When six mysterious villains in blackface broke Morgan Williams and two other prisoners out of the Pulaski County jail at Little Rock on March 31, 1835, Arkansas Gazette editor William Woodruff blamed land pirates.

An outlaw gang was active in the Arkansas Territory, stealing horses, counterfeiting and, most notoriously, harvesting cash from slaveholders by kidnapping enslaved people or enticing them to flee and then selling them back to their owners, only to steal them again and sell them back again, and then again, and again.

These organized bandits had murdered an investigator, according to Woodruff. They had a base amid barely penetrable swamps between the White and Mississippi rivers and were said to be associated with a legend then in the making — purported criminal mastermind John A. Murrell. Read the Central Arkansas Library System Encyclopedia of Arkansas essay about his overblown notoriety here.

Reporting the jailbreak that April 7, Woodruff fingered one escapee, Fielding G. Secrest, as a member of this gang.

Williams merely was accused of murdering Isam Pelton while drunk (see story on Page 1D). The third prisoner was Hiram, a black man enslaved by Emzy Wilson. Hiram was the second slave to flee Wilson that winter and was in the jail "for safekeeping."

"From information we have received, there can be no doubt that the band is numerous, and that they have spies and accomplices scattered through every neighborhood in this section of the Territory, and probably every part of it," Woodruff wrote. He (once again) advocated tracking the gangsters and lynching them.

He added there was "no doubt" gang accomplices had freed the prisoners. Many in town believed the gang had a frontman there, and a prime suspect had been arrested and questioned the day after the escape.

"Although it resulted in his discharge — the proof not being sufficiently positive to justify his committal — still no mitigating circumstances appeared during the course of the examination to weaken the strong impression on the public mind which caused his arrest, and which still exists as to his guilt," the Gazette said.

Historian Margaret Ross mentions this episode in Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years, 1819-1866. The suspect was lawyer and newspaper entrepreneur John Steele, who also left town that April, "none too soon for his own safety," Ross writes. Steele had defended accused slave-stealers in court, successfully, and he was expert at finding missing slaves, for a fee.

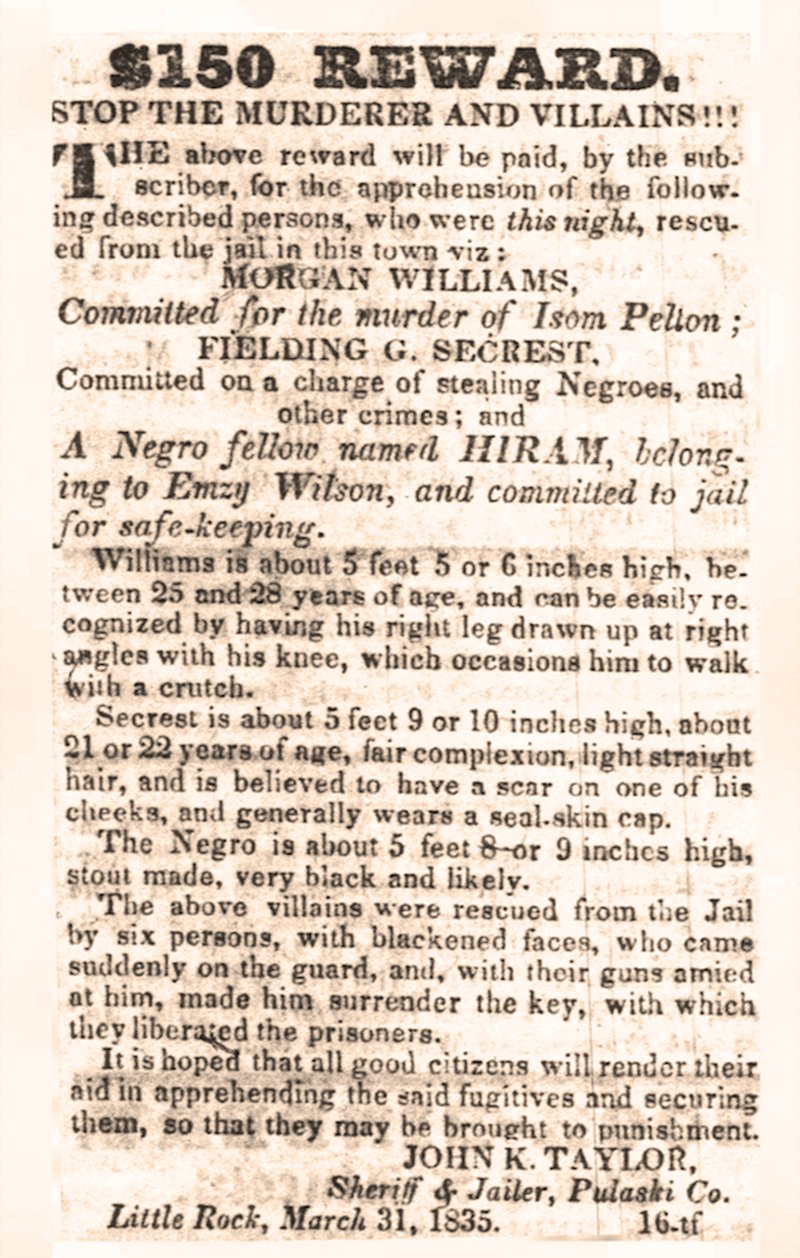

An advertisement from the county sheriff posting a reward of $150 for all three prisoners was published in the Gazette and the Arkansas Times and Advocate.

The Gazette noted that witnesses had seen Secrest and Hiram fleeing together, headed for the White River. But Wilson took out an ad April 10 in the Times and Advocate offering $50 for Hiram's return and stating he was not likely to be with the other prisoners. The ad appeared several times through early June that year.

If Secrest or Hiram ever were caught, it is not evident in the newspapers' digital archives.

[RELATED: Little Rock’s first public hanging]

Style on 01/13/2020