Sabine Schmidt and Don House grew up a world apart -- literally. House was the son of a career soldier, so his family moved every three years, and his childhood included homes in California, Austria, Germany, Texas, Michigan and Missouri. Schmidt was born in Wiesbaden, in what was then West Germany, and spent much of her childhood in a small town a few miles away.

But there were parallels that are still reflected in their lives today. Both are photographers, known for their collaborations of House's intimate black-and-white portraits of people and Schmidt's immersive color photos of the structures where those people live and work.

And both, Schmidt says, are lifelong library users.

"Like so many people, we grew up going to libraries in our hometowns and have spent much time in them as adults," Schmidt says. "While we love the Fayetteville Public Library with its world-class spaces, collections and services, we started spending more time in the St. Paul [Public] Library in Madison County. It's 25 miles from where we live to each one, but in opposite directions.

"We wanted to support the small, rural, under-resourced library," Schmidt says. "Circulation numbers are so important, so I wanted to do my part. ... It may be easier to just browse and pick things from the amazing collection at the Fayetteville Public Library, and I did that for many years when I lived within walking distance. But it still feels like FPL didn't need my support as much as St. Paul. Also, there's no shortage of interesting people and stories in St. Paul, and it's impossible to avoid either when you're in the library."

"I think a good metaphor might be needing a tool and going to a big box store like Lowe's, or a small hardware store like Johnson's in Fayetteville," House muses. "When you're done, you'll have the tool you need either way, but the experience is significantly different. I prefer the personal attention, the knowledgeable staff, the controlled social interaction of the smaller store. I get to see the woman behind the curtain, so to speak. And smaller libraries are able to offer everything their larger versions offer through interlibrary loan. To continue the metaphor, I can't wait to get out of the big box, but I leave the small store almost reluctantly. What all libraries have in common, of course, are librarians; that is the key."

Of course, the idea for a project together evolved from these musings.

"We chose 21 libraries that serve no more than 2,500 people, with exceptions, such as Eureka Springs and Charleston," Schmidt says. "We easily could have photographed 21 or 42 more; there are about 230 public libraries in Arkansas, and they all do amazing work. We visited about 50 total on our trips around the state, but we were limited by financial and logistical concerns. The project took three years. At some point we realized that the photos were not enough to tell all the stories we heard and things we learned, so we each wrote one essay per library plus a prologue and epilogue."

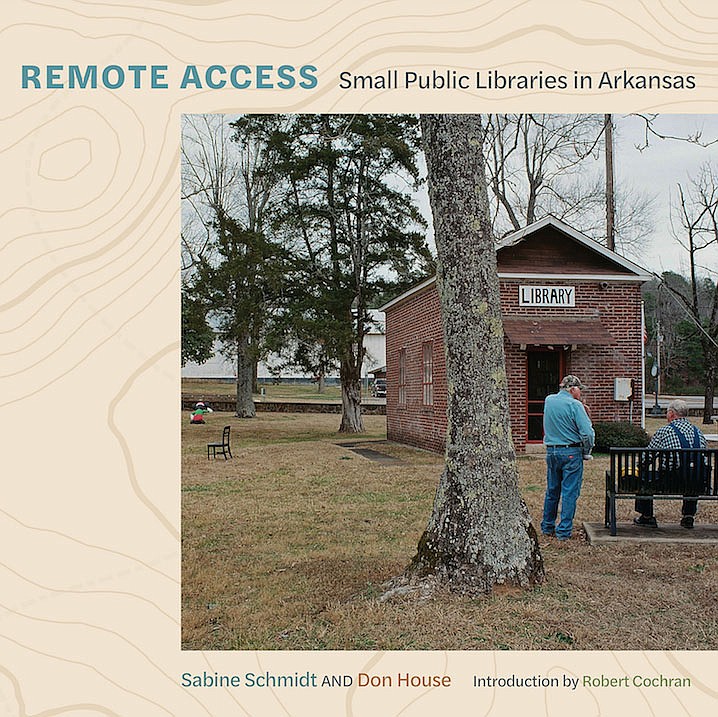

An event at 6 p.m. today at the Pryor Center in Fayetteville will mark the official release of the result, "Remote Access: Small Public Libraries in Arkansas," 360 pages, 400 photos, 44 essays, an introduction by Dr. Robert Cochran, director of the Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies at the University of Arkansas -- "and, we hope, a celebration of an indispensable civic institution," says Schmidt.

House and Schmidt agreed to answer a few questions about the book for the Our Town section -- and Schmidt says they did it the same way they wrote the essays in the book, "not sharing ideas or drafts until we felt they were ready to be seen by the other. This approach led to a lot of surprising parallels and agreements, which also turned out to be true here."

Q. How did libraries influence your childhood?

House: I learned to read in school, of course, but it was libraries that made it clear why I needed to read. Reading allowed me access to the treasures in those often small, but to me, astounding collections of books. And they offered a refuge from family and school pressures. While childhood interactions with libraries were critical to how I saw the world, and who I became, that influence continued into adulthood, and to this day I still rely on libraries. Nothing has changed except I can now reach the upper shelves by myself.

Schmidt: Our town had a small, one-room public library that was open one afternoon a week. It was run by a picture-book librarian, a kindly, gray-haired woman who let me read pretty much whatever I wanted but gently guided me away from the books I really wasn't ready for. I usually carried a library book when I went to the woods. I also read late into the night with a flashlight under the covers. I have a feeling my parents knew that but didn't stop me. The small-town library and the small-town librarian definitely helped shape my reading habits.

Q. How did the idea for the book come about? What did you hope to accomplish?

House: I wanted to highlight the role that libraries play, especially in smaller communities, and to honor the librarians and volunteers who make the magic happen, using the only tools I have available -- camera and pen. I knew the story could be best told if it were a collaboration with Sabine. I had already seen her powerful work, and how it could mesh with mine, and it turned out that she was developing her own ideas about the critical nature of libraries. We met and talked about possible approaches and brainstormed ideas, but the best idea we had was to make a phone call to Dr. Robert Cochran of the Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies at the University of Arkansas. He had written extensively about Arkansas culture, and had edited the Arkansas Character series that included "An Arkansas Florilegium" by Edwin Smith and Kent Bonar and "True Faith, True Light" by Kelly Mulhollan. His suggestions and his interest in fitting our project into his book series, his moral and financial support, made all the difference. We left with a plan of action and enough enthusiasm to carry us through three years of work. A few months after that conversation we presented a sample chapter to Mike Bieker, the director of the UA Press, and his generous commitment to produce a book in the series cemented the project and allowed us to continue with a definite end game deadline in mind -- something that I find useful in forcing me to stay on task, so to speak.

Schmidt: It was Don's idea. He wanted to show the people in those small libraries and tell their stories through his photos. Don's portrait photography respects and honors the humanity of everyone who sits on the chair he puts on the back drop, and it seemed to me that his deep understanding of people would show everyone's individual character while also creating an encyclopedia of Arkansas faces. I am interested in the "faces" of communities and photograph buildings, streets, empty lots, places that don't get much attention but hold someone's stories and memories. The combination of his visual approach and mine seemed perfect for a project about libraries and their communities. And while we didn't initially plan to include personal essays, our writing styles and points of view also complemented each other well.

Q. Once you started visiting libraries, what were the common denominators that made them vital to their communities?

House: Librarians, pure and simple. When librarians work to find out what their communities need, and how to fulfill those needs, the libraries are vital, in every sense of the word, and in my experience, it is a rare librarian indeed who doesn't do just that.

Schmidt: Driving into a small town and spotting the library sign on a building says "this town is still alive" to me. Here in Northwest Arkansas, it's getting easy to forget the extent to which poverty, racism and economic disadvantage affect much of the rest of the state. A public library serves as a community hub, the place to find information, entertainment and countless other resources, especially in towns that no longer have schools.

Q. Sometimes libraries are dismissed as "just books" and "no one reads anymore." What did you find libraries offer in addition to books? And how important are books in a rural environment?

House: First, the notion that nobody reads anymore is pure fiction. Ask any librarian. But, in addition, libraries offer musical CDs, film DVDs, tools, telescopes, research services, access to the internet -- something critical in the rural environment (the belief that every Arkansas has a cellphone or computer and 24-hour internet access is also pure fiction), email, help with job applications, access to information on social services available in the community, a safe refuge and like wilderness areas, a place to recharge.

Schmidt: People who say that usually haven't set foot in a library in years. If they did, they would immediately understand the importance of the public library as a deeply democratic civic institution, one of the last places where anyone can go and use the services for free. For many libraries, lending books is not their main purpose. People need books, but they also need computer help, assistance with job applications or tax forms, tutoring, child care and learning all sorts of skills. They may be looking for a safe haven, a place to study, a place to access the internet or a place to be creative. They need food and directions to the free clinic or the homeless shelter. What they don't need are short-sighted political leaders who don't have a library card and refuse to understand what libraries do. The role of the library as community anchor is amplified in rural areas where social services often don't exist or are far away. Books are as important in a rural environment as anywhere else, but there is a stronger emphasis on physical books and on DVDs because of the lack of internet and cell phone connectivity.

Q. What do you hope your book does for rural libraries and the people who use them?

House: I hope it reminds the communities and the people in charge of funding decisions of the treasures they have. In one Northwest Arkansas community we visited, not a single member of the city council who determined library funding even had a library card. Library hours are often being reduced and funding curtailed at the worst possible time. We also hope it reminds people in the areas of Arkansas with the greatest resources -- the northwest and Pulaski County -- that huge portions of the state are hurting financially and struggling to do the work that needs doing. And I hope it honors the librarians, one and all, who fight the good fight everyday, day in and day out.

Schmidt: Most importantly, I hope that librarians and patrons recognize themselves in the faces of their counterparts across the state. A sense of togetherness, of shared interests and needs. Rural librarians can feel isolated and find it hard to network and engage in professional development. Our book shows that they are not alone.

Go & Do

Book Launch: ‘Remote Access’

When: 6 p.m. today

Where: Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral & Visual History on the Fayetteville square

Cost: Admission is free

Information: uapress.com

Bonus: The event will also be streamed live on the Pryor Center’s Facebook page at facebook.com/pryorcenter.