscape. As a snag ages, its wood softens and it can more easily host insects. Woodpeckers can excavate the wood of snags more easily than solid, live trees to make their nesting cavities. And because the snags no longer bear leaves, birds of prey can perch in the warmth of the sun and not have their view of the land below obstructed -- making it easier to find prey.

Red-tailed hawks perched on that tree occasionally, and a red-shouldered hawk that nested nearby hunted mice and chipmunks for its young from the same snag.

In spring 2020, three social-minded Mississippi kites landed on the snag after swooping all around the area catching dragonflies. Ten or twelve crows raised a ruckus cawing while perched there one day, and were soon harassed by a mockingbird who, though he was outnumbered, gave a plucky account of himself. That mocker drove the crows away.

Pileated woodpeckers foraged in the cracks of the snag for ants and insects.

Ominously, a few days before she fell in spring 2021, a sunning vulture perched atop her with wings outstretched like the top-most carving on a totem pole.

When the snag and the entire tree finally came crashing down, the nesting cavity of a downy woodpecker was found chiseled into the trunk.

SMASHING

In crashing to the forest floor, the loblolly pine made a valuable contribution to the surrounding biosphere.

As she fell, she bent back the limbs on surrounding trees, crushed away the vines that were strung between some trees and made a hole in the understory. Life-giving sunlight could shine once again on the soil to stimulate seeds that slept dormant among fallen leaves.

With photosynthesis and new space, the cycle of life could make full circle.

A dead tree rotting on the forest floor is just as vital to woodland habitat as a seed-bearing live one. As the loblolly pine decays, she will nourish the plants, foraging birds and fungi. In death she will bolster the soil. She will nourish existing and new organisms alike.

Legacies left by her human Garland County contemporaries — such as Hill Wheatley (1894-1993), for whom streets and parks are named; Sid McMath (1912-2003), war hero turned governor; publicist Alta Smith (1888-1963), who made Hot Springs a tourist destination — continue to enrich the community years after their passing. And so, too, it is with the loblolly of Indiandale.

Jerry Butler writes frequently about Arkansas birds and the people who enjoy them. Share your stories with him at