Robert L. Goodman had been missing for three weeks before the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat reported it in April 1919.

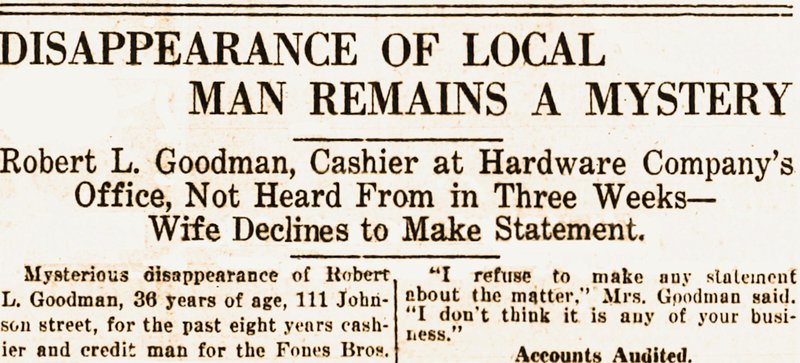

The Democrat had the news first, on April 28:

Mysterious disappearance of Robert L. Goodman, 36 years of age, 111 Johnson street, for the past eight years cashier and credit man for the Fones Bros. Hardware Company, 116 North Main street, who left his work over three weeks ago with permission for a few days of rest, which he said he needed, Monday remained unexplained, and was said to be causing officials of the company as well as the family of Mr. Goodman considerable anxiety.

Roxie, his wife, had declined to comment, the paper added:

"I refuse to make any statement about the matter," Mrs. Goodman said. "I don't think it is any of your business."

Auditors were going over the books at Fones, the report continued. Also, one Mrs. Alma Horn, who had been Goodman's stenographer, had left work a day or two before Robert vanished, and she also appeared to have vanished.

Mrs. Horn had divorced her husband in 1918, citing ill treatment.

People could disappear in the early 20th century without a hue or cry arising, but Robert's absence became front-page news, which suggests he was a figure of interest. But I mention that only for the sake of Occasional Reader. Faithful Reader already knows he was, because today's column is Part 2 of a story Old News began to poke April 29.

We met Robert Lee Goodman and his wife, Roxie, Daughter of the American Revolution and giver of "elegant" dance parties, parents of two little girls. And we learned that Robert's adventures had amused a Democrat columnist in 1917. The Rocks From the River of Life column reported his humorous take on his military service and his escape with the family cat out a second-story window while their home was engulfed in flames.

We also learned about his presidency of an unusual hat shop.

The Quality Shop opened at 606 Main St. on Aug. 22, 1912. The Gazette noted that its two "important innovations" would be providing a restroom for ladies and explicitly excluding black people.

The Democrat reported a "formal opening" almost a month later, Sept. 16. Invitations had been sent to "the ladies of the city." Those invitations stated the officers of the shop: Robert L. Goodman, president; Leonard S. Goodman, secretary; E.T. Reaves, vice president; Frank Goodman, treasurer.

The Democrat report made no mention of the shop's motto, "The Store for White People Only," but nearly every ad during the shop's brief, heavily advertised existence in September-December 1912 did. Also touted were fancy prices for one-of-a-kind, imported and domestic hats and salesladies who spoke French and German.

Some ads suggest a certain desperation. One promotion offered $25 off to whomever bought the most expensive hat (it was a $60 hat). Another, in the Oct. 12 Gazette, stated: "It may cost us several thousand in business from this season to exclude the negroes from our shop but we know there are enough 'people who care' in Little Rock to more than offset this. Of course you couldn't care before. No merchant had the nerve to help you care. We had the will and the nerve. Are you 'one who cares?'"

I am delighted to report that The Quality Shop was insolvent by January 1913.

It held a closeout sale, and in February, Milady's Shop in the Kempner Building sold off the remaining stock of trimmed, $30-$60 hats, priced from 50 cents to $2.50.

A Gazette item in 1914 that seems to suggest Robert sued the store ("Robert L. Goodman vs. The Quality Shop") might have been the Gazette's shorthand way of noticing his appointment as responsible for settling its debts.

ROCKS FROM THE RIVER

I haven't told you about the rest of the 1917 Rocks From the River of Life column. It seems the Goodmans had cooped up a turkey outside their home and were fattening it for Christmas. Robert said he planned to stuff it "until it became a butter ball."

But it stopped eating. With Roxie watching, Robert entered the coop:

No sooner had he done so than it flew at him in rage and for the next five minutes there was the most animated argument in the coop that had been witnessed in the Eighth Ward.

He emerged with slashed trousers and scratches on his hands and face and a desire to execute the turkey.

I suspect the columnist was wrong about the duration of that argument — what unarmed person could last five minutes against an enraged turkey? Also, our friend Helpful Reader thinks the columnist was wrong about another fact: the war in which Robert had served. Helpful Reader did some math and noticed that Robert would have to have been 12 or 13 during the Spanish-American War. More likely, he served in the Philippine-American War of 1899-1902.

Thank you, Helpful Reader.

BACK TO PART 2

Robert was in the news several more times before 1919: He had jury duty in 1916; he joined a volunteer group of firemen's helpers; and in April 1917 he drilled businessmen who wanted to be ready if drafted for the Great War. In July 1917, he enlisted in the Army.

Roxie paid her poll taxes to vote in 1917. She also made the social pages a few times that year and the next. In October 1918, the Democrat noted an elaborate Halloween party she gave for her daughter, "Little Miss Virginia Goodman" on her 11th birthday.

But once Robert vanished, in the course of three days — April 28-30, 1919 — he went from "cashier and credit man" to "embezzler," and Roxie became "embezzler's wife."

On April 30, the Gazette reported a warrant had been issued charging him with embezzling $1,200 in small amounts over a long period of time. The auditors said that "the false entries had been made skillfully, and a great amount of checking and rechecking was necessary to discover them."

Meanwhile, the reputation of Alma Horn got a save when Fones announced it had a letter from her postmarked in Bald Knob explaining that she had married a soldier and would not be back. Horn had been Goodman’s stenographer; she was said to have disappeared a few days before he did.

In May, Roxie filed suit in chancery court against Robert and an insurance company. Her attorneys posted a warning in the newspapers giving Robert 30 days to appear. She sought the cash surrender value of a 20-year policy for which he had named her as beneficiary. Her filing charged that he had deserted her, leaving nothing for the support of her and her daughters, Virginia and Margaret. In August, the court decreed she should get $1,000.

In April 1920, the Amoma class of Second Baptist Church held a party at 111 Johnson St., described as the home of Mrs. Robert L. Goodman.

In June 1920, she advertised the house for sale for $7,800. In March 1921, she posted it again, for $7,000. Also that month, she filed for divorce on the grounds of desertion.

The 1940 U.S. Census found a widow of the right age, one who was born in Tennessee and was named Roxana Goodman, living in New Orleans with her daughter, Margaret Goodman Michel. The Social Security Index lists a "Roxie Goodman" of New Orleans as dying in 1976.

What became of Robert? I haven’t a clue.

Style on 05/06/2019