Nitin Agarwal is a high-tech detective, a social media Sherlock Holmes, searching the internet for computer-generated misinformation that can undermine national security, free elections or public health.

Defense-related agencies have repeatedly tapped Agarwal, a University of Arkansas at Little Rock information science professor and cyber sleuth, to study the topic, and his findings have been disseminated to military brass and to NATO allies.

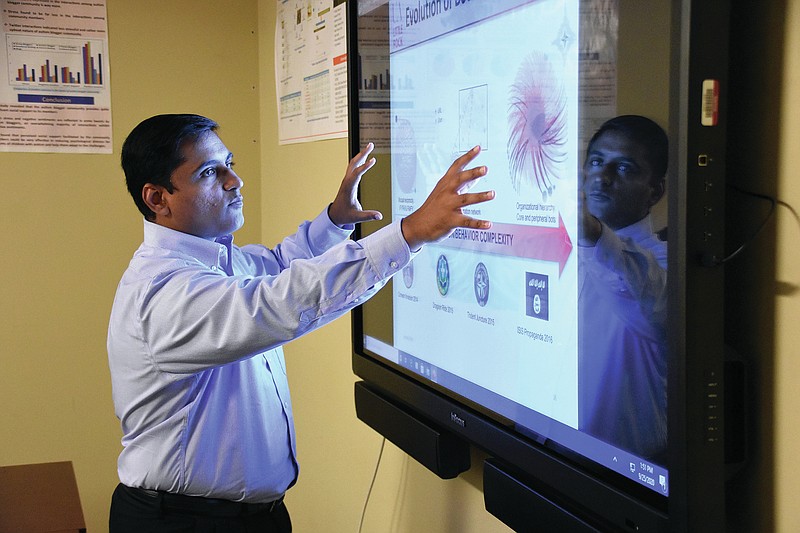

The school's Collaboratorium for Social Media and Online Behavioral Studies -- or COSMOS for short -- Laboratory, which Agarwal founded in 2014, has received more than $15 million in funding over the past six years, including grants from the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Office of Naval Research, U.S. Air Force Research Lab, U.S. Army Research Office, U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, NATO, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Arkansas Research Alliance and the Jerry L. Maulden-Entergy Endowment.

Given the importance of the work, the COSMOS Lab, with backing from the Arkansas Department of Higher Education, has been designated as an established research center at the school.

Bots, also known as web robots, aren't inherently good or evil, Agarwal says. They're simply technological tools.

Apple's Siri is one example. Amazon's Alexa is another type.

So are webcrawlers, which scour the internet for information.

"When you talk about bots, they're nothing but computer programs that can help or assist humans in their day-to-day tasks or the tasks [that] do not require a lot of creativity," he said.

Bots can help you make a hotel reservation or schedule a hair appointment, he said.

But they have also been used to exaggerate someone's social media standing.

"In Japan, you can actually go to a vending machine and buy a thousand followers on Instagram. Just swipe your card and you're getting 1,000 more followers or 1,000 more likes on your photos," Agarwal said.

Some bots help save lives, he said. There are suicide prevention bots that can interact with people who are severely depressed.

Others are "used to disseminate misinformation ... or to amplify hate speech," he said.

Agarwal focuses much of his attention on these malicious bots, he said, studying the "tactics, techniques and procedures" that they employ.

Bots have been deployed during natural disasters to discourage minority-group members and immigrants from using government shelters, he said.

Undocumented workers, for example, have been told that they won't receive assistance unless they bring proper paperwork, such as green cards or proof of citizenship, to the site, he said.

"What these bots do is they try to create chaos," he said. "A malicious group just wants to create confusion within the society."

In other instances, bot developers seek to sow discord, he said.

"The idea is to use bots to amplify or rile up both sides of the argument, both sides of the debate, and create more and more divisions and polarize the crowds," he said.

Their aim, he said, is to "unravel the fabric of society, basically."

The United States has been targeted, but so have many other countries, he said.

Canada was targeted during last year's elections, he said.

"What we found was extremely disturbing," he said. "These bots were creating entire websites filled with false narratives, images [and] videos."

That wasn't something Agarwal could have envisioned as a Ph.D student at Arizona State University.

"I started my research in social media back in 2005-2006, [studying] how social media is going to give voices to everyone," he said.

During the Arab Spring, activists used social media to challenge nondemocratic regimes in northern Africa and the Middle East.

Repressive regimes eventually learned how to use social media for their own ends, he said.

Russia, China and Iran are major instigators of misinformation, he said.

During the U.S. presidential election campaign, foreign powers are again attempting to deepen the fault lines in American society, Agarwal said.

"Certainly, there are more such malicious activities in 2020 as compared to 2016," he said.

Non-governmental fringe groups are also using bots to exacerbate tensions, he said.

The focus is broader than electoral politics. They're also spreading misinformation about covid-19 and other topics, he said.

Once a false narrative is posted online, it can spread quickly, he said.

The damage, he said, can be real and long lasting.

"These bots are able to manipulate our beliefs and behaviors and also erode trust in our scientific and democratic institutions and values," he said.

Agarwal came to UALR in 2009 after earning his doctorate.

"I've been here since then and I've enjoyed every moment of my stay at UALR," he said.

He not only studies the bots and their messaging, but he also is able to trace, in many instances, where the bot originated.

Along with Samer Al-khateeb, an assistant professor at Creighton University, he is the author of "Deviance in Social Media and Social Cyber Forensics."

Joni Lee, UALR's vice chancellor for university affairs, said Agarwal has built a highly respected program in Little Rock and is now "known as a national player in this field."

"He recruits from all over the country, all over the world," she said. Students "come here specifically to work with him."

Brian Berry, UALR's vice provost for research and dean of the graduate school, said Agarwal is making a difference "on the national and international level, not just within the state."

Jason Mollica, a professor in the school of communication at American University in Washington, said social media manipulation is "a very, very hot topic."

If UALR is emphasizing this type of research, it's a good thing, he said.

"That is something that could be very, very helpful to not only just Arkansas but also the nation and hopefully, in many ways, the rest of the world," he said.

"Bots and misinformation will not go away," he said. "When it comes to digital and social media, we're going to continue to need to study [it ]."