With its doors closed, as they are at so many places where we come together to create and consume art, Art Ventures gallery staff have had a lot of time to reflect. For the July exhibition, the art space is looking back on work created in the gallery and the communion the artists shared as they worked in response to live models, once upon a time. “Face & Figure” features pieces from 12 artists created during weekly workshops when Art Ventures was still open. The virtual exhibition highlights not only the human form, but the visceral energy that can develop from a room full of artists working, in front of each other, from the same living subject.

“There is a huge challenge to seriously drawing from the live model. Usually you can feel the intensity of the artists working under a time constraint to produce something they can be satisfied with,” artist Tim McSweeney muses. “The concentration levels of the different artists, the presence of the model holding absolutely still, the subtle sounds of hands working to paper, the furious pace when the timekeeper announces ‘10 more minutes’ … The whole process is one I find absolutely thrilling.”

“It takes a little time and practice to get over yourself and paint in front of other people, especially in front of an experienced artist,” Joanna Reid continues the thought. “It’s good to quiet our egos and just be in the moment. It’s a three-hour time limit, so you have to pay attention and stay on task. You hope to get into a state of flow that is almost meditative while you just focus on what you’re doing.”

“I believe very much that the activity of working directly from the live model has value on many levels: It is an intellectual, emotional and communal pursuit,” adds Neil Callander, also included in the exhibition. “Our little community of artists developed a nourishing weekly ritual. I miss our ritual.”

“Face & Figure” can be accessed several ways, including a virtual reality option for those viewers with the appropriate apparatus. The experience takes one through a virtual gallery setting — viewing each artists’ works hung on walls throughout the space. Here, four artists further discuss the value and the challenge of working with a live model:

Q. How would you describe your figure work to a viewer?

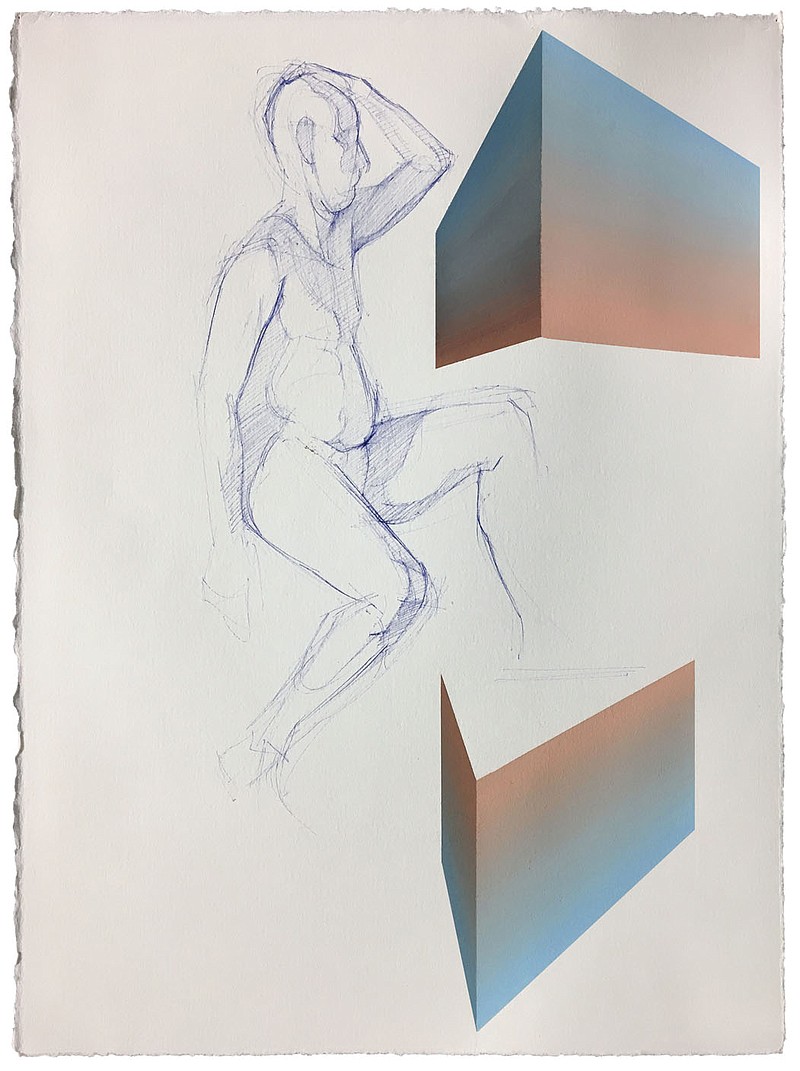

Callander: Drawing the figure from life has become a regular part of my creative practice — it’s an exercise that keeps my eye and hand coordinated. I draw with ballpoint pen, recording my structural and anatomical observations in line and completely stopping when the timer dings. The results are not always great — maybe one in every five drawings is kept — but the ones that resolve feel remarkably fresh. Then, in the studio, I pin up the successful drawings. Some are chosen to have a second act, and I add color gradations in gouache which have a similar fresh feeling.

Deb Manley: My approach to working from the figure is immediate and visceral: I want to capture the gesture and my first impression of the model’s presence without being hindered by technical details of achieving an exact likeness. I try to convey emotion or attitude even in my quick sketches. (The three in the Art Ventures NWA exhibit are 10- and 20-minute sketches.) My figure drawings feel empty to me if I can’t convey something in the eyes or the posture that is revealing in the model or maybe even more in how I, myself, am feeling. I’m not drawing a scene that is separate from myself but an interpretation of an experience in which I, too, am a participant.

Q. What drew you to the medium and/or materials you work in?

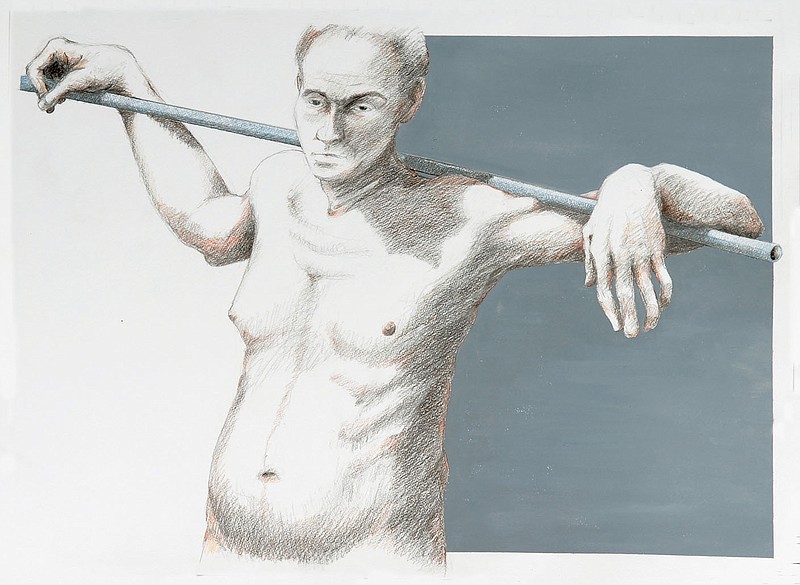

McSweeney: The medium I use for drawing I have used for some years. I start with a toned paper, in gray or beige tones. I find that this instantly provides me with the mid-tones, saving time and work! Then I only have to supply the outline, and after erasing possibly half as many lines as I put down on paper — which I consider almost a sculptural process of adding/removing material — until getting a believable likeness of the true form, then I can really dig into it with the shadows and lastly, the highlights. Mostly this would be with black and white color pencils, trying to stay away from graphite (which shines in light reflection). Color pencils of a fairly high quality are softer, which I prefer. Sometimes I will use a brown or gray color pencil to help breath life into the rendering, and on a few occasions, India Black ink.

I try to pack as much information into the live drawings as possible, so that I can continue to develop them after the session is over. Not included in these three examples [in the exhibition] are other drawings where I have added even more and different pencil colors, which brings the finished piece closer to a painterly appearance. These require additional hours of work to complete, of course.

Reid: I grew up drawing everything, almost always in black and white, and developed quite a bit of confidence with those mediums, so I started to shy away from color. It can be almost like starting over when you introduce color. I have a friend whose then-husband is a well-known artist, Tim Tyler, [and] helped me piece together the necessary supplies. He started me out with a very limited pallet, and I’ve mostly stuck with that. I almost always use a warmer and cooler version of each of the primary colors, plus white, and I combine those seven paints to make all of the colors I see. I’m bad about overworking my oil paintings until they get “mushy” or “muddy,” so I’ve recently been working in acrylics more because they force me to be more decisive. In the show, [one piece] is painted in oils, and the other two paintings are in acrylic. It’s still hard to not overwork my paintings, honestly.

Q. How do you hope having your work surrounded by/in conversation with other artists’ pieces will impact the viewer’s connection with the exhibition’s theme or with your own work?

Callander: I hope the viewer has an appreciation for the layers of humanity on display. A trusting relationship with the models must be built; the individual artists must be focused and open, almost like an athlete; there is a continuation of an art historical line of inquiry; our community of artists support and inspire one another.

Manley: This is a tough question for me. All artists invest something of themselves in their work, and we’re all very different in our individual disposition and approach to the figure. It’s both refreshing and revealing to see how individual artists approach the same subject matter — especially, I think, the human figure because, in a very real sense, it is so close to all of us, as artists or viewers. An exhibition such as this one allows these subtle differences to be presented in context, so that we can clearly observe that visual art is more than simply recording objective details, but involves revealing something of ourselves as artists, something which viewers also may find in themselves — as a resonance, perhaps, which they feel with the images or the artists’ particular approach and treatment of the figure.

Q. What can you tell me about the value you find in working with live models? How do you feel this practice challenges you as an artist? What do you hope to convey about each model in the works you create?

Manley: The complexity of the human form makes it a difficult subject, but it informs all of my art. It’s changed the way I see everything. Trees, for instance, are the closest subject to the human form for me. I find myself studying trees in much the same way I study the human form. One sees so much more when life-drawing than when drawing from a photo or video. Working from a model challenges me to connect my inner reality with the outer reality of my life in a way that is more than merely symbolic: it’s visceral, personal. Something, someone real and undeniable is “out there” for me to see and respond to. It demands my presence, my honesty and attention in a way that affirms and reinforces my own identity in relation to an outer reality that is inhabited by another living being, not just a photo online without weight and volume — sheer physical presence.

Something is communicated by physical presence, in working with the model, that transcends my ability to describe. It’s always personal and individual, intrinsic to the artist/model interaction. It’s left to the line and form to express visually what we, hopefully, understand in a deep, intuitive way.

McSweeney: I think what I strive to convey is something of a story about the person. I have often rendered the model looking straight at the observer, for instance, and that gaze can speak volumes. Or by adding just a small prop — like a pole or eyeglasses or a teacup — a story is implied. Even the pose itself can imply a great deal for the imagination of the viewer. These are aspects that I love to bring to “just” a simple figure drawing. Again, not the norm among most artists, for many of whom the figure is a learning session rather than a finished work, which is great. But then to think back at the immense narratives that Michelangelo delivered … that can be something I would love to be able to do more of. Someday, perhaps.

Reid: The thing I’m always hoping to convey to a viewer is gratitude for our visual experiences. I always TRY to simplify my colors and shapes to point out how all of these pieces really do exist and come together to create our experience, and learning to look for those colors and shapes is an exciting way to look at the world around us. If my model is old and wrinkled or awkward or unusual in any way, then that’s all the better for pointing out how beautiful ALL of it is.

Looking Back:

The Other Side

Lewis Williams is a figure drawing and portrait model with Art Ventures. Here, he is portrayed by artist Adam Benet Shaw as part of the “Face & Figure” exhibition. Williams illuminates his experience from the other side of the easel:

Q. How did you get into modeling?

A. I always try to challenge myself mentally. I don’t always succeed, but I do try. Last year I wanted to do something that was bold, daring, and something that a lot of people would not do. How the notion of becoming an art model got into my head, I have no idea, but it did. I called around with no experience and with no one to recommend me so finding a position was a little difficult. Art Ventures got back with me a day later, and I’ve been posing ever since.

Q. Do you decide your own poses, or do you receive any direction?

A. I get the majority of my inspiration from online sources: Pinterest, YouTube, Google, etc. Getting my poses from some dance moves has also been useful. For example, if I’m watching a video of someone dancing, I would take a portion of a move and use it as a pose. I try to be resourceful.

The majority of my poses I decide on my own, but I’m open to any new poses or directions on how to pose to facilitate the class better. The artists are paying for the classes so I want them to enjoy every bit of it.

Q. Do you feel any sense of responsibility to create an especially dynamic or actionable pose to challenge the artists?

A. My role as a model with Art Ventures is to inspire artists and to stimulate their visual senses, to give them something new and inspiring to draw. Yes, I do feel that responsibility, and I try to incorporate it when I can. Believe it or not, it really does take some strength training and practice, because holding a seemingly “easy” pose for five minutes can cause a person to sweat.

Q. Some of the figures in the exhibition are clothed and other are nude. Do you have a style you primarily model in? Are their any misconceptions or stereotypes about the practice of nude modeling you would like to dispel?

A. I’ve done both clothed and nude, but if I had the choice I would choose nude. Don’t get me wrong, clothed/portrait modeling is fun. You can dress up and wear something that you think is cool or that sends a message. But modeling nude/figure modeling gives me that mental challenge that I desire. Literally, I’m nude in front of total strangers. I’m pretty sure that ranks high on the Challenge Meter. And it’s fun. I do understand how that may sound to some but for me it’s an outlet. Kind of like a mental colonic. No stress — I’m relaxed.

One misconception, and probably the biggest one, is that many people think that nude modeling is one big perverted art show. That is not true. Now, don’t get me wrong, it can be. That’s why it so important for any aspiring models to be safe, and to speak with their gallery manager or agent if they are not feeling safe. Thankfully, all of my experience has been wonderful.

Being nude is something that is natural, but this world has turned it into something shameful and has over-sexualized the human body. When you do that, people thinks it’s wrong — but it’s not. It’s not the practice that needs to change, it’s just people’s mind frame about it. Will one more nude drawing change that? Who knows.

Q. Do you like to see the images the artists produce? And are you ever surprised by the way you are represented?

A. I’m so curious to know what artists produce. The way they see me can be so interesting.

I really enjoy seeing my clothed/portrait drawings. The portraiture sessions are usually three hours long, and I’m staying in that one pose. Three hours is quite a bit of time for an artist to really get your likeness, and from the few that I had the chance to see, I was not disappointed at all.

FAQ

‘Face & Figure’

WHEN — Virtually on display through July 31

WHERE — artventures-nwa.org

COST — Free to view; donate to Art Ventures at the website

INFO —871-2722, artventures-nwa.org