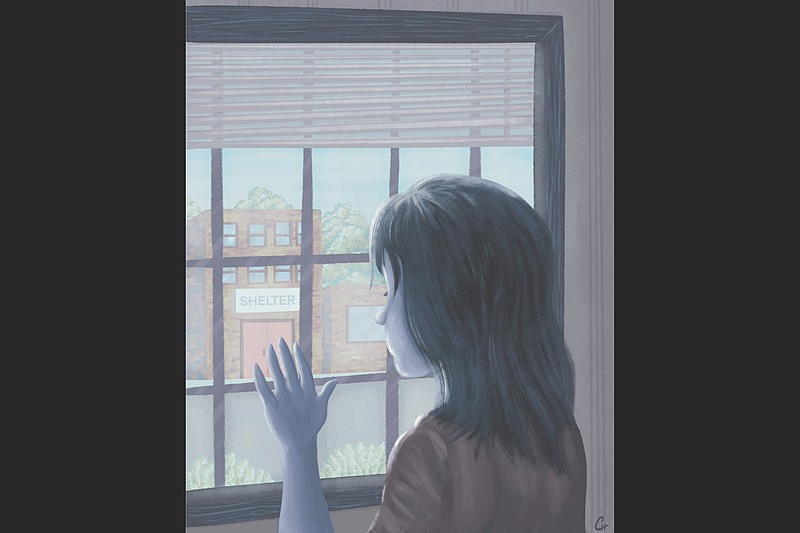

Teresa Mills felt the cold vise of fear grip her insides, tightening with each passing day. It was springtime in Arkansas, well past any chill the weather could hold. But the icy knot was there just the same. Here at the Peace at Home Family Shelter in Fayetteville, one of the largest domestic violence shelters in the state and of which she is chief executive officer, it was too quiet, the hotline too still, the waiting areas and trim sleeping rooms too empty.

"It was very concerning because we knew that the dynamics in relationships that were already strained were not going to improve," Mills says. "I think that we also knew that victims' opportunities to seek services were going to be diminished because they would not have a safe opportunity to reach out. That absolutely concerned us for people's lives."

In every month of the year, the Peace at Home Family Shelter is abuzz with the business of helping domestic abuse survivors decipher the next chapter of their lives. The 55-person occupancy shelter stretches the staff of 35 to make the most of the average 40-45-day stay of its clients, arranging housing, job interviews, medical attention and hope for these hometown refugees.

Then in March, covid-19 threw a bag over the state's head, plunging the shelter into the darkness of unknowing, operating in a halting lurch from one unfamiliar day to the next. From one end of the state to the other, cries for help almost immediately began to fall silent, the sallow faces of survivors toting exhausted children disappearing from shelter doors.

For all the horrors domestic abuse professionals see daily in survivors, nothing scared them like the silence.

"We saw a pretty dramatic decrease in crisis calls between mid-March and mid-May to the first of June," Mills says. "We probably had an average drop of around 70% to 75 % through that period of time. We are one of the largest shelters in the state, we have some of the highest rates of crisis calls per day, and there were days on end when we went without calls. That is very, very unusual for a program of our size.

"There's a — helplessness may not be the right word, but there is a sense of angst over what's going on. It's complicated because we were also, as an organization, as individuals, as employees, as citizens, trying to navigate and figure out what the pandemic meant for all of us individually and collectively as well. It created this dual angst all the way around. It was certainly not a good time."

ABOVE-AVERAGE PROBLEM

Domestic violence is a scourge of almost unimaginable proportions in the United States. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), an average of 20 people per minute are abused by an intimate partner in the United States; 33% of women and 25% of men have experienced abuse in some form. For 25% of women and just over 10% of men, the violence is severe enough to cause hospitalization or post traumatic stress disorder, or drive the victim to seek other outside help. On a typical day in America, shelter hotlines field 20,000 calls.

As the national coalition reports, Arkansas consistently outpaces the national average, with 41% of women and 35% of men experiencing physical violence, sexual violence or stalking by an intimate partner. On one day last year, more than 450 people were served by Arkansas domestic violence shelters, with nearly 40 more requests for service going unmet due to lack of resources.

Most sobering of all: In 2017 The Natural State had the third highest murder rate of women by men. In 2020, 51 people died by domestic violence homicide between January and August, reports the Arkansas Coalition Against Domestic Violence (ACADV) in Little Rock.

"Arkansas has typically remained in the top 10 states for domestic violence homicide for a long, long time," says Beth Goodrich, executive director of the Arkansas coalition. "Going into 2020, [abuse reports] were not going down. I wouldn't say that we were leveling off. There's a slight increase every year and it's like inflation — the more people [that] come to Arkansas, the more people that are born and live here, the more the numbers increase."

Arkansas' 75 counties are served by fewer than half that many shelters. The focus of the coalition, as it headed into 2020, was to better publicize what services were available, Goodrich says. She also wanted to increase law enforcement training for better recognition of signs of domestic abuse.

Instead, the organization found itself agonizing over the knowledge that covid-19 measures were caging many victims with their tormentors, leaving them with no easy way to get help. To Goodrich — who asserts that any statistic on the number of domestic violence victims is, at best, half the actual number — the silence was deafening.

"What happened in 2020 magnified the problems that we already knew were there," she says. "It created lack of access to services for a lot more people. You obviously can't call a hotline with your abuser there at home and even if a shelter offers digital services, which many of them did, you still can't access it if you live with your abuser. In rural areas with lack of internet, it just magnified the problem.

"In addition, it took away one resource that we use a lot, which is a friend or family. If you're worried about covid, you can't go stay with Mom, especially if Mom has health problems or is immunocompromised. It took where we were at and it made it a lot more tenuous. We were all scrambling to figure out how to get our services in front of people who needed them."

FAR-REACHING CONSEQUENCES

Even at shelters with no decrease in calls, the effect of the pandemic was felt.

Vicki Gestring, executive director of Family Crisis Center in Jonesboro notes that, as demand continued unabated, covid-19 restrictions curtailed the shelter's already modest capacity and resources.

"Prior to the pandemic, we could house approximately 16. That's a very full house," she says. "One of the issues that the pandemic created is, we had to reduce our capacity. Some of the shelters put more than one family in a room, and with the pandemic happening, we are not able to do that. So, we have to keep each family in their own room.

"We also saw a decrease in the number of victims that wanted to come into the shelter even after they contacted us," Gestring adds. "It was really heartbreaking because they were put in a position of having to choose between risking the virus in a communal facility or staying at home where the circumstances were dangerous. It was a terrible position for them to be in."

The Jonesboro shelter accommodated survivors as best they could, including renting hotel rooms. But, Gestring says, this isn't a sustainable solution on the organization's budget. As with other shelter leaders, she's fearful for those who cannot reach out even as abuse intensifies.

"Some of our clients who had been here before were more severely abused during covid because they were trapped in the home with their abuser," she says. "Jobs were lost and the financial stress was really bad. Drug and alcohol usage increased, which is just like throwing fuel on a fire when you're in a domestic violence situation."

Gestring, who joined the organization in 1996, has seen a lot of progress in the community's understanding of domestic violence. However, she's quick to admit there's still progress to be made, especially in the rural areas the shelter serves.

"I want people to stop being judgmental about people in domestic-violence situations. I want people to understand that leaving is not a simple act," she says. "One of the most common questions every shelter will tell you people ask is, 'Why do [victims] stay? If this were happening to me, I would take my children and leave.' It is so much more complicated than that.

"There are real circumstances behind what keeps people in a home where this is occurring, what finally makes them leave and, sometimes, what makes them go back."

PRESSURE-COOKER SITUATION

If there's one thing that frightens shelter workers more than the thought of how many people are suffering in silence during the pandemic, it's the prospect of dealing with what many expect will be a tidal wave of pent-up demand once it subsides. Peace at Home in Fayetteville saw hotline call volume creep back to normal by August, then post three straight record-setting months.

"Certainly, our national partners have prepared us for the fact that this is often seen after a national disaster or some sort of major disruption — that you have a big dip and then a huge surge afterwards," Mills says. "We are taking several steps to address this. One of the challenges we had in our current residential space was, we had rooms that shared bathrooms ... That is challenging in terms of social distancing. So, we're adding four bathrooms to our facility to address that.

"We've also built partnerships with local organizations that could do residential services for us. There is an organization that does corporate retreats and they're not really doing those right now, so we've built a relationship with them to be able to house residents."

Women and Children First: The Center Against Family Violence in Little Rock is already tackling capacity concerns by stepping up its transitional housing services.

"Last year, we had 58 families and 58 children who went through our transitional housing program. This year, we've had 174 families and 100 children go through our program," says Angela McGraw, executive director. "That's one of the ways that we've been able to accommodate the need.

"People are really thinking it through now, when they make the decision to leave. For the most part, when they're ready to leave, they're leaving. They're ready to actually transition and get into their own house. We haven't seen that happen before. We've had a lot of people come to the shelter as more of a timeout, a respite-type thing. We're seeing more of them really making that decision to leave."

UNPRECEDENTED SITUATION

Still, McGraw says, the situation is so unprecedented that most shelter officials can only guess at what's going on from rural hollers to gated neighborhoods all over Arkansas ... much less have a firm grasp of what's coming in terms of demand in the new year.

"I still don't think that we have even seen the edge of the domestic violence that has been taking place. I don't think victims have been able to even use their voice to share what's been happening in these homes," she says. "Until our [covid-19] numbers start going down and people feel like they're able to move around a little more, I think there's still a lot happening out there that we don't know about."

Dealing with this largely unknown need is a high-stakes game. Despite best efforts, nearly 2,300 client requests went unmet between August 2019 and March 2020 alone ... a nightmare statistic. Every turning away could mean a death sentence. Such tragic outcomes loom large as shelter leaders brace for what could be a reckoning of stunning proportions in 2021.

"One of the things that we know in this field is, if you can't provide services in your one call, or [don't] have the information right then to get them somewhere else, the likelihood that they're going to get the ability or drive to call back again is really low," Goodrich says. "When you've been a victim of domestic violence, there's so much emotional and mental abuse that has gone into it that, honestly, getting up the strength to make that call can be incredibly difficult.

"Sometimes, people think it's like a switch you turn on and then people have everything they need when they decide to go. That's just not how it works. You can work up the courage for months to make that one call. And if it goes poorly, it perhaps reinforces what their abuser has said, which is that you can't really leave, it's not going to work out and nobody really cares. It reinforces that idea that they're stuck. That's what makes it really hard."