In the spring of 1931, an African-American domestic worker named Rosa McCauley was trying to elude a drunken white man who was pursuing her around the house where she was employed in Montgomery, Ala.

She was 18, stood 5-foot-2 and weighed 120 pounds. She called the man "Mr. Charlie." He had poured himself a whiskey, put his hand around her waist and offered her money.

Web Watch

Read more about Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words at loc.gov/exhibitions….

"I felt filthy and stripped naked of every shred of decency," she wrote later. "I was no longer a ... self-respecting teenage girl, but a flesh pot, strumpet to be bargained for and parceled as a commodity from negro to white man."

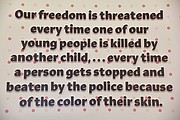

She told him she hated him, and all white people, for what they had done to blacks.

The teenager who escaped the clutches of "Mr. Charlie" -- a negative term for a white man -- would later be known by her married name, Rosa Parks.

And her handwritten account of an early encounter with racial and sexual oppression is part of a new exhibit about the civil rights icon that opened in December at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

"He need not think that because he was a lowdown dirty dog of a white man and I was a poor, defenseless helpless colored girl that he could run over me," she wrote. If he wanted to rape her, he'd have to kill her first.

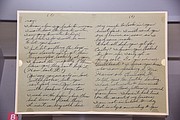

The undated document -- one of its 11 pages is on display -- reveals another aspect of the Rosa Louise Parks who is renowned as the diminutive woman who in 1955 refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus to a white man.

What followed was the historic 380-day black boycott of Montgomery buses, a U.S. Supreme Court decision desegregating the city's public transportation and the modern civil rights movement.

But the new exhibit, Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words, shows, among other things, the inner woman, marked by the plight of African-Americans from an early age, determined to fight, yet buffeted by events and isolated by her fame.

"I want to feel the nearness of something secure," she wrote as her public image grew. "It is such a lonely, lost feeling that I am cut off from life. I am nothing. I belong nowhere and to no one."

"The line between reason and madness grows thinner," she wrote.

The exhibit portrays a woman bearing an enormous public burden in the face of racial terrorism and three centuries of repression, while trying to keep her ties to her husband, Raymond, her family and her faith.

The display of rare documents and photographs comes from a 10,000-item collection covering her family from 1866 to 2006, according to the library staff.

The material is part of the collection of Parks' belongings that was purchased by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation and deposited with the library in 2014 on what was initially a 10-year loan. The loan was turned into a permanent gift in 2016.

Parks, whose grandmother was enslaved, was born in Tuskegee, Ala., in 1913. She died in Detroit in 2005 at the age of 92, famous for a solitary act of defiance 50 years earlier that etched her name in the annals of American history.

The exhibit includes the big family Bible that recorded births and deaths on her mother's side of the family. The Bible is being displayed for the first time after its conservation at the library, says Adrienne Cannon, the exhibit's curator.

It includes a document in which Parks recalls a childhood encounter with a white boy about her own size.

"He threatened to hit me," and balled up his fist "as if to give me a sock," she wrote. "I picked up a brick and dared him to hit me. He thought better of the idea."

But when she mentioned the incident later to her grandmother, the elder woman responded with a warning, according to a companion book about the exhibit by the library's writer and editor, Susan Reyburn.

"Gal, you had better learn that white folks is white folks and how to talk and not talk to them," Parks recalled her grandmother saying. "You better stop being so high strung or you will be lynched before you get grown."

You can't "talk biggity to white folks," she recalled her grandmother saying.

Parks wrote of herself: "I cried bitterly [saying] that I would be lynched rather than be run over by them. They could get the rope ready any time they wanted."

Parks' frightening description of her encounter with the man who tried to assault her, whom she did not further identify, reveals another little-known aspect of her life, says Reyburn.

"It was something she never spoke about," Reyburn says. "Never talked to her family about it."

Parks was well aware of the historical role of rape in the era of slavery and segregation.

"I thought of my poor great-grandmother who in slavery days could not do more or know more than to be used and abused by the slave owner," she wrote in recounting the incident.

"She was bred, born and reared to serve no other purpose than that which resulted in the bastard issue to be trampled, mistreated and abused by both negro slave and white master," she wrote.

Reyburn says that Parks knew that many black women were still being sexually attacked by white men, and she often would seek out victims to document their stories. She was frequently the only person they would talk to.

"She is aware from her own personal experience how common this is, and how terrifying this is," Reyburn says. "So she ends up counseling a lot of women. And all of this was before the bus" boycott.

In Room LM-102 of the library's James Madison Memorial Building, Cannon, the exhibit curator, says she spent days poring over Parks' neatly written manuscripts -- the "loops and scrolls"of her elegant penmanship.

"I was getting a picture of a different person" than the one frozen by history on the bus, she says. "I was surprised by ... the poetics of her writing and of the rawness of much of what she wrote, of her willingness ... to reveal her innermost feelings and thoughts."

It was a glimpse into Parks' soul, Cannon says.

"Is it worthwhile to reveal the intimacies of the past life?" Parks once wrote. "Would the people be sympathetic or disillusioned when the facts of my life are told? Would they be interested or indifferent?"

NAN Our Town on 01/09/2020