CAP-HAITIEN, Haiti -- Heckled by protesters and surrounded by phalanxes of heavily armed guards, foreign diplomats and Haitian politicians attended the funeral of Haiti's assassinated president Friday, a tense event that laid bare a fractured nation's problems instead of providing an opportunity for healing.

Less than a half-hour into the funeral, foreign dignitaries including the U.S. delegation, led by Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, departed over safety concerns because of gunshots reported near the event. White House press secretary Jen Psaki said "the presidential delegation is safe and accounted for in light of the reported shootings outside the funeral" and was heading back to the United States, cutting the visit short.

Earlier, as the flag-covered coffin of President Jovenel Moise was moved onto a central stage lined with white curtains, carried by men in military uniforms, a moment that many had hoped would help promote reconciliation was overshadowed by tensions that had exploded in the streets the day before and carried over into Friday.

A line of Moise's supporters stood by the entrance to the funeral, held at his family homestead, and yelled at arriving politicians: "Justice for Jovenel!"

When Haiti's national police chief, Leon Charles, arrived, the crowd surged around him and broke into shouting and finger-pointing. Cries of "Assassin!" filled the air. As he passed a grandstand of guests, many there also jumped to their feet to holler their displeasure.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » arkansasonline.com/724moise/]

"He killed the president!" shouted Marie Michelle Nelcifor, adding that she believed Moise had called Charles while assassins attacked his home but that Charles had not sent police officers to defend him. "Where were the security guards?" she asked.

"You didn't take any measures to save Jovenel!" one woman yelled. "You contributed to his killing!"

On the grounds below, one Moise supporter threatened Charles: "You need to leave now or we're going to get you after the funeral!"

Others were angry that the president would be buried before the investigation was completed. "They are burying him surrounded by his assassins!" shouted Kettie Compere, a mother of two, looking up at the grandstand of diplomats and Haitian politicians where Charles had settled.

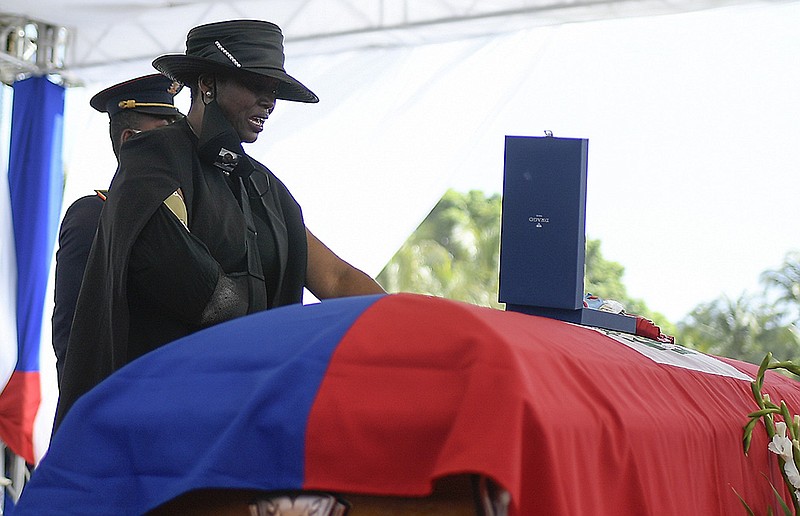

When Martine Moise, the president's widow, arrived wearing a mask with a photo of her husband affixed to it, the crowd surged around her, crying "Justice! Justice!" and singing "Arrest them, arrest them."

Speaking publicly for the first time since the assassination, which also left her wounded, Moise delivered a eulogy that was pointedly political. While telling the mourners that her family is "living in dark days," she implied that her husband had been killed by the country's leading bourgeoisie families.

"Is it a crime to want to free the state from the clutches of the corrupt oligarchs?" she said, standing at the podium with her three children surrounding her.

"The raptors are still running the streets with their bloody claws," she said. "They are still looking for prey. They are not even hiding. They are there watching me and listening to us, hoping to scare me. Their thirst for blood has not been quenched yet."

Her soft voice grew stronger through a 15-minute speech as she thanked the crowd for its support and said those responsible would not assassinate Jovenel Moise's vision, ideas or dreams for Haiti.

"We lost a fight, but we did not lose the war," she said as she suggested that Moise was killed in his pursuit to provide electricity, build roads and make a better life for poor people.

The smell of tear gas wafted over the family compound during the funeral. Afterward, guests returning to the city of Cap-Haitien nearby saw the fresh remnants of burning tires and navigated through streets blocked with felled trees and rocks.

CALL FOR SOLIDARITY

In remarks during the U.S. delegation's arrival at Cap-Haitien's airport earlier Friday, Thomas-Greenfield said: "Our delegation is here to bring a message to the Haitian people: You deserve democracy, stability, security and prosperity, and we stand with you in this time of crisis. So we come here in solidarity with the Haitian people during this difficult time."

The July 7 killing of Moise, 53, in the bedroom of his home near Port-au-Prince, the capital, has plunged the Caribbean nation of 11 million into one of its deepest crises. Officials have blamed a group of Colombian mercenaries, but many questions remain, including who planned the assassination and why no members of his security detail were hurt.

Several members of that security detail have been questioned and taken into custody.

Pressured by Western countries led by the United States, Haiti's other political leaders, jostling for power, have pledged an orderly transition and a democratic process. But it was clear even before the funeral that deep divisions would shape and possibly subvert what many hoped would be a venue for reconciliation.

Just hours earlier, the northern city of Cap-Haitien -- 30 minutes from his family homestead -- had burned with anger and frustration, exposing Haiti's distrust of the elite in the country's less-developed north.

On Thursday, the streets billowed with the black smoke of burning tires, a common form of protest in a country split by geography, wealth and power. Large crowds of demonstrators ran though the narrow colonial streets, chanting, "They killed Jovenel, and the police were there."

"We sent them someone alive; they sent him back a cadaver," screamed Frantz Atole, a 42-year-old mechanic, promising violence. "This country is not going to be silent."

A new government was installed in the capital this week, and its leaders vowed to get to the bottom of the killing and to build consensus among the country's political factions and civic groups.

Ariel Henry, with support from key international diplomats, was installed as prime minister. Designated by Moise, he replaced interim Prime Minister Claude Joseph and has promised to form a provisional government until elections are held.

'PEOPLE ARE AFRAID'

The unrest threatened to turn hopes of consensus into a naive dream.

"The bourgeoisie from Port-au-Prince are responsible. They are the reason for all of this," said Emmanuella Joseph, a 20-year-old student, crying into a face cloth on the side of the road at the tail end of a running protest.

She said the president's killers were outsiders who had long meddled with the country's destiny. "What kind of nation comes and kills a president?"

Cap-Haitien was once the capital of the French colony of St. Domingue, which claimed one of the most brutal slave plantation economies in the world and was later overwhelmed by the world's most successful slave rebellion.

Banners strung across its roads said "Justice for President Jovenel" and "Thank you President Jovenel. You gave your life for the people's fight and it will continue."

Just off the city's main stone square, where rebel leaders were executed more than two centuries ago, mourners lined up Thursday to sign condolence books and light candles before a large photo of the president in a government building.

"We are living in a time that's so fragile," said Maxil Mompremier, standing outside the colonial-era Notre Dame de L'Assomption Cathedral, where Moise's supporters had gathered earlier for a service.

"Nobody understands what happened. A lot of people are afraid."

Hailing from the north of the country, Moise was not well-known in the country's power center of Port-au-Prince when the governing party chose him as its candidate in the 2015 election. He was born in the town of Trou-du-Nord and later began his entrepreneurial career from Port-de-Paix, where he became president of the Chamber of Commerce.

That he was killed far away in Port-au-Prince inflamed old divisions between the north and the country's capital and economic center. It also deepened the rifts between the country's small elite and its destitute majority.

"It comes back incessantly in all the history of Haiti," said Emile Eyma Jr., a historian in Cap-Haitien.

Information for this article was contributed by Catherine Porter of The New York Times; and by Danica Coto, Evens Sanon and Matthew Lee of The Associated Press.