Outspoken judge Wendell Griffen is barred from ever presiding over capital-murder cases, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled Thursday in a decision siding with Attorney General Leslie Rutledge.

The seven-member high court ruled 5-2, with Justice Robin Wynne and Chief Justice Dan Kemp opposing the decision, which was released in an unsigned order, about 2½ months after Rutledge moved to have the Pulaski County circuit judge stripped of the authority to preside over capital-murder cases.

The ruling expands a 2017 order by the Supreme Court that prohibits Griffen from presiding over any litigation involving the death penalty. Previously, he'd heard challenges to the legality of the state's lethal-injection procedures, disputes over whether prison officials had illegally withheld information about the chemicals used in executions, and questions about whether authorities had legally obtained some of those chemicals.

Griffen is a critic of the death penalty but says his personal opinions have never influenced his legal duties and that there is no evidence to show that they have. In a news release, Rutledge said the high court recognizes that Griffen cannot preside fairly over death penalty issues.

"I applaud the decision today by the Arkansas Supreme Court granting our petition to confirm that Judge Wendell Griffen remains permanently disqualified from overseeing any death-penalty cases, including capital-murder cases," Rutledge said. "As the Arkansas Supreme Court has repeatedly confirmed, Judge Griffen's inappropriate conduct demonstrates that he cannot be a fair and impartial judge when it comes to the death penalty."

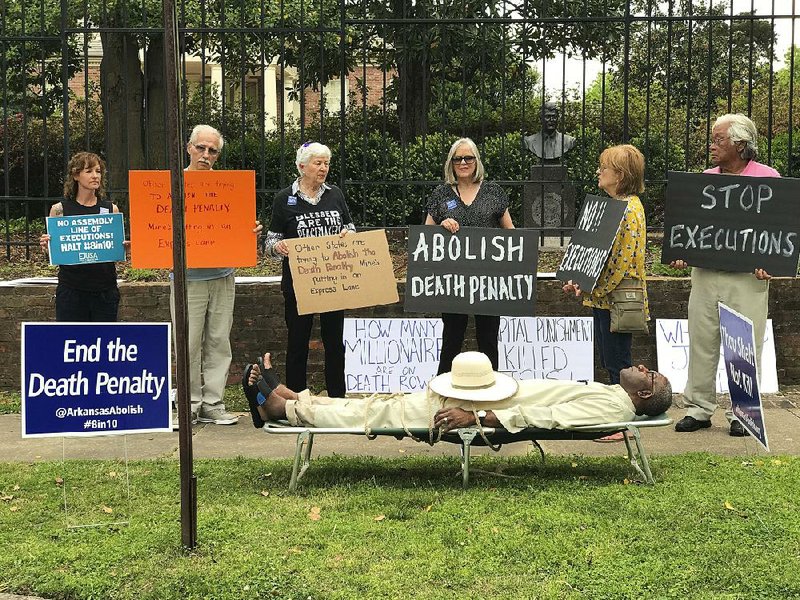

In 2017, Griffen's capacity to fairly preside over death-penalty cases of all types was called into question by some when he appeared at a Good Friday prayer vigil at the Governor's Mansion with members of his church congregation. A minister, Griffen lay on a cot in a white suit with ropes loosely binding him in what he later said was an effort to emulate Jesus Christ, who also had been executed.

The vigil was to call attention to the death penalty because the state was about to resume executions after a 12-year hiatus. Sign-holding protesters stood around Griffen while he was photographed on the cot, but he said none of them were members of his church and that those with him had not actively protested.

Around the same time of his appearance at the mansion, Griffen temporarily blocked prison authorities from using one of the three execution drugs. The judge was acting at the request of a pharmaceutical supplier that had just sued that same day to stop the state from using the vecuronium bromide, claiming that prison officials had tricked it into providing the paralytic.

Griffen's order would have lasted only about four days, until a hearing could be held, but Rutledge appealed to the Supreme Court, which canceled his order, then issued its prohibition to block Griffen from execution-related cases of any kind.

The justices never explained their reasoning for acting against Griffen, who complained that he never got a chance to defend himself before they acted. The dispute between Griffen and the justices resulted in ethics investigations that ultimately went nowhere while Griffen's efforts to sue them in federal court were thrown out

In 2019, the high court rebuffed Griffen's request for reconsideration in a ruling that stated he had waited too long to ask the justices to change their minds. Griffen also had asked all of the justices to recuse.

A scheduling change late last year brought on by the retirement of Judge Chris Piazza resulted in one of Piazza's capital-murder cases being transferred to Griffen's court. The docketing shift ultimately landed two of the 20 capital-murder cases filed over the past year in Griffen's court. Piazza's departure reduced the number of courts handling criminal cases from four to three.

The move raised questions about the scope of what the justices had intended in their 2017 order.

Could Griffen hear capital-murder cases where prosecutors are not seeking or cannot seek the death penalty? In circumstances where prosecutors had not decided whether to pursue execution, could Griffen preside over the case until they decide to seek the death penalty then have another judge take over?

With those questions unanswered, prosecutors asked Griffen to recuse while emphasizing that they did not doubt his integrity or abilities. Griffen declined to give the case to another judge in a ruling that stated he was ethically obligated to retain jurisdiction over all the cases in his court as long as he can preside over them fairly and impartially.