Arkansas' criminal eviction statute, the only one of its kind in the nation, is facing its third challenge in federal court.

Eviction for failure to pay rent is a civil matter in all other states, but in Arkansas, the law states that anyone behind on rent "shall at once forfeit all right to longer occupy" the rented space, allowing tenants to be charged with a misdemeanor and fined up to $25 per day if they don't leave the property within 10 days of notice.

The criminal statute "terminates the rest of the lease" if a tenant is behind on rent by just one day, said Lynn Foster, president of Arkansans for Stronger Communities and a former law professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. It has been used to arrest more than 300 Arkansans in the past decade, according to state data.

Cynthia and Terry Easley of Malvern filed a lawsuit Sept. 2 in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, challenging the "failure to vacate" law.

[ARRESTS: Chart of arrests by year not appearing above? Click here » arkansasonline.com/912arrests/]

The Easleys fell behind on rent in August 2020 after a broken water tank left them without running water, according to a news release from Equal Justice Under Law. The expenses accrued buying water and renting a portable toilet prevented them from paying rent, which was waived for only a month, the release states.

They received an eviction notice in April, ordering them to move out in 10 days or be criminally charged.

Since 2011, 324 tenants have been arrested under the failure-to-vacate statute, according to the Arkansas Crime Information Center.

However, Foster said landlords' use of eviction notices before filing charges means more tenants are affected by the law than are represented in arrest data.

"In practice, landlords use this law to force tenants to self-evict," the news release states. "This strategy is effective, as tenants will abandon their homes to avoid the possibility of criminal prosecution, even if they have legitimate reasons why rent is late or even if the landlord is lying about rent owed. If tenants go to court, they are not given an opportunity to explain but instead told to move out or go to jail for contempt of court."

All 75 counties in Arkansas, as well as the 49 other states, have civil eviction laws. Tenants do not face potential imprisonment in civil eviction cases. Additionally, the landlord is the plaintiff in a civil eviction proceeding and must pay court costs, while tenants must pay court fees if they choose to challenge a criminal eviction.

A number of Arkansas district courts have found the criminal eviction law unconstitutional, including Pulaski County in 2015. Artoria Smith, a tenant in Little Rock, did not comply with a notice of eviction and was convicted of a misdemeanor in Pulaski County Circuit Court.

She appealed the conviction, and the county district court overturned it, saying the failure-to vacate statute violated a tenant's constitutional right to due process.

Circuit courts in Craighead, Poinsett and Woodruff counties all have made similar rulings since. The number of failure-to-vacate arrests per year has not exceeded 30 since 2014, when it peaked at 70, according to the data from the past decade.

Application of the law varies throughout the state, depending on whether landlords are willing to use it, whether lawyers are willing to prosecute the cases and whether judges are willing to hear them, said Jason Auer, an attorney and housing work group leader with Legal Aid of Arkansas.

The counties that still hear failure-to-vacate cases, according to court data, include Garland, Miller, Pope, Scott, Lonoke and, in the Easleys' case, Hot Spring.

"A lot of prosecutors don't like this law," Auer said. "They think it's unconstitutional or a waste of their time, and a lot of judges don't like the law either."

Auer worked on a previous challenge of this law in federal court that was dismissed on procedural grounds in 2017. The criminal case against the tenant, Mitchell Purdom of Mountain Home, was dismissed, and a federal judge dismissed the federal challenge a year later because Purdom "was no longer under threat of being prosecuted," Auer said.

Additionally, the Arkansas Legislature amended the failure-to-vacate law to remove the threat of jail time, so the circumstances Purdom's case opposed had changed, Auer said.

Another tenant who faced eviction after losing his job during the coronavirus pandemic challenged the failure-to-vacate law in federal court again last year. The case was dismissed within weeks because the tenant, Edrin Allen of McGehee, also was no longer under threat of prosecution.

"You're talking about a low-level misdemeanor that a lot of people liken to a traffic ticket in terms of prosecution, and nobody is going to want to keep the threat of prosecution alive as long as there's one individual defendant," said Amy Pritchard, a UALR law professor at the Bowen Legal Clinic.

The Bowen Legal Clinic and legal nonprofit Equal Justice Under Law are representing the Easleys in the current case.

To avoid having another case tossed before a ruling on the constitutionality of the law, the Easleys' lawyers hope to keep the case alive as long as possible, looking for more plaintiffs to form a class-action suit, Pritchard said. Plaintiffs can remain parties to class-actions suits even if their individual cases are resolved.

Anyone who has been affected by the failure-to-vacate law anywhere in the state since Sept. 2, the day the suit was filed, is eligible to join the class of plaintiffs, said Natasha Baker, a staff attorney with Equal Justice Under Law.

The Landlords' Association of Arkansas did not respond to requests for comment last week about the use of the criminal eviction statute or the legal challenge against it. The Arkansas Realtors' Association declined to comment.

However, the complaint filed in the Easleys' suit included a quote from Steve Webster, president of the Hot Springs Landlord Association, who told news outlet ProPublica in 2020 that landlords apply the statute as "a simple, easy to use law that's inexpensive."

The federal government placed a moratorium on most evictions in 2020 because of the pandemic. After several extensions, the moratorium ended in August.

Pritchard said she expects to see an uptick in criminal charges for failure to vacate now that the moratorium is over, especially because it costs landlords very little time and money.

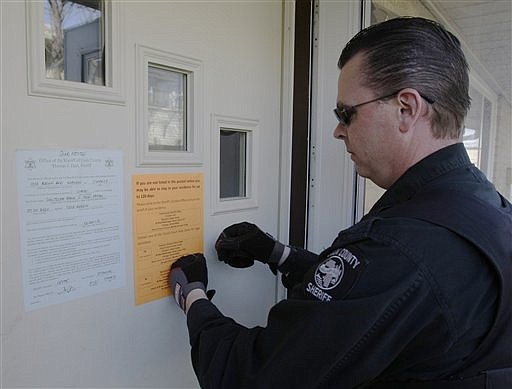

"A lot of landlords didn't realize it was a criminal prosecution," Pritchard said. "They just knew that they could go to the sheriff's office, fill out an affidavit and let the government take care of it."