Many a Black child in the segregated South owed their education, at least in part, to a man named Julius Rosenwald.

The clothier-turned-Sears, Roebuck and Co. investor-turned Sears president and chairman was also a philanthropist who served as a trustee of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. A friend to Booker T. Washington, Rosenwald established a self-named fund in 1917 ... a fund "aimed ... specifically at creating more equitable opportunities for African-Americans," according to information from the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program.

Through the fund, Rosenwald built rural schools attended by Black children from the 1910s into the early 1930s — more than 5,300 school buildings in Black communities throughout 15 southern states, reveals the website historysouth.org, with the hosting communities pitching in money and labor for the schools.

Originally, 389 of these Rosenwald buildings — which included not just the schools themselves but also shops and teacher's houses — were erected in Arkansas.

In 2005, Ralph S. Wilcox, National Register and survey coordinator for the Historic Preservation Program, put together a document on the surviving schools in Arkansas which, at the time, had dwindled to fewer than 20. His involvement with Rosenwald School history began in 2002, the year the National Trust for Historic Preservation put the schools on its annual Most Endangered Properties list. Although some had been put to alternate uses for a time after integration sounded the death knell on their use as all-Black schools, most were vacant or underutilized and had fallen into disrepair, according to the document. (Kwendeche, a Little Rock architect who goes by one name, has been helping with projects that involve preservation of a handful of former Rosenwald schools.)

LONG MEMORIES

The one thing that had continued to thrive ... people's memories of the the schools.

"If I was going to be going to a particular county to see what I could find, our agency often did a press release ahead of time, just so that we could see if there were any local people who had knowledge of these buildings," Wilcox recalls. "We would get calls from people — 'Oh yeah, I used to go to that school and it used to be here,' or 'My mother went to that school,' or that kind of thing."

Of the surviving Rosenwald schools, the largest and most prominent one is still in use in Arkansas' capital city: Dunbar Middle School.

Each school was, and is, "special in its own way," Wilcox notes. "But Dunbar is really an important one because of the fact that it was a junior high school, high school and ... junior college. And the Rosenwald fund only did, I think ... less than five that were that large around the country. So Dunbar was really kind of a unique case."

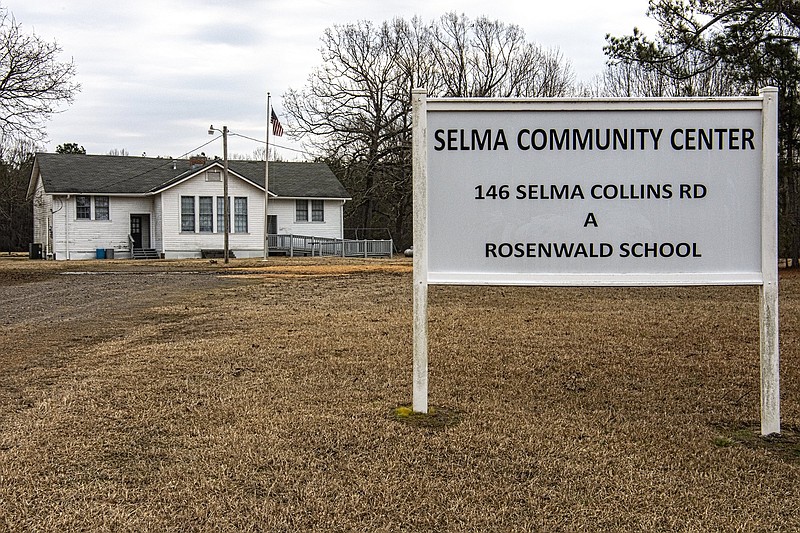

Another standout Rosenwald school in Wilcox's eyes is the Selma Rosenwald School, built in 1925 in Drew County; the school was restored in a project funded by a grant from Lowe's Corp. The renovated school was put into use as a community center.

"A lot of these schools were ... really kind of community centers in their own right ... so the one in Selma is a special one just because it's still serving the community just like it was when it was built," Wilcox adds.

Unfortunately, since Wilcox put that document together, several buildings — including the Tollette Shop Building in Howard County and the Lafayette Shop Building in Ouachita County — have fallen prey to demolition or collapse.

A ROSENWALD TRIO

A Feb. 25 road trip included visits to three of the school sites: the Selma Rosenwald School in Selma, the Chicot County Training School in Dermott and the Mt. Olive Rosenwald School in Mt. Olive (Bradley County).

Indicated by a sign, the renovated Selma School, built in 1925 and placed on the National Register in 2006, lies off Collins Road on an expansive tract of well-tended land. Used at one time as a Masonic lodge, the neat, white building has been restored to its original plan, with the protruding center front of the school — originally designated as the Industrial Room — distinguished by four tall windows in a row and flanked by two side entrances. At one time, two of the Industrial Room's windows had been removed and a central entrance into the room had been made, flanked by shortened versions of the remaining two outer windows. The only evidence of that central entrance: a short set of stairs to nowhere. The building is now equipped with a wheelchair ramp leading to one of its side entrances. The building's surroundings include a swing set with one swing remaining; concrete benches; a picnic pavilion and a scattering of stately old trees.

It's a different story, however, in Dermott. The only thing that remains of the Chicot County Training School building that once stood at Hazel and North School streets is a pile of rubble. Built in 1929, the building had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. At $22,400, it had been among the most expensive schools built during the 1928-29 budget cycle, according to the Historic Preservation Program. Last used as a public school in 1975, the facility was acquired by the Morris Booker Memorial College board and had last served as a Head Start facility before being vacated. Deteriorating, the school succumbed to a "chain-reaction" collapse, followed by a fire last summer. They had wanted to save the building, but "while we were trying to stabilize the back end, the front end fell," says Dermott Mayor Walter Donald. "Matter of fact, it caught on fire twice." Clearing the rubble is a big project that will require funding and equipment not presently on hand, Donald adds.

Donald, who went to Chicot County High School, then transferred and ended up graduating from Morris Booker, hopes the site can eventually be redeveloped.

"We are hoping ... that we can get it and [create] a cultural center for southeast Arkansas and display the history of our people." He envisions a museum and special-event facilities.

He points out a couple of nearby unused buildings that he'd like to see as part of this redevelopment. "This would make a great place for retreats."

LIFE AFTER PEOPLE

Sadly, the school at Mt. Olive, built in 1927 and also placed on the National Register in 2004, is on the verge of joining the Chicot County Training School. Standing in an unkempt setting surrounded by woods, the building is still abandoned, open to explorers, flora and fauna, and in critical disrepair ... missing flooring, missing ceiling boards, a couple of piles of animal excrement, an abundance of abandoned mud dauber wasp tunnels. One can see where the building's once-tall outer windows and interior transom doors had been shortened. A few hanging tiles hark back to the dropped ceiling that had been added later in the school's life, along with dangling remains of the framework for that ceiling.

According to Historic Preservation Program records, the Mt. Olive School functioned as a community center as well as a venue for quilting parties and special events. A lone church pew and a small pulpit suggest the facility's use also as a place for church functions. In several ways, the building seems stuck at moments in time, as though its users were interrupted as they went about their activities. An open, dilapidated book on an old teal corduroy recliner adorns the porch. In the largest room, the seat of an ancient easy chair, its stained upholstery long ruined, contains what looks to be abandoned embroidery projects. An old cardboard box contains musty records that are a nod to the school's onetime role as a community action agency; a notice posted on one wall educates readers of "appeal rights of applicants denied assistance under the energy crisis assistance program."

ROSENWALD, REVISITED

One of the best ways to preserve the legacy of these schools "is just to educate people on what that program was and what the good was that came out of that program," Wilcox says. "Julius Rosenwald saw a definite need for the improvement of African American education, and he worked very closely with Booker T. Washington and Tuskegee Institute to develop the Rosenwald school program.

"When you think about the fact that there were over 5,000 Rosenwald schools built around the country, that's a tremendous number of schools. And [there was] the tremendous monetary investment that Rosenwald put into it and also the time that was involved. And you think about the number of students who benefited from that generosity over the years. It's a tremendous legacy."