Shoes were on the move in autumn 1919.

In August, burglars broke the bars on the alley window of the Saifer Bros. shoe store at 604 Main St. in Little Rock and took $45.90 in cash and $300 worth of shoes. As the Arkansas Democrat reported, owner Harry Saifer felt hurt but not discouraged. He knew he had heavy fall shipments of shoes coming.

And then:

• Sept. 8, according to the Arkansas Gazette, a showcase in front of Pfeifer Bros. store at Sixth and Main streets was broken and several pairs of shoes were stolen.

• Sept. 10, at 3 a.m., a patrol officer called Saifer at home: The barred window in his alley had again been broken and the store burgled. This time he felt discouraged as well as hurt.

Shoe thefts continued into October, as we know from a handful of small items about young men facing theft or burglary charges.

Prices for food and most manufactured things had skyrocketed, and shoes became the poster child for the "high cost of living," usually abbreviated in headlines using periods: H.C.L. And there were a lot of shoe headlines.

As we have seen (Old News, Sept. 9, 2019), famous industrial magnates in Chicago who had been accused of profiteering were mocked for bragging that they were fighting the H.C.L. with wise shoe conservation habits. Rather than buying new, they had their old shoes repaired. They lectured "the workingman" not to be such a spendthrift.

And then one of them was found to just have ordered more than $125 worth of brand new shoes.

• Sept. 7, the Gazette reported L.R. Ashby's approval of a plan by the Little Rock Merchants' Association to refund train fares for out-of-town shoppers. Owner of the Walk-Over Boot Shop, Ashby added that there were always unusually high-priced shoes on the market, but the prices of medium-priced shoes remained "practically the same."

And, he said, the Walk-Over Boot Shop only stocked medium-price shoes.

Also Sept. 7, below "The Many Uses of Alcohol," an article in the Gazette urged that shoes fatigued beyond repair should be soaked in water to remove dirt, have their nails and thread plucked out and then be reduced to a thick pulp. Leather pulp was great for wallpapers and screens, book parts and mats for framing photos.

Carriage builders press it into sheets which are invaluable for the roofs of the most luxurious vehicles.

Also explained by the Sept. 7 edition's fascinating filler stories was the word "shoddy." Today, we talk about "shoddy shoes," and shoes are shoddy; but also there is shoddy, and it is:

The soft rag wool obtained by tearing up long-fibered, unfelted goods, but in a wider sense it signifies all manufactured wools as contrasted with natural wools and includes mungo (obtained from short-fibered rags), extract (obtained from mixed cotton and wool in which the cotton is reduced to cellulose by the action of sulphuric acid and the wool fiber preserved), and, finally, the flocks and wastes of different kinds which are collected in the woollen and worsted factories from the carding rooms, weaving sheds and fulling mills.

Fulling mills. Mungo!

"Shoddy" as an adjective was already applied to shoes in 1907, specifically to shoes with paper insoles and bridges that quickly wore apart. Before the Great War, a campaign for ethics among retailers urged them not to take advantage of urgent, impoverished customers by selling them shoddy shoes but to instead educate them to the longterm savings in paying another $1.

By 1919 — who'd a thunk it? — the ignorant poor required education to the contrary, to stop them from spending all their money on expensive shoes. A national campaign by a shoe industry anxious to shake the label "profiteers" showed up in the pages of the Democrat and Gazette as full-page ads. They laid the blame for higher prices on spendthrifty working people and ... cows.

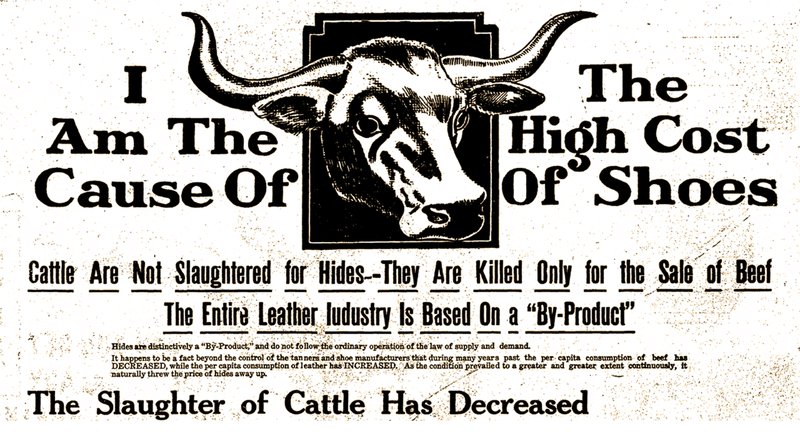

Shoes, the ads explained, were innocent in their own high prices. Shoes were merely a byproduct of cattle slaughter, and cattle were not getting themselves slaughtered in adequate numbers to keep shoe prices down. One ad I enjoy a lot said:

It happens to be a fact beyond the control of the tanners and shoe manufacturers that during many years past the per capita consumption of beef has DECREASED, while the per capita consumption of leather has INCREASED. As the condition prevailed to a greater and greater extent continuously, it naturally threw the price of hides away up.

I like that "away up." Public beef-eating had indeed declined during the war because the government ordered everyone to eat it less, so soldiers could have more. And the leather generated by military cow consumption was used in war-essential manufacturing. But the war was over, replaced by race riots, labor strikes and alleged profiteering.

This ad also had a chart densely packed with large sums in four columns that purported to document "official figures" for declining cattle slaughter over the past 30 years. This chart is sweet gibberish.

On Sept. 20, Gov. Charles Brough convened a special session of the Legislature — the third session in 1919 — to correct some road bills passed in the earlier sessions that led to inadvertent outcomes. While they were at it, Brough said, they should pass a law against profiteering.

The Democrat reported that "numerous senators are said to be violently opposed to the passage of the anti-profiteering law, especially solons from the smaller towns and rural communities."

Only three senators spoke for two bills. All three senators were heckled and their proposals dismissed as "the fruit of peanut, candy and popcorn politics" — but not before they inspired magnificent oratory.

Sen. George F. Brown (of Dallas, Cleveland and Lincoln counties) likened the cry of business to be "let alone" to the cry that went up when Christ ordered the devils into the hogs and they ran down into the sea.

"Christ disturbed the hog business that day and a great howl went up. We're called here to Little Rock to disturb another kind of 'hog business' and the same sort of a cry goes up."

Sen. Lee Cazort countered that the "real trouble" was in the expensive habits of the people, and that if folks quit wanting to wear $12 silk shirts and $18 shoes they might have an easier time making ends meet.

He also charged that not everyone was working who should work, and that an increase in production by labor would result in a decrease in prices through the operation of the laws of supply and demand.

If these sound like arguments people have today, could be they are. Only there isn't much of an American shoe industry left to kick around. Dang those cows.

Email:

Style on 09/16/2019