A group of college freshmen crowd around a laptop screen in a local coffee shop to watch a video of a loud, pushy man standing at the corner of a busy intersection wearing glasses and holding a sign that reads "Make Love Not Birds" as he warns unassuming drivers not to trust the "Obama-drones." The owner of the laptop, Jordan Racundo, 19, proudly sports a "Birds Aren't Real" sticker on its back cover, entranced by the fanatic performer on her screen.

The founder and creator of Birds Aren't Real, Peter McIndoe, began his pseudo-activism-business back in 2017, achieving skyrocketing success as he plays within the margins of satirizing conspiracy theories and parodying viral trends, all to the head-shaking intrigue of his followers.

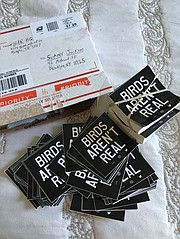

"When I told Jordan I'm friends with Peter in real life and he sends me free stickers, it was as if I had told her I'm in cahoots with a celebrity," says Summer Jackson, 21.

Birds Aren't Real

Birds Aren't Real began when McIndoe was a student at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. He jokingly debuted his first Birds Aren't Real protest at a women's march in Memphis, Tenn., and the stunt earned him mass attention on social media, accumulating almost 6,000 Instagram followers within three weeks.

Birds Aren't Real parodies a movement intended to bring awareness to the idea that live, wild birds have been replaced by government mandated drones that fly around and spy on unassuming Americans.

Through the brash assertiveness of his videos combined with the mechanics of a business and the lore of a conspiracy theory, McIndoe's entrepreneurial aptitude serves as an outrageous reminder to not take ourselves too seriously.

"Peter is the type of person that you're like always wondering if he's going to be famous for doing something amazing or for going to prison," Jackson says, laughing with a hint of apprehension.

Jackson is both a friend to McIndoe and a supportive fan of his performance art, saying that she fell in love with the absurdity of it all. She played an essential role in spreading Birds Aren't Real to Brooklyn, N.Y., during her time there last summer.

"I texted him, 'Hey Peter, I'm in Brooklyn all summer with some time on my hands and would love to help with 'getting Brooklyn woke,'" Jackson says. "He immediately responded back with 'I'm sending 200 stickers your way from Birds Aren't Real headquarters.'"

Jackson attributes Birds Aren't Real's rapid growth in popularity to a combination of McIndoe's ability to tap into something so obscurely random at the same time government conspiracies are so potent.

"We live in a time when memes and funny internet trends are amped way out of proportion. And people, especially young people, want to believe in and support Birds Aren't Real for the novelty of it."

Jackson's interest in Birds Aren't Real is founded in the sense of community and closeness within its following that coincides with McIndoe's art and his incessant commitment to staying in character.

"The whole thing is like an inside joke that no one has ever said before, and we're all simultaneously in on it."

It's a parody ... or is it?

UA student John Moritz, 21, claims he is more of a friend than a fan of McIndoe's work, as he frequently turns down opportunities to be featured in Birds Aren't Real promotional videos but enjoys watching McIndoe's success from a distance.

Moritz predicts that Birds Aren't Real's new-found attention has the potential to be a transitory sensation but is unsure if it can retain the endurance to achieve growing longevity.

"I'm not sure how many of Birds Aren't Real followers or fans are inspired by Peter's pseudo-activism," Moritz says. "He didn't necessarily reinvent the wheel, but his bizarre perspective and view of the world definitely brings a unique spin to it."

Moritz believes the movement is meant to satirize viral videos rather than American partisanship or government conspiracy.

"Peter is playing with the idea that society has really come full circle with people making fun of social media and the idea of 'going viral.'"

McIndoe was asked to participate in this story but was not available for comment. In an interview with Rachel Roberts, also a student at the UA, he explained his character "is a satire of this radical partisanship that we're experiencing every day. It's meant to put a light on the post-truth era."

"I'm well aware of the 'Birds Aren't Real' guy, and I am hugely amused by that whole thing," says Anna Merlan, author of the book, Republic of Lies: American Conspiracy Theorists and Their Surprising Rise to Power.

Although Birds Aren't Real is becoming increasingly popular and getting more play on social media, Merlan does not believe McIndoe's efforts depict a convincing parody for any kind of social movement, especially not something as intelligible and culturally rooted as feminism or social justice.

"The Internet loves an outlandish conspiracy theory and debating whether the progenitors of it are sincere or not," says Merlan.

When comparing the internet presence and assertiveness of McIndoe to other conspiracy theorists, Merlan admits he does share resemblances to some theorists who exhibit characteristics of "anomia," which is a belief in the instability of society and a deep pessimism about their own futures.

She said if he is going for satire, it's as though he is satirizing the conspiracy theorist themselves and their mistrust of the world around them.

"But it's not very good satire," Merlan says.

Social media stardom

As of 2018, friends and followers had helped McIndoe reach social media stardom by helping spread the "Feathered Gospel" and advertising their "Activism Gear" nationally and internationally.

In addition to a recent surge of internet traffic on all its social media platforms, Birds Aren't Real has accumulated an Instagram following of 46,000 and has gained the support of celebrities, such as YouTube star PewdiePie and the musical group Brockhampton.

Friends and followers have varying theories as to what helped catapult the sudden success of Birds Aren't Real, especially among middle-school and high-school aged students.

Jackson says the young fans were introduced to the idea by their Sky Ranch summer-camp counselors in the Dallas area, who are friends of McIndoe's and members of the "Bird Brigade." They would encourage their middle-school to high-school aged campers to chant "Birds Aren't Real" at camp events.

"Parents would get really angry because they thought their kids were getting taught something that wasn't true," Jackson says. "Older people are especially more sensitive, and some are firm believers that Post-Millennials will believe anything, or are becoming fully immersed in 'Fake News.'"

Moritz attributes today's political climate to playing a significant role in the success of Birds Aren't Real, being that distrust in the government is common nowadays.

"Some people are taking conspiracies, no matter how strange and illogical, pretty seriously."

People who know McIndoe and believe in him know that his creativity and business savvy surpasses the limitations of his first project, as his ability to create things off-the-cuff shows promise for many more successful visionary endeavors to come.

"With 'going viral' there's always a threat to longevity," Moritz says. "But even if Birds Aren't Real does somehow come to an end, Peter could put that energy towards something just as new and polarizing."

Elliott Omar is a senior from Memphis, Tenn., majoring in journalism and English at the University of Arkansas. She is a feature writer with a focus in human interest topics. Email her at [email protected].

NAN Our Town on 01/10/2019