Right off the bat, it's important to Celina Coleman that you know she takes full responsibility for the crimes that landed her in the Benton County Jail, where she speaks to a reporter via a rather complicated phone system that requires depositing money into an online account. The phone calls are limited to 15 minutes, after which the call is abruptly cut off. Five 15-minute phone calls cost just under $30 to conduct. Emailing Coleman costs money too, and she has to pay to read and reply to any email correspondence she receives. It's a daunting process for a reporter who is speaking to an inmate for the first time -- and an expensive one, especially for those already struggling with poverty prior to being incarcerated. But, for Coleman, who has been in and out of the system since 2015, it's old hat.

"The whole thing is pretty traumatic, getting used to the processes that the prisons and jails put you through," she acknowledges. "You have to learn how to engage with people. Because you never know who you're going to come across. I'm not going to say that there are bad people in jail, but the things that they've gone through have may have hardened them, so they react in a certain way."

Coleman's voice is calm and level as she walks through the past six years of her life: When she was 19, she was arrested for forging checks. After serving her time, she was jailed several more times for not complying with the terms of her parole -- usually because it was difficult to find a job with a felony on her record, and she struggled to keep up with the fines and fees she was required to pay after release. Then, in 2018, she forged checks again -- and that crime landed her in the Wrightsville Unit of the Arkansas Department of Correction. Coleman is blunt about her past, and she makes no excuses for herself. She will be released at the end of May and, this time, she says, she'll be out of the system for good.

One thing giving her this confidence is her artwork. For Coleman, art has always been a salvation, an outlet that takes her mind off of troubled times and rocky waters, and she hopes to utilize that skill and passion in a career in art therapy once she's out. Her great-grandmother Faye, a veteran of the War Eagle Craft Fair, was the first person who fostered Coleman's urge to create by paying for her to receive a year's worth of instruction from a local artist when Coleman was 7. Coleman soon discovered drawing was a way to both express and manage her emotions.

"I had a good childhood, but it wasn't the best," she says hesitantly. "I'm sure there are worse childhoods out there. But family fights, things like that -- my art was more of an escape for me. It was a comfort zone. I love the colors. I love making my own little world, if that makes sense. And so I kind of dove deep into that. Every piece of art that I've done has a piece of me in it. So they're all kind of like a mini-story."

When Coleman was in high school, things got really rocky: Her father, with whom she was close, was sentenced to serve time in prison. Later that same year, the family home burned down, destroying the bulk of Coleman's artwork. Disheartened, she fell out of the habit of using her art to help her heal and, instead, turned to school sports. After graduation, Coleman attended a Kansas community college to play volleyball. While her life might have seemed like it was on track, it wasn't. She was still wrestling with family-related pain and dropped out of school to move back home. Struggling financially, she forged checks on her father's account. When he found out, he called the police. Though he later refused to press charges, the state did. When Coleman participated in a mural project while serving time in a Regional Punishment Facility program, she was reminded of how much art influenced her mental health.

"I connected with other women there, as well," Coleman says. "They would ask me to do personalized birthday cards, portraits of their family members, to send home more of a personal touch for people."

Once released, Coleman tried to get her life back on track. With a felony on her record now, both employment and housing became infinitely more difficult to obtain. Fines and fees -- like the $35 per month probation fees -- piled up and went unpaid, landing her back in jail a few times as a result. She also owed restitution for the checks she had forged. Then, in 2018, she found out she was pregnant.

"I didn't know what to do; I hadn't really continued to stabilize myself financially," she says. "I was trying to pay fines and fees and couldn't catch up. And I ended up forging checks again. And that sent me down to Wrightsville prison."

Coleman's experience is not unique -- a 2012 Arkansas Department of Corrections report found that the recidivism rate of Arkansas inmates is nearly 52 percent. Coleman says she had a strong friend and family support circle, but that wasn't enough to help her avoid the common pitfalls faced by those recently released from imprisonment. And this time, with an unborn child in the mix, the stakes were higher. She was jailed for much of the pregnancy, awaiting trial, and was eight months pregnant when sentenced to Wrightsville. She was able to see the baby for 24 hours after giving birth in a hospital, shackled to the bed.

"It's not something that I would ever wish on anybody," she says. "You know, people make mistakes. But for a woman to ever go through that, it's very hard."

The next time she saw her baby was around six weeks later, in the visiting room of Wrightsville.

"When I sat down and held her, she just stared at me," remembers Coleman. "And my mom kind of looked at me and started crying. And she told me that it was like my daughter was trying to memorize my face. One of my biggest fears is that she wasn't going to recognize me or know who I was just because of her being taken from me 24 hours after giving birth to her. But it was like she knew me automatically. She was comfortable. She didn't even cry. She giggled, she smiled. She fell asleep in my arms. It really eased my mind and my heart with everything."

With her daughter safe with her mother while she was locked up, Coleman tried to make the most of her time at Wrightsville.

"That was also where my art came into play," she recalls. "I met a woman who had a newborn baby, as well, and we became really close. She didn't have a picture of her husband and her child together, so she showed me a picture of her babies and her husband, and I ended up drawing a portrait of them together, where he was holding her baby in his arms. And then she was able to look at that every day. That became a kind of healing process for me. I wasn't the only woman pregnant in there. And it could have been worse -- my baby could have been taken from me, could have been put in DHS. Not everyone has a family member who is willing and able to take on the responsibility of a newborn."

She was released on Dec. 8, 2019 -- but the system wasn't finished with her yet. She says she still had an outstanding court case in Benton County, where she passed one of the three forged checks she was arrested for. Washington and Pulaski counties agreed to have her sentences run concurrently, Benton County did not. So instead of going home on Dec. 8, she was picked up by transport for Benton County and taken to the Benton County Jail.

"My grandmother actually bailed me out so I could spend my first Christmas with my daughter, for our first Christmas together," says Coleman. "It's something that I struggled with. I did the crime, I'm owning up to it, I'm going to do what I need to do to get past it, to reconcile with my victim, things of that sort. But at the same time, it's just -- how much more are you going to take away from me? Even though I'm trying to battle and get through all this? The emotional turmoil, it just kind of snowballs a little bit sometimes."

Her case spent the next year-and-a-half winding its way through the court system. Her case spent the next year-and-a-half winding its way through the court system, and Coleman was determined to make the most of that time. She had a place to live, eventually got a job with the Taco Bell corporation and was able to start moving up the ladder there. She made plans to go back to school to pursue an art therapy career. Her hope was to get financially stable enough to take back custody of her daughter. When Benton County approached her with a deal for 120 days in the Benton County Jail -- a significant reduction from the eight years she says they were pushing for at first -- she took it.

When she went away this time, Coleman at least knew what to expect. That doesn't make it any easier, she says.

"I can say for nearly all of the people who have been or are incarcerated, that time and space is a huge battle to face while incarcerated," she wrote from the Benton County jail. "Time never ceases for anyone. We do the crime, we know we do the time in here. That's something we all accept. With that being said, people come in and out so often. It's a constant reminder of the amount of life we are spending due to our mistake. A lot of us have children and, of course, families that we are anxious to get home to. When it comes to space, there is little of it. You can pretty much compare it to seeing hamsters at a PetSmart. Some of us are pacing in an open area, others are trying to sleep, and the rest are in a daze. The noise is like a food court in a shopping mall. It doesn't stop. Everyone has a different mentality, that includes morals and values. It's a mixing pot in here. Due to the circumstances, someone can do something that annoys you or insults you, and you have the choice to act out on it or sit with it. Every move you make is vital and more often than not ... you're required to build tolerance. It's a humbling process if you develop the patience for it."

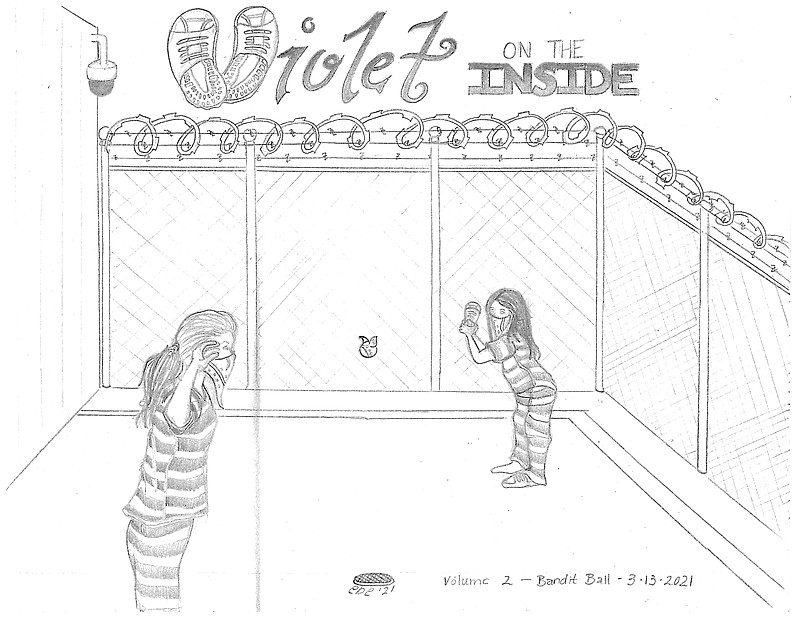

For Coleman, using her art as a diversion helps her with the patience part.

"It's more for comic relief," she says. "Because there's no getting away from the room that you're in. You can't go outside, you can't get away from the constant chitchat. Women are talking 24/7. It's just nonstop."

Release will offer a slate of challenges with which she's familiar and which have felled her once before. She estimates she'll owe somewhere in the neighborhood of $2,000 in fees and fines, not including the $35 per month charge for probation. Being incarcerated is an expensive business, with the burden falling on people who, often, are low-income to start out with. Fees can pile up quickly -- for example, while inside, visits to the nurse cost $20, and if medicine is prescribed, inmates must pay $5 per pill administered. Any fees remaining on the inmate's account are rolled into the fees owed at the end of the sentence. Coleman's success post-sentencing is dependent on whether she's able to get a decent paying job that will allow her to keep up with the monthly payments she has to make in order to be in compliance with her parole.

For her part, Coleman is optimistic about the future -- a place she got to only by looking at her past as a difficult learning process.

"I do wholeheartedly, because I wouldn't be the person that I am today if he had not," she says when asked if she forgives her father for turning her in for her first infraction. "I wouldn't even have my daughter if things would have gone differently. I'm thankful for it because it's put me in a lot of situations where I've learned a lot. Certainly had some hard outcomes, but I wouldn't change any of it. So I definitely forgive him. Because I know that good-hearted people make mistakes all the time. It's not only bad people who make mistakes. It's good-hearted people, whether they get caught or not.

"I had to learn how to love myself, to become comfortable in my own skin, even through the most difficult times. We're all perfectly imperfect. Pain that isn't transformed gets transmitted through generational movement. I want my daughter to grow up knowing that it's OK to make mistakes. It's about how you get back up and move forward. We all have a story to tell, and we would all learn that we have more in common with one another if we became more vulnerable and open."

Ultimately, she says, she hopes what she's learned will help make her better at her chosen career path -- art therapy.

"Being in here, seeing all different walks of life and the people and the things that they go through, I can honestly say I have met the most loyal people in jail and prison," she says. "When you connect with people in here, and you hear what they've gone through, it becomes easier and more necessary to see them in a different light."