Before Halloween was all about candy, it was about pranks.

Our custom of moaning that kids are no longer able to go door-to-door innocently treat-or-treating predates this pandemic, as I am sure Dear Reader remembers. Parents started bemoaning that "loss of innocence" somewhere in the late '70s and early 1980s when cable TV alerted us that the neighbors we saw everyday were fiends (see arkansasonline.com/1026real) just waiting for a chance to slip pins and razor blades into fresh apples.

I'm sure you remember because I remember, and I also remember thinking, "Innocence? Really?"

But trick-or-treating as a harmless, cute way to get candy from strangers wasn't even firmly established in the 1950s, when I was little. Tricks were common, and they could get rough. The night before Halloween, Mischief Night, was the worst. I remember a terrifying gang of boys my sisters called "gatecrashers" crowding against our front door, demanding candy. I was 4 years old.

"Go away," my sisters said. "All we have is soup." So, probably they knew these boys.

In the 1960s, mean kids might waylay little trick-or-treaters, or pour paint on pets, or throw eggs. If you owned a cat, especially a black cat, you brought it indoors before Halloween.

And also, yes, there was the glorious adventure of slipping unnoticed by mean boys through a landscape transformed by dark, with alien glowing porches and jack-o'-lanterns. Unsupervised, we skittered across our town, even onto the streets paved in dirt. I remember one grocery sack that filled up with an impossible amount of candy. So much candy the sack tore.

But more than half the adventure was our conviction that danger was everywhere.

Of course there were adult-sanctioned, safe celebrations, too, the church or school carnivals, dance parties or "play" parties, ghost stories, cheap party favors and shoddy costumes -- and none of it was especially modern. All of that was dirt-common in Arkansas 100 years ago and earlier, as is plain from the archives of the Arkansas Democrat and Arkansas Gazette.

Also common? A conviction that a hard-hearted and very unsentimental police department kept the night from being "as weird and unholy as it was in the 'good old days'" (Democrat, Oct. 30, 1920).

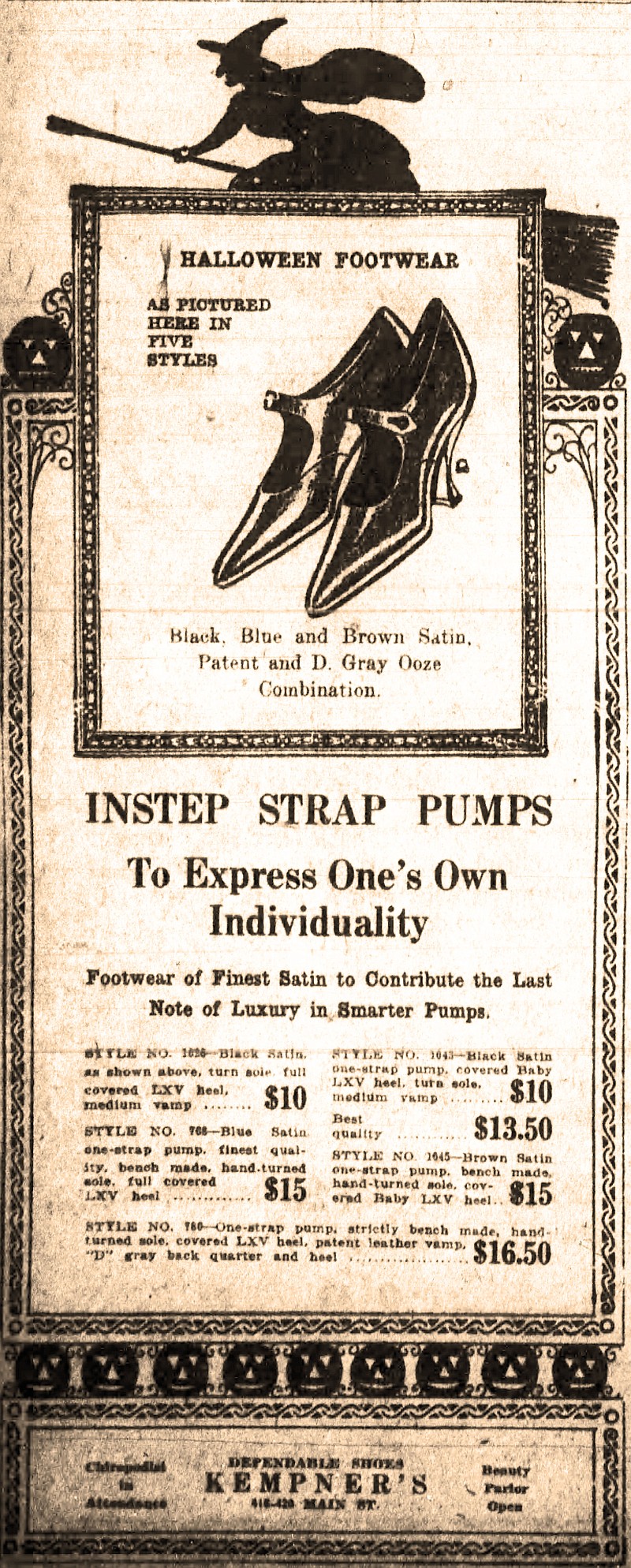

In the weeks before Halloween 1920, both papers carried ads for special food, clothing and party favors. For instance, an ad for The Gus Blass Co. in Little Rock offered:

• Pumpkin lampshades and candle holders decorated with witches, black cats and goblins, 10 cents and 15 cents.

• Halloween caps, very novel, 10 cents.

• Halloween horns, black and yellow noise makers, 10 cents.

• Halloween place cards, also bonbon cups, pumpkins and wicked little goblins, 5 cents to 15 cents.

"Make your selections now -- avoid disappointment," the ad warned. "You will find it possible to make your Halloween party much more successful by the use of these clever favors. They add a touch that can be secured in no other way."

The society pages were full of reports of private and public parties, luncheons, auction bridge parties, church bazaars (Episcopal, Methodist, Presbyterian, Catholic), masquerades, dances, Halloween-theme bridal showers. School parties were benefits, and they included familiar activities: booths, fish ponds, parcel post for miscellaneous packages and fortune telling.

The Southern Trust Co. turned its monthly meeting into a bash in the bank lobby, including three girl ghosts in "weird attire" who led guests one by one to a fortune teller's booth, where many learned their fate from the presiding witch.

Party reports continued beyond the first week of November. Everyone from the Embroidery Club to the Convalescent House at Camp Pike had a party of some kind for Halloween. I lost count of how often the Gazette society writer described a color scheme as "the Halloween idea" and the food served as "dainty."

Halloween fell on a Sunday that year and, then as now, was celebrated Saturday night instead. As the Democrat explained, Oct. 30 was "Halloween practically, if not chronologically" because all good children were supposed to be in bed or at church on Sunday night. The paper actually said, "So, if your windows are peppered with corn, your doorbell goes crazy or your gates jump off their hinges, you may know that the spirits of Halloween have visited you" Saturday night.

The real Halloween idea was not a color scheme but that dead people's spirits walked the earth on that one night, and they were up to no good. Impersonating those spirits inspired pranks. The boys who became today's long-dead great-great-great grandparents made great headaches of themselves across this state.

Evidence from the Gazette of Sunday, Oct. 31, 1920:

Halloween Gives the Small Boys a Chance

Delight in Annual Pranks, Carting off Gates and Ringing Doorbells of Citizens

Dwellers in the residence districts last night were well aware that it was Halloween. An epidemic of ghost-walking swept the city and the streets were alternately filled with groups of small boys imperfectly disguised as ghostly visitants, and with irate householders demanding immediate restoration of gates and sections of fence which had vanished in thin air.

The costume effects were simple and effective, consisting for the most part of sheets and pillowcases surreptitiously borrowed from the home supply. The advantage of the disguise lay in the fact that approximately 100 percent of the impromptu witches wore similar attire.

Cohorts of vandals bore off building materials from houses under construction, while lone marauders concentrated on flank attacks on doorbells. And in the meantime an older generation dwelt long and lovingly upon the advantages of some of the less admirable methods of the Salem forefathers.

On Nov. 3, the Gazette reported that someone had stolen the cushions out of the automobile of A.L. Rotenberry on that Saturday night.

Mr. Rotenberry has had hopes that the stealing of the cushions were a Halloween prank and that they might be returned if the children taking them knew to whom they belonged.

They belonged to the brother of Burl C. Rotenberry, chief of police. A.L. was a lawyer active in state politics; that summer he'd served as a special collector of overdue taxes.

Another Halloween tradition 100 years ago appears to have been fireworks. In the awful tradition of fireworks, this happened:

Dorothy Lea Rankin, aged eight, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. E.H. Rankin of Walnut Ridge, died Sunday afternoon from burns sustained at a Halloween party Saturday night. With several other children, Dorothy was playing with some fireworks when her clothing became ignited.

Halloween in the good old days. Scary.

Email: