CONCORD -- Kenneth Moore had a big idea for his rural school district -- train everyone to be a mental health counselor.

The Concord School District, like one in every five Arkansas school districts, does not have an in-house therapist, full or part time, nor a formal contract with a mental health care provider, according to an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette analysis of public records provided by more than 250 school districts.

Like many places, the district doesn't have the budget or nearby providers to lean on for student mental health care. Some do, periodically, visit campus to see their clients.

Still, Moore, the superintendent there, wanted to help his kids.

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

His plan? Train the faculty and staff to spot warning signs and take action.

"Basically, we're going to become some extra counselors and people that kids feel comfortable to go through," Moore said.

It could have come at a better time, but Moore is happy that it's happening at all.

Anecdotally, the pandemic has made student mental health care worse across the state, putting a wedge between struggling students and help, but Arkansas educators saw holes in the school mental health safety net long before the coronavirus pandemic.

The societal safety net for kindergarten-through-12th-grade schools has for years been expanding to include mental health services. In Arkansas, tens of thousands of students take advantage of it each year, to the tune of tens of millions of dollars in health care billings.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wyTUEDWZnvw]

The pandemic hasn't just delayed efforts to improve care and school safety. In some cases, it has entirely blocked students from treatment.

Without wider internet connectivity and the built-in accountability of the school setting, many mental health care providers have struggled to reach as many students as they were before.

The conversion rate of students referred by schools into patients has plunged at Families Inc., one the state's largest providers of school mental health services. The conversion rate was about 80% before the pandemic, according to CEO Mark Thurman. It's about 50% now.

At the same time, hundreds of student clients have been discharged from care, either because they asked to be discharged or because they simply stopped showing up. But a low percentage of those clients actually met the treatment goal, said Shelly Horton, the agency's school-based coordinator.

Laquietta Stewart and her fellow school counselors at The Academies and Jonesboro High School School tried to measure the impact of the pandemic on their students' mental health, surveying pupils in August.

[Interactive map not loading above? Click here to see » arkansasonline.com/1115services/]

Students were scared, bored, worried, sad and angry at school or the government. Some said they were fine.

The survey results became a part of faculty professional development sessions before the start of the school year.

The presentation gave pause. The survey responses could have been written by the educators themselves.

"It was a powerful moment, seeing the student responses and realizing they were just as confused and emotional as we were as adults," said Stewart, who is also president of the Arkansas School Counselor Association.

So counselors advised teachers on incorporating more "social emotional learning" into their teaching. That meant letting students talk about their well-being and taking cues from the students about how best to conduct class, Stewart said. Then, educators were reminded to take care of themselves and manage their own anxieties.

Surveys like this are one way many schools are keeping an eye on students' mental health, said Sharon Hoover, co-director of the National Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

[COVID CLASSROOM: Read more stories from this series » arkansasonline.com/covidclassroom]

Non-verbal cues are often major indicators of a student's well-being. When a student is learning virtually, or when half of the student's face is covered by a mask, monitoring is harder.

Yet teachers and guidance counselors are important players in getting students help, eventually leading to referrals to mental health care providers -- often, a provider that serves children at the school.

Sometimes, the help stops with the counselor, if the student's problems aren't severe.

One Cabot High School student, who asked not to be identified, told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that she'd felt overloaded with schoolwork as a remote student and that she was doing the work just to get it done, but she wasn't really learning.

She had to quarantine this fall and missed out on some senior events.

"Everything was just sad," she said. "It really hurt my mental health a lot. I just didn't want to wake up in the mornings. I just wanted to stay asleep."

She hadn't seen a mental health professional before the pandemic, so she went to the counselor after a particularly stressful day.

The counselor told her to take a break, put down her schoolwork, take a nap and do something for herself. So she did, and it helped.

She's continued to see her counselor, whom she said is sufficient for her needs. But she knows other students need more intensive therapy than what school counselors typically provide.

SCHOOL EMPLOYMENT

The pivot to remote learning, and its continued use, has made schools' role in mental health care more obvious, Hoover said.

People also are more aware of mental health issues, she said. However, Hoover anticipates a greater investment in mental health in schools, including for educators.

Schools have partnered with outside mental health providers to address students' needs, as their own staffs capable of providing mental health care lags behind recommended levels.

During the past academic year, Arkansas school districts employed more than 1,500 psychologists, social workers and counselors -- mostly counselors -- data from the Arkansas Department of Education show.

National professional organizations for school psychology professionals, school social workers and school counselors suggest ratios of those professionals to students far lower than Arkansas or most states can meet. Arkansas school districts would collectively need to employ more than 4,000 additional people to meet those groups' recommendations.

The Education Department acknowledges a "clinician shortage" in helping address children's mental health needs. But spokeswoman Kim Mundell noted that the now-available Arkansas Department of Human Services hot line can help people in crisis.

Services at schools are more convenient for children and their parents. Having them available on campus can increase children's access to care.

During the pandemic, insurers have adjusted their coverage policies to account for new ways of providing mental health care. That includes video calls and phone calls, which continue for many clients today.

Although the ways in which students can get services has increased, many students stopped attending counseling sessions who might have continued if not for the pandemic, mental health care providers theorize. Some disappeared temporarily. Others still haven't returned to therapy.

MORE THAN DOUBLED

Educators say that, compared with previous decades, children in recent years go to school with more troubles and needs that aren't being met at home.

Some are bullied on social media. Others are raised by extended family members amid growing drug abuse among parents.

Schools can be a safety net for children -- a temporary haven from problems much larger than education -- if the schools are properly staffed and funded, officials say.

Statistics indicate Arkansas children have a greater need for mental health care services than most states.

Arkansas ranks among the worst states -- 47th in the nation -- with 27.1 % of children who have suffered from at least two adverse childhood experiences that can result in mental and other health issues throughout life, according to the United Health Foundation's annual health rankings. Adverse childhood experiences can include economic hardship or witnessing domestic violence.

Suicide has increased among Arkansas children in most years since 1999, according to available federal data. From 1999 through 2018, 394 Arkansans 18 or younger died by suicide.

About 10% of those youth suicides, 39, were in 2017.

Nationwide, 2,388 people 18 or younger died by suicide out of about 77.7 million people in that age group in 2018. That's a 68.8% increase in the number of suicide deaths since 1999, while that population has increased by only 2.3%.

Since 2011, the number of Medicaid-eligible children who received mental health care at school in Arkansas has jumped from about 15,000 to nearly 37,000 last school year. State Medicaid data reviewed by the newspaper show taxpayers spent $32.7 million in 2011, the earliest year for which data are available, on the school services.

By 2018, the numbers more than doubled, with Medicaid paying $75.7 million to serve about 37,500 youths at Arkansas schools.

MISSING THE STUDENTS

Without a full-time therapist at her daughter's school, Pamela Green doubts her child would have gotten the help she needed. Green, a single mother of two, works all day and couldn't take her daughter to therapy in the middle of the workday, or at the end of the day, either.

"The probability would have been that she would not have seen someone, and I would have been trying to do it with my zero knowledge," Green said.

But Green's daughter clearly needed to talk to someone more qualified than Green.

Her daughter had become withdrawn. She didn't laugh anymore. She no longer wanted to take pictures or leave her bedroom.

"She just was not the child I knew," Green said. "I knew something was definitely really wrong."

So, last fall, Green sent her to a therapist. Green was lucky to have that option.

In the Smackover-Norphlet district, an outside provider goes to the school to serve students only once every two weeks.

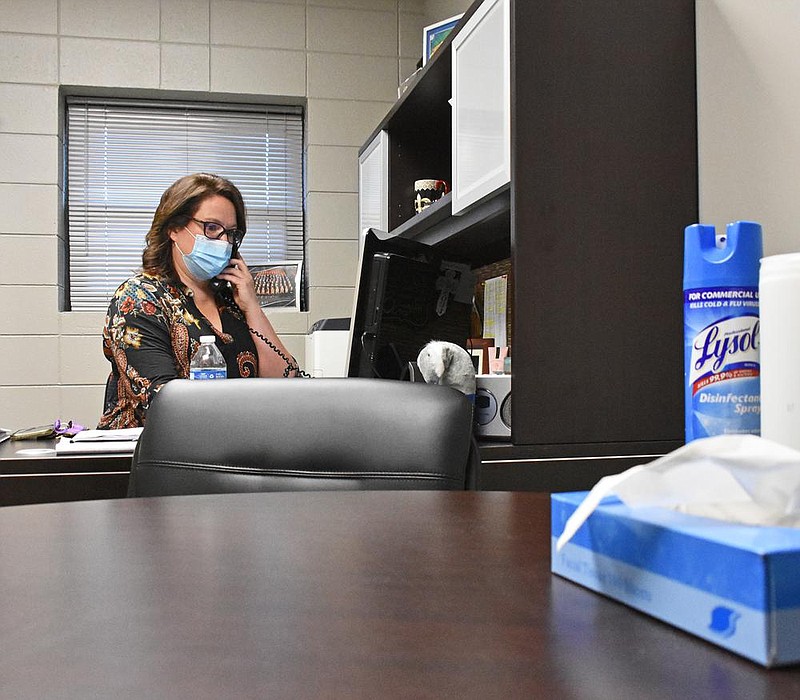

Becky Dixon is a rare school-employed therapist, available all day, everyday to see kids who need help.

After months of weekly visits, Green's daughter was opening up. She was suffering from troubles far worse than teenage hormones. Finally knowing what was going on, Dixon and Green were able to help her.

She started spending time again with her brother and with Green, playing games and watching movies, smiling and letting people take her picture again.

"It's almost like watching someone come back to life," Green said.

But when the pandemic arrived in Arkansas, Dixon and Green, like many others, had to figure out how to make it still work.

This spring, many of Dixon's youngest clients dropped off of her radar, despite her best efforts. She thought about those without stable home lives, who saw her because of those home lives.

"I have some that I provided weekly therapy to that I haven't been able to get a parent to call me back," Dixon said this spring.

Some students she has been able to connect with hid their faces during sessions, which made connecting with them more difficult.

Dixon tried to work with her clients in whatever way kept them getting the help they needed.

That included FaceTime, which she can't bill Medicaid for. She drove to El Dorado to meet with a family at a park. She can't bill for that, either.

"But it was necessary," Dixon said. "It was needed."

Most of her students have returned to see her on campus, where she meets with them several feet away in her office, both wearing masks. She has to regularly sanitize the surfaces and the wide array of sensory objects that she's used for years to help kids open up.

When they play with something in their hands, she said, their filter goes down, and they talk more. That's one of the differences in-person services can make.

But Dixon can make only so many adjustments.

Before the pandemic, Dixon hugged and high-fived kids in hallways. She wanted to remind them they were loved.

"I miss the students," Dixon said this spring. "I miss being more a part of their lives, that connection, because it just doesn't work the same over phone or telemedicine."

She's back on campus now, as are most of her clients, although occasional quarantines send students and educators back home.

Dixon has to keep her distance on campus. Walking through the hallway, everyone passes without touching anyone.

Dixon will have to go back to remote therapy for the next two weeks. The school district will be closed this week because of coronavirus.

LEARNING TO CHECK IN

Keeping students, and their teachers mentally healthy and keeping students engaged in school are now similar efforts.

In some places, schools are slowing down, setting aside more time for wellness check-ins and discussions about how everyone is doing.

That reduces the burden of schoolwork that children, and even teachers, are struggling with and helps educators stay on top of how everyone is doing and who needs help.

In Concord, the district has set aside Fridays as days for curriculum review, enrichment and wellness check-ins. Teachers can pay extra attention to virtual students those days, while in-person students often work in labs. Moore, the superintendent, also decided to hire content-specific tutors, which also helps lessen the load on teachers, who he says have "basically been asked to run two schools at the same time."

Those changes occurred after the district polled employees and students to see how they were doing and what obstacles they were facing.

"That's when we realized we had an issue," Moore said. "The change in environment is overwhelming. Students had instructional gaps from the spring."

Discipline issues haven't been worse, Moore said. The social distance and the fear of getting sick have been jarring.

This district knows about mental health struggles better than most. Last year, a 14-year-old student died by suicide in a campus bathroom.

The district has no formal agreements with therapists either in-house or outside. Sometimes, therapists from out of town visit the high school to see existing clients, and they'll meet with anyone else necessary. But that's it.

That's why Moore decided to train his faculty and staff.

Last week, two district educators were trained, virtually, at Texas Christian University's Karyn Purvis Institute of Child Development. They learned to spot signs of trauma in kids and how to address it.

Later, they'll lead several days of professional development for the rest of the district's educators. Originally, even parents would be included, but the pandemic dashed those plans.

Moore won't say a lack of mental health care contributed to last year's on-campus suicide. He wasn't working at the district at the time, and said educators were aware that the student was struggling and got the youth counseling outside of school.

When Moore arrived on campus last year as the new superintendent, he noticed the gaps in mental health needs and available care.

"Our staff wasn't properly trained on how to notice those behaviors or have any tools in their toolbox to address them immediately," he said.

Educators and employees across the 409-student district are ready for more training.

School nurse Delite Fife this fall has seen more young children at school with stomachaches caused by nerves. She's seen it before, but this semester it's different. Kids are afraid; they're scared of contracting the virus and spreading it to a loved one. One student's father died of covid-19 in October.

Fife sees students as they sit in chairs several feet from her desk or in the makeshift patient room -- a corner of the office with see-through drapes. Between the spaces is a black board with neon words of affirmation.

"I am loved/I am valuable/I am needed/I am accepted/I belong here and I have a purpose/I am safe here/And no matter how bad things seem, somehow some way/It can and will be Okay!"

Fife has been getting training in recent years to spot mental health needs in kids, once she realized emotional issues can sometimes manifest themselves in physical form. Now, she sees herself as a key player in getting kids help. She helps get the students into counseling and makes sure they go.

"I think we can get to a lot of our students before crisis mode," Fife said.

Priscilla Johnson, the elementary school counselor, is one of the two educators who attended the training. Minutes after helping an elementary school classroom learn better "whole body listening skills" -- using dancing to Miley Cyrus' "Party in the USA" as an end-of-lesson instructional tool -- she said educator-student connections are a major difference maker in students doing well overall.

"At the end of the day, that's what it's all about, connecting with one teacher," she said.

About ‘Covid Classroom’

“Covid Classroom” is an ongoing series examining the effects of the corona-virus pandemic on kindergarten-through-12th-grade public education across Arkansas. The project is reported and presented by the news staffs of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette and the Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, with the support of the Walton Family Foundation.

The series is produced independently, with no input in the research, writing or editing from the funding organization.

All elements of the project will be available online for nonsubscribers.

“Covid Classroom” is one of several similar projects around the country involving 16 news organizations and 50 newsrooms.