Some 3,000 years ago, the preacher in Ecclesiastes proclaimed, "Of making many books there is no end," but how those books are published and enjoyed has changed dramatically. Even in the past decade, we've witnessed an industry transformed by new economic forces, technological innovations and consumer attitudes. Here are 11 trends over the past 10 years that changed how we read:

1. Chains crumbled as indie bookstores rebuilt. Borders went bankrupt in 2011 and closed more than 600 stores. Barnes & Noble teetered precariously but was saved last year by Elliott Management Corporation, which operates Waterstones in Britain. The bright spot during this past decade of retail destruction was the resurrection of independent bookstores. From a low point in 2009, their ranks rose by more than 50%. New and newly toughened store owners figured out how to create connections with their communities and offer a personal experience that Amazon, their online nemesis, can't. B&N hopes to survive by imitating the indie model and giving more reign to store managers. In a final irony, Amazon now maintains 21 actual bookstores around the country -- with more on the way. (Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

2. Everybody started listening to audiobooks. As platforms and listening devices became more convenient, the audiobook market enjoyed double-digit increases almost every year over the past decade. Last year, half of all Americans age 12 and older said they had listened to an audiobook. Publishers responded with slick new productions that rivaled the golden age of radio drama. At the extreme end, the audiobook of George Saunders' Lincoln in the Bardo employed a record-breaking cast of 166 people, including Ben Stiller, Julianne Moore and Susan Sarandon.

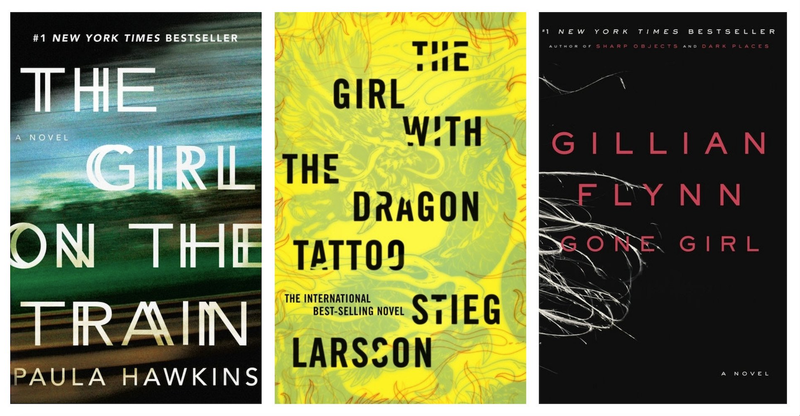

3. Girls took over. In 2005, the Swedish publisher of Stieg Larsson's first novel called it Man som hatar kvinnor (Men who hate women). When it appeared in English, the title was sexed up to The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. That change set the ink for a trend that would spill across the next decade. In 2012, Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl sold more than 2 million copies. Paula Hawkins kept that momentum moving with The Girl on the Train, which sold more than 15 million copies by 2016. But the "Girl" phenomenon wasn't just a case of copycats gone wild. It also heralded a talented new class of women barging into the old boys club of thrillers and changing the rules of the game.

4. Graphic novels became the superheroes of publishing. Long after Art Spiegelman's Maus won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, graphic novels still struggled for mainstream respect. But in the 2010s, that uninformed condescension morphed into wild enthusiasm. As sales accelerated, publishers, teachers, librarians and especially Hollywood took notice. Old stories like Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird became the subject of graphic adaptations, and traditional fiction and nonfiction writers such as Roxane Gay, Anthony Bourdain and Ta-Nehisi Coates were drawn to the genre. In 2016, March, the third volume of U.S. Rep. John Lewis' experience during the Civil Rights movement, became the first graphic novel to receive a National Book Award. And just weeks before the decade ended, The Washington Post published its first graphic novel: The Mueller Report Illustrated.

5. Kids books -- real and faux -- became the latest weapon in America's heated political battle. Goodnight Trump, based on Margaret Wise Brown's classic, was one of many such parodies that poked fun at the president. But a different segment of these politicized children's books had a serious intent. Innosanto Nagara published a board book called A Is for Activist to get toddlers off their high chairs and into union halls. Books about Hillary Clinton, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and other liberal heroes were aggressively marketed. On the other side of the aisle, Rush Limbaugh published a series of time-traveling novels that take "Rush Revere" back into patriotic moments of American history.

6. E.L. James brought erotica out of the backroom. From her humble beginnings posting "Twilight" fan fiction under the pen name Snowqueens Icedragon, James developed an invaluable literary empire. Her Fifty Shades trilogy, originally published by a small Australian press, was already a phenomenon by the time Vintage picked it up in 2012 and amplified its reach around the world. That year, Random House made so much money from Fifty Shades that every single employee got a $5,000 bonus. James sold more than 152 million copies; her novels were the best-selling books of the decade. But more significantly, her success helped create a viable market for countless other novelists writing erotic fiction.

7. Instant-printing finally got real. For years, the promise of instant book publishing hovered just over the horizon. This past decade, it came true. In 2011, Politics & Prose joined a growing collection of bookstores that could print paperback books on demand from a catalog of several million titles. Print-on-demand combined with self-publishing e-book platforms was even more significant for authors who couldn't get -- or didn't want -- a traditional publisher. While most titles sold very few copies, some genre writers -- such as Andy Weir and Amanda Hocking -- found immense success. The new technology also allowed traditional publishers to respond much more quickly to unexpected demand.

8. Children's publishers finally got serious about diversity. In 2014, the University of Wisconsin at Madison's School of Education found that less than 3% of newly published children's books were about black people. Using the hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBooks, they launched a social media campaign that led to the creation of a nonprofit organization dedicated to increasing the representation of minorities in young people's books. Publishers and librarians expressed new resolve to feature books and authors that look more like America as a whole. Data released in November by the University of Wisconsin indicate a fourfold increase in the number of children's books about black people and similar increases in the number of books by and about Hispanics.

9. Political books became political badges. The extraordinary partisanship of this past decade fueled a tremendous market for polemical books. During the Obama administration, conservative writers Edward Klein, Dinesh D'Souza, David Limbaugh and others served up one denunciation after another. By the time Donald Trump came into office, that marketplace was running hot on the left and the right. Trump's perceived glories or evils drove sales of exposes, hagiographies and memoirs, almost all designed to confirm rather than inform or challenge one's fealty. The effect, in many cases, was to transform these ephemeral tomes into pennants in paper, badges to proclaim one's allegiance. That trend reached its zenith in the closing weeks of the decade when the Republican National Committee bought up thousands of copies of Triggered by Don Trump Jr., to give away to donors.

10. TV producers gorged on new novels. Under the old model, authors hoped to sell rights to their novels to movie producers, but the proliferation of streaming TV platforms during this past decade created vast new opportunities for fiction writers. Game of Thrones, The Handmaid's Tale and Outlander became must-see TV. Memoirs such as Piper Kerman's Orange Is the New Black and Lindy West's Shrill found new life on the small screen. Science fiction and fantasy fans were rewarded with a galaxy of new series, including James S.A. Corey's The Expanse, Neil Gaiman's American Gods and Lev Grossman's The Magicians. This trend accelerated as the decade drew to a close, with announcements that Susan Choi's National Book Award-winning Trust Exercise and Richard Flanagan's Booker-winning Narrow Road to the Deep North will be made into series. What's most encouraging is the way these TV shows send people back to the original books, creating a virtuous circle of watching and reading.

11. Libraries and publishers clashed. This past decade, millions of readers discovered the convenience of downloading e-books from public libraries. But not everybody was happy about this development: Publishers worried that they were losing sales. Last year, one of the Big Five publishers, Macmillan, imposed an embargo on purchases, restricting libraries to just a single copy of each e-book during the first two months of publication -- when demand for a title is typically strongest. That action sparked widespread condemnation from librarians and a boycott against Macmillan e-books by dozens of library systems. Both sides claim the other is threatening their survival. Although a significant percentage of these library downloads take place on Kindles, Amazon's proprietary publishing imprints refuse to sell e-books to public libraries. Penguin Random House distanced itself from Macmillan and proclaimed its support for libraries as agents of increased literacy and discoverability. But this battle is still heating up as we head into the next decade.

Style on 01/05/2020