- Ain't there one damn song that can make me

- Break down and cry?

- — David Bowie, "Young Americans," 1973

An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. — James Baldwin, "The Doom and Glory of Knowing Who You Are," Life Magazine, 1963

If you remember Dean Friedman, it's likely because of a song called "Ariel" that was a hit in 1977.

It's a good song about a guy (presumably Friedman) and his romantic adventures with a quirky vegetarian Jewish girl given to wearing peasant blouses "with nothing underneath"; getting high and singing "Ave Maria," that unfortunately gets lost in the mix of the flood of soft rock singer-songwriter material of the time. Those were the days of Henry Gross' "Shannon" and Leo Sayer.

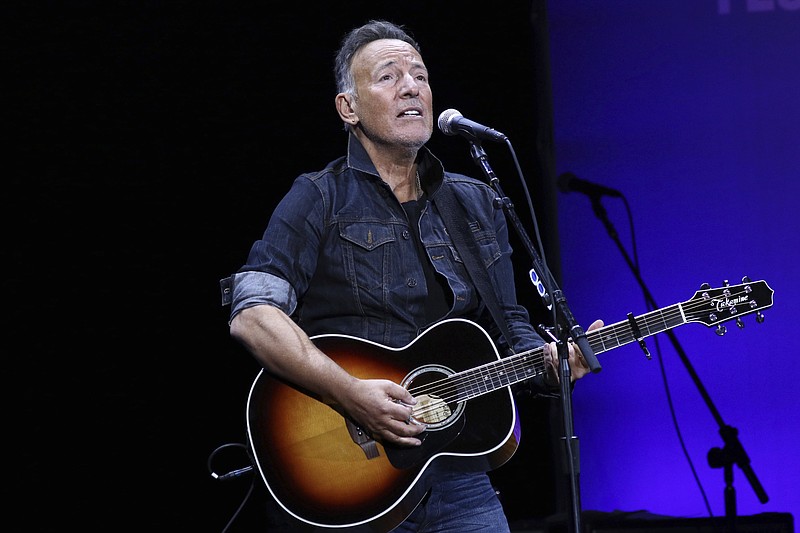

But Friedman has more in common with his fellow New Jerseyan Bruce Springsteen than that ilk, with his evocation of old-time rock 'n' roll ("Ariel" even has a nice saxophone solo, though it runs more toward Boots Randolph than Clarence Clemons) and the precision with which he tailors his material. Friedman fits words to pop music; he doesn't settle for easy rhymes or catch-phrase cliches.

"Ariel" is a crafted work, crammed with specific detail that listeners in the greater New York City area could recognize, such as a waterfall at the Paramus (New Jersey) Park Mall, a reference to listener-supported radio station WBAI and schlocky late-night horror movies airing on local Channel 2. When I heard the song I was thousands of miles away from the places Friedman was singing about, but I understood them as concrete places and institutions.

Were I ever to teach a songwriting class, I would likely use "Ariel" as an example of an honest pop song that resonates with a wide audience because it is so well-observed. (It also has a killer melody.) While I don't know if it's based on an actual date the author had with an actual person (Friedman once said it was a "composite" of all the dates he had as a teenager), I have no doubt that very little of it is fabricated.

But "Ariel" isn't the first song I think about when I think about Dean Friedman, who I think about more than you might suppose, given that he's most often described as a one-hit wonder (wrong, there were two hits) in the U.S. (In some circles in the U.K., he's regarded as a legendary singer-songwriter.) We've never met and I've never seen him play live. Friedman still tours, and he keeps up his website — deanfriedman.com. We can surmise he's had a long and successful if somewhat-under-the-radar career in music. I think he once re-tweeted something I wrote that mentioned him.

The song I most associate with Friedman is "Song for My Mother" on Friedman's eponymous debut album, the same record that spawned "Ariel."

It's a stark track, just Friedman's voice and acoustic guitar. It's naked, emotionally and in terms of production. The lyrics are raw, Friedman's voice a shivery, needle-ly thing working its way back and forth as it cross-stitches a devastating portrait of depression and suicide. It crushes you when, at the end, the singer reveals his relief that it was his mother, and not himself, who was mad.

Until recently I was convinced it was an absolutely accurate account of Friedman's relationship with his own mother; a little internet digging has almost convinced me he was employing creative license. In any case, Dean Friedman wrote and sang the saddest song I know.

[Video not showing above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/814mother]

WHY SO SAD?

Why we like sad songs is not a mystery; some people will say with certainty that when we experience loss in real life — or empathize with the pain of others — certain hormones are released within us to help us cope with the pain. Chief among these are prolactin and oxytocin, which help us cope by making us feel consoled and supported.

When you listen to a sad song, you might experience the release of these hormones. Some people believe that you do, but the hard evidence is, as usual, inconclusive. Some studies have found no evidence that sad songs trigger the release of these hormones; others have found that they do.

What I suspect is that people are different; some of us get a little shot of these hormones when we hear sad songs, others don't. Some people might not even think "Song for My Mother" is really a sad song. I suppose they might think it over-baked and histrionic. I know a famous music critic whose work I greatly respect who thinks Lucinda Williams' "Car Wheels (On a Gravel Road)" — another song that's both very sad and very good — is inauthentic schmaltz.

People can disagree about these things; your body will tell you what you believe. Some people probably get dosed with prolactin and oxytocin when they hear Bobby Goldsboro's "Honey," which strikes me as mawkish and manipulative. On the other hand, I can tear up listening to Jackson Browne's "Late for the Sky." Even though I don't necessarily disagree with the characterization of Browne as Keith Partridge with a thesaurus, it would be dishonest to deny the power that record had (and has) for me.

I've turned to it a couple of times in life. And there was also a night long ago when I listened to Robert Johnson's "Love in Vain" on repeat, the indicators on the stereo glowing in parody of the lyric "the blue light was my baby, and the red light was my mind."

And another night I drove around the hills north of Scottsdale, Ariz., feeling lonely and listening to, of all things, Bruce Springsteen's "Lucky Town" album, an upbeat record that's sad only when viewed in the context of how it was received upon release. A lot of Springsteen fans consider it one of his worst; some complained it was "too happy." When Springsteen was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999, he alluded to the record.

"I tried [writing happy songs] in the early '90s and it didn't work," he said. "The public didn't like it."

I can't play "Lucky Town" today. It would make me cry. For reasons that are none of your business.

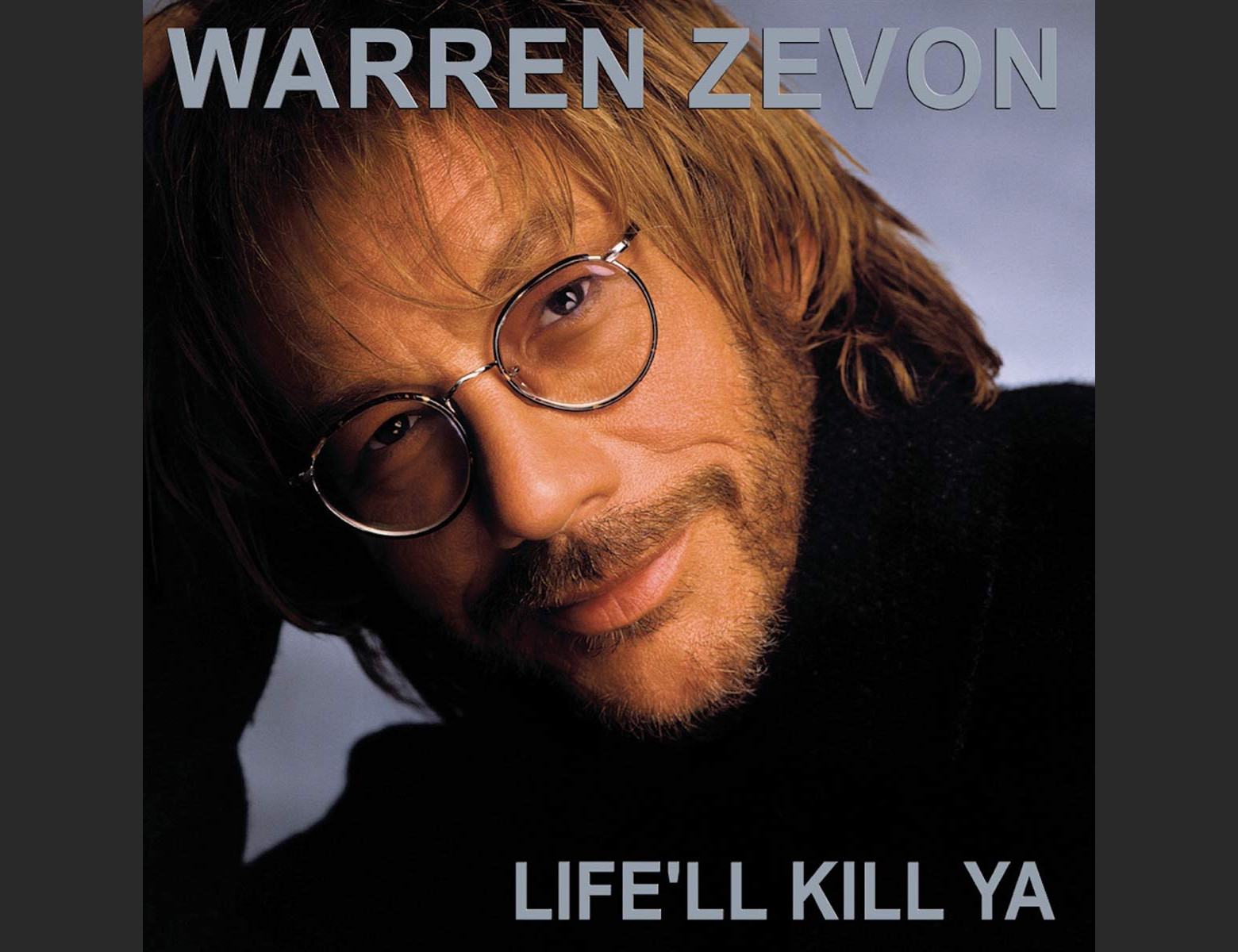

Memorable sad songs include the Warren Zevon’s song “Don’t Let Us Get Sick” from his “Life’ll Kill Ya” album — a song made the more poignant as he was sick at the time he recorded it. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) PAIN EXCHANGE

Memorable sad songs include the Warren Zevon’s song “Don’t Let Us Get Sick” from his “Life’ll Kill Ya” album — a song made the more poignant as he was sick at the time he recorded it. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) PAIN EXCHANGE

Disappointment may be a uniquely human experience; we may be the only animals with a capacity for hope and dread. Small birds hop around dead mates, oblivious, their small hard eyes impervious to sorrow. Bears don't get cryptic texts from other bears. People are the vulnerable beasts.

We can wound each other with our eyes. We can ghost our friends. We can selfishly shut it down.

I think we all need fallback positions, habits of despair like sad songs and soapy movies. You're not grown up until you've felt both the heart-seizing clutch of love revoked and the tender attentions of love returned. You have to die a little to make yourself ready for beauty and grace, you can't understand what those things are until you've felt loss. Yin and yang stuff.

There's a sanskrit term, kama muta, that invokes the sudden feeling of connectedness with the cosmos or another person. It's not exactly the same feeling as love, but love adjacent, the feeling of being moved. Hearing a sad song can induce this feeling because it reminds us we are not alone in the world. In Warren Zevon's song "Don't Let Us Get Sick" — a song made all the more poignant as he was sick at the time he recorded it — he includes this verse:

- The sky was on fire when I walked to the mill

- To take up some slack in the line

- And I thought of my friends, and the troubles they've had

- To keep me from thinking of mine

I hear that and experience is kama muta, the sense that we're all in this together. We are capable of being moved by another's experience because we recognize we are all pretty much the same. Even down to the tiny bit of sardonic self-effacing wit Zevon injects into the song. Yes, he's holding up his end, but part of the reason he's being a good neighbor is because it distracts him from whatever private torment he's feeling.

We are connected by our pain.

We are a community of sufferers, and we are comforted by the knowledge that others have felt what we've felt. A sad song induces empathy as we consider the emotional state of the singer. Part of what makes Zevon's unmistakably prayerful "Don't Let Us Get Sick" so relatable is the offhand manner with which he delivers his lines and the masculine American stoicism propping the whole thing up.

"Don't Let Us Get Sick" is the kind of prayer you could imagine John Wayne or Steve McQueen or Clint Eastwood offering up, until we arrive at the penultimate verse and Zevon (nearly) bares his soul:

- The moon has a face

- And it smiles on the lake

- And it causes the ripples in Time

- I'm lucky to be here,

- With someone I like

- Who maketh my spirit to shine

Notice the withholding of "like" — not "love," though we understand that what the singer is describing is love — and the almost self-mocking introduction of what could be called "poetic" language in the final line. "Who maketh my spirit to shine" is not anything anyone would say seriously; it's a private joke and like all good jokes it only works because it's true.

"Don't Let Us Get Sick" is a sad song because it reminds us of our mortality, but it's also an uplifting song that reminds us of the possibility of finding — and keeping, for a while — happiness.

Maybe prolactin and oxytocin have something to do with that.

[Video not showing above? Click here to watch: arkansasonline.com/814sick]

A sad song is a little like a horror movie — a safe place to experience extreme emotion. I've never been a soldier, and Richard Thompson hasn't either, but I don't know that there's ever been a better three-and-a-half minute anti-war statement than his 1986 song "How Will I Ever Be Simple Again," which seems to be about an occupying soldier's encounter with a young girl:

- Oh she danced in the street with the guns all around her

- All torn like a rag doll, barefoot in the rain

- And she sang like a child, toora-day, toora-daddy

- Oh how will I ever be simple again?

The power of the song derives from what's unsaid. We don't know about the war, who is fighting who where or for what, or even whether the soldier is that much older than the girl who, after all, "is like a child," which suggests she's not a child. And he's intimate enough with her to sit at her table and to know her hair smells "like cornfields in May."

There's a sense the land's been poisoned, there's "nothing but fever and ghosts in the water," and this battle-hardened soldier is moved by her plight, but when was he ever simple, exactly? Or is she singing for herself?

I learned to play "How Will I Ever Be Simple Again" on guitar but can rarely get through it without choking up, which is silly and self-regarding because after all it's about two imaginary people made up by a British folk singer. I always associated it with the Chernobyl disaster, but if you look it up you find that the album it was on, "Daring Adventures," came out a month before the reactors melted down.

Paul Westerberg recorded two versions of “Crackle and Drag,” a sad song about the suicide of Sylvia Plath. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) GO DIRECTLY TO SADNESS

Paul Westerberg recorded two versions of “Crackle and Drag,” a sad song about the suicide of Sylvia Plath. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) GO DIRECTLY TO SADNESS

Some sad songs are more direct — if you've ever lost someone to suicide, Frank Turner's "Song for Josh" will likely gut-punch you. Paul Westerberg recorded two versions of "Crackle and Drag," about the suicide of Sylvia Plath, a snotty, sloppy punk breakdown and an eerie, haunting acoustic version that, as much as Westerberg might protest, approaches genuine poetry.

Grief is a luxury we should understand that many people cannot access because they lack the financial or emotional resources.

To aspire to pop artistry is to strive for the inchoate universal — to connect with as large and diverse an audience as possible. But we each have our own private theaters in our heads, and some things play there better than others. You never experience anything in a vacuum, you can't escape your own experience and prejudice, the calibrated discernment we call taste. And we probably shouldn't think too much about these things.

People who think a lot about art run the risk of shutting down certain avenues of delight. That's the whole thrust of Susan Sontag's old argument "Against Interpretation" as well as the general condition of deconstructionists — who disbelieve in meaning — and art snobs. Sometimes we need to let ourselves be affected, to feel the biochemical washes produced by intense seeing, hearing and touching. The danger of being too analytical begins to see around the sides of things, to deflect intuition and notice only the mechanical things — the way the camera moves or the mathematics of a guitar solo.

You've got to allow for the moment, for the circumstances, for what Jung called synchronicity. And when something happens you've got to give in to it, to laugh if that's what's called for, or to weep. It is always easier to sit on your hands and smile the bemused smile of the cynic.

If a Bob Dylan or a Bertolucci moves you, good. It is good to be wracked with grief, good to be exhilarated in the presence of beauty. It is good to hear sad songs and to respond to them, to feel the devil lurking in the corners of your heart because, you know, he's there whether you acknowledge him or not.

Email: [email protected]