Ray Charles could sing anything.

He often dismissed the imaginary boundaries that marketers and labels erected with the dictum "music is music." He had the ability to take all kinds of material and make something original from it.

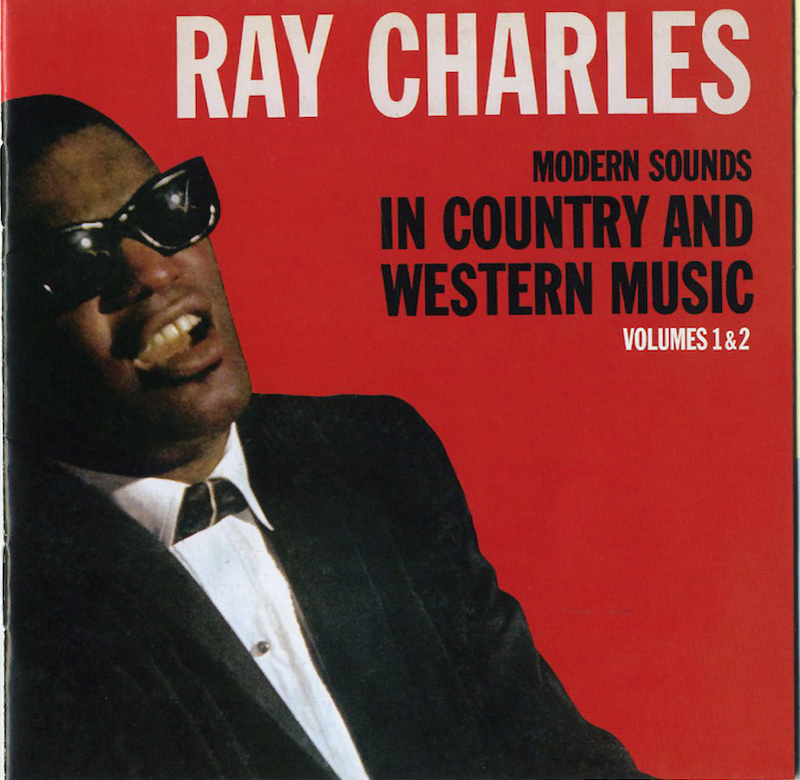

If you need to be reminded of that, maybe you should check out Concord Music's Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Vols. 1 & 2 , which they just reissued on CD and -- for the first time -- released to digital streaming services like Spotify, Tidal and Apple Music.

Charles, who died in 2004, was such a singular talent that it's difficult to imagine he started out as a copycat, performing note for note, nuance for nuance, covers of Nat "King" Cole and Charles Brown records.

It didn't take him long to get past that; after having a little regional success recording and arranging other people's records, Charles signed with Atlantic Records in 1952. It turned out to be an ideal match between artist and label, as both were just beginning to come into their own.

After demonstrating his ability as an arranger, bandleader and composer -- Charles arranged Guitar Slim's "Things That I Used to Do," the biggest R&B hit of 1954 -- Atlantic granted him an unprecedented amount of artist control. This paid off most obviously in November '54, when Charles suddenly broke through, finding his unique place in pop history. In a session produced by Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun and featuring David "Fathead" Newman on baritone sax, Charles crossed the gospel standard "Jesus Is All the World to Me" with gritty secular blues and made a noise both joyful and shattering.

That session also produced his first major hit, "I Got a Woman" -- the start of an impressive string of records that included "Hallelujah, I Love Her So," "Drown in My Own Tears" and frenzied call-and-response classic "What'd I Say" that made Charles world-famous. All were sung in his distinctive gruff, soulful voice and punctuated by his percussive piano and a bleating horn section.

In 1959, Charles abandoned the formula for soft balladry and came up with "Georgia on My Mind," perhaps his best-known record (which garnered his first Grammy Award). In 1961, John S. Wilson, The New York Times jazz critic, wrote that "almost every aspect of nonclassical" music was being "blanketed [by] the varied talents of Ray Charles a pianist of exceptional range who can move skillfully from basic, root blues to a modern linear style."

Wilson noted that Charles' small band had developed into one of the finest jazz groups playing and that the singer's voice, "worn through years of whooping and hollering in his blues performances, shows a rough, leathery quality in his relaxed approach."

Charles was the rare pop artist who couldn't be contained by artificial genres or segregated by race -- he was R&B, he was blues, he was jazz and he was rock 'n' roll. He was even a civil rights pioneer. In the fall of 1961, he made history in Memphis by becoming the first artist to play to an integrated audience at the municipally owned and operated city auditorium.

In the early '60s, Charles moved from Atlantic to ABC/Paramount Records, apparently without breaking stride. The hits kept on coming --"Hit the Road, Jack," "Unchain My Heart," "At the Club" -- and he maintained his reputation as a serious musician with the acclaimed straight jazz albums The Genius After Hours and Genius Plus Soul Equals Jazz. And then he decided to revolutionize country music.

Billy Joel said it best.

When Rolling Stone asked the piano man to write about Charles and his pair of 1962 releases, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Vols. 1 and 2, Joel emphasized the social impact of the albums: "Here is a black man giving you the whitest possible music in the blackest possible way, while all hell is breaking loose with the civil rights movement."

He's right. The importance of Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music can hardly be underestimated. At the time, country music was widely seen as the province of hicks. You could say it was a ghetto-ized genre, appealing primarily to a white, rural audience.

Producers like Chet Atkins, Owen Bradley, Steve Sholes and Bob Ferguson had success with integrating pop elements with their "Nashville Sound" which replaced the traditional fiddles, steel guitar and nasal twangy lead vocals of the honky-tonk sound codified by Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell with string sections, background vocals and crooning lead vocals and using "slick" production that employed a small group of highly adaptable and talented studio musicians known as the Nashville A-Team. Country songs were adopting pop music structures -- refrains and bridges were becoming much more common.

But if you listen to the country music that was played on the radio in 1962, you might perceive a certain creative exhaustion. While artists like Patsy Cline, Marty Robbins and Jim Reeves were successfully exploiting the "Countrypolitan" formula with sophisticated material, there were a lot of novelty-flavored records such as Jimmy Dean's opportunistic "P.T. 109" (and his corny epistle to his Communist Russian counterpart "Dear Ivan"), Rex Allen's bizarre "Don't Go Near the Indians" and Burl Ives' reedy folk ballads ("An Itty Bitty Tear," "Mr. In-Between"). While Buck Owens and George Jones staked claims for the Bakersfield and the hillbilly restoration, respectively, the country charts in 1962 were nearly as bland as the pop charts. (It was pretty dark just before the dawn of the Beatles.)

So it was surprising to ABC-Paramount producer Sid Feller when Ray Charles, fresh off the success of his 1961 jazz album Genius + Soul = Jazz, asked him to compile a set of country and western songs for the artist to record. But Charles was a self-determining artist -- he best knew his own strengths. Feller set out to get him some songs.

"I made calls to all the big country publishers, mostly in Nashville, but some of them were in New York," Feller told Michael Jarrett for the 2014 book Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. "They sent me about 200 or more of their best material on tape as well as sheet music with lyrics. I weeded through and found 40 of them that seemed great for Ray Charles. I edited all those little tapes they sent me and put it all on one reel. I sent it and copies of the [sheet] music to him. From that 40, he picked 12 and that became Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. But he picked them himself."

Most are recognized standards now: "Bye Bye Love," "You Don't Know Me," "Born to Lose," "Careless Love," "You Win Again," "Hey, Good Lookin'," "Take These Chains From My Heart," "Your Cheatin' Heart," "I Can't Stop Loving You," songs by the likes of Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, Hank Williams, Fred Rose, Eddy Arnold, Floyd Tillman and Don Gibson. Charles recorded four songs co-written by Jimmie Davis, who in addition to his music career was a two-time governor of Louisiana.

"After that, everybody in the country started making country and western records," Feller says. "Ray started that trend for pop people [like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra] to make country songs. A lot of the people said, 'Thank you for making us all rich ' A lot of publishers called me, 'Thanks for giving Ray my song.'"

Looking back on the full spectrum of Charles' career, it's not difficult to understand why he was drawn to the songs he eventually recorded -- he had played with hillbilly bands in Florida in his youth. And he really did believe that music was music.

Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Vol. 1, was released in April 1962 and topped the Billboard charts for 14 weeks. Vol. 2 was rush-released in September to capitalize on the success of the first album; many critics at the time thought it was superior.

The real genius of both records -- time has appropriately blurred the distinction between them; they were the result of the same sessions with the same players and sensibilities -- is that they aren't country records. They are Ray Charles records in that he chose to view them as he might any other pop song he was considering recording. He was not interested in preserving the rural character of the material, the swinging arrangements are pure light R&B and jazz -- Charles' particular brand of soul.

It's true that to modern ears the heavily layered strings and sweetened backing vocals might sound schmaltzy -- some have cited the record as a model of what went wrong with country music in the '60s; the heavy layers of strings and the sweetened backing vocals are difficult to take -- Charles' expressive voice manages to overcome the syrupy arrangements, which were, to be fair, by Marty Paich, Gill Fuller and Gerald Wilson, though none of them had the power to make Charles do anything he didn't want to do.

"He knew what he wanted and 99 percent of the time, it was the only answer," Feller says in Producing Country. "Once in a while, I'd come up with a suggestion. But I never did it over the PA system. Nobody else knew what we were discussing."

In a 1966 profile in Life magazine, Thomas Thompson wrote that Charles' "niche [was] difficult to define."

"The best blues singer around? Of course, but don't stop there. He is also an unparalleled singer of jazz, of gospel, of ballads, even unlikely enough, of country and western. He has drawn from each of these musical streams and made a river which he alone can navigate."

When you think of Charles you think of the husky, raw-scraped voice coming from deep within a barrel chest -- a voice that makes you think of busted things, of hot asphalt and cold clay. You think of the vast white smile and the heavy-looking opaque shades and the spastic rhythm of his side-to-side swaying. You think of '60s variety shows, of Dino and Sammy Davis Jr. and of whatever it means when they speak of soul.

The word genius crops up. That's what they call him. But you might think it is really too much to call Ray Charles a genius, too much like liner-copy hype, too much the word the record company wants you to use. There is another word that comes to mind: compromise. That's too harsh. It's only pop music after all, and if pop music can be said to be an artistic endeavor, then one must recognize that compromise is as much a part of the mix as aspiration.

In 1962, a black blues singer took country music to the world.

Ain't that America?

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 03/10/2019