FAYETTEVILLE -- Police and health professionals say they have a smoother process for working together now that the Washington County's crisis stabilization unit is open.

The 16-bed unit where people may stay up to 96 hours is just off College Avenue and Spring Street in Fayetteville. It is one of four units that comprise the state's pilot project to divert people with mental health problems from the criminal justice system.

Crisis intervention training

• Springdale has 26 of its 144 officers trained in crisis intervention.

• Fayetteville has 22 of its 129 officers trained in crisis intervention.

• Rogers has 24 of its 115 officers trained in crisis intervention. Four dispatchers have also been trained.

• Bentonville has four of its 82 officers trained in crisis intervention. All officers have completed a nine-hour training course focused on mental and behavioral health.

Source: Staff report

Fast facts

The state has set aside money to operate four crisis stabilization units in Sebastian, Pulaski, Craighead and Washington counties. The counties have to provide the money to construct or renovate the buildings. The units in Sebastian and Pulaski counties opened in 2018. The Craighead County unit opened in September.

The Washington County unit serves Washington, Benton, Madison and Carroll counties.

Source: Staff report

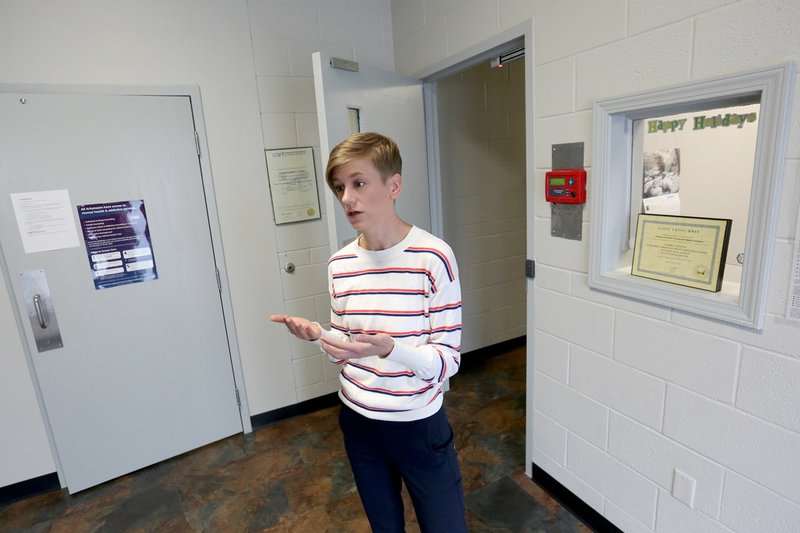

Kristen McAllister, director of the unit, said 163 patients have been admitted as of Friday since it opened in late June.

Police officers and mental health professionals from Ozark Guidance, an outpatient mental health center with clinics throughout the region, refer patients to the unit. The unit is an alternative to jail or the emergency room.

Ozark Guidance staff, including McAllister, operate the unit. Washington County spent $250,000 to renovate a former juvenile detention center for the unit, and the state has committed to pay the operating costs of the facility through June 2021.

Different worlds

Lt. Derek Wright of the Springdale Police Department described law enforcement and health professions as being "two completely different worlds" before the crisis stabilization unit.

Wright has worked for the department for 14 years.

Police officers typically took people with suspected mental illnesses to the emergency room in hopes of getting them transferred to a behavioral health facility rather than jail, he said.

"The emergency room is set up for medical care, not for behavioral health," Wright said.

Jessie Nelson, associate clinical director at Ozark Guidance, is among the mental health professionals who help teach officers about specific symptoms of various mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. What untrained officers may interpret as someone intentionally ignoring them may be involuntary behavior, she said.

Fayetteville police officers Scott O'Dell and Garrett Levine said at a recent meeting of a regional advocate group, Judicial Equality for Mental Illness, people with mental illnesses have been approaching police for help for a long time.

"It's been going on for decades. It's just that now we have somewhere to take them," Levine said.

Officers sometimes end up calling doctors or family members for people who come to the police station, O'Dell said.

Levine said most officers know dealing with people with mental health problems is an issue. However, officers in small towns may not get as many calls involving people experiencing mental crises, which is all the more reason for the crisis intervention training, he said.

Training

A state law enacted in 2017 requires police departments with more than 10 officers to have at least one officer trained in crisis intervention by attending a 40-hour course given over five days.

The goal is to train 20% of officers in each police force, said Sgt. Steve Linton of the Rogers Police Department.

About 30 officers from Fayetteville, Bella Vista, Little Flock, Springdale and other police departments took part in training at the Rogers Police Department in late October.

The goal is to teach officers how to de-escalate situations where someone is having a mental crisis and to divert people who haven't committed serious crimes away from jail, Wright said.

Mental crises can involve people who are talking about harming themselves or are delusional, for example.

Wright helped host the training. He said trained officers are more knowledgeable about the resources available to them, such as the crisis stabilization unit, and are more prepared to handle calls involving people with possible mental illnesses.

The officers tour the crisis unit, meet the director and hear from mental health professionals from Ozark Guidance. Officers learn how to persuade people to go to the unit, which only admits patients voluntarily.

When police get calls involving "petty nuisance crimes," such as loitering, public intoxication or trespassing, the police can talk with the suspects to learn if the crisis stabilization unit may be a good fit for them instead of arresting them, Wright said.

In one exercise, officers listened to a recording through earphones of different voices -- some shouting, some whispering phrases like "Shut up," "Do not touch that" or "You can do that" -- while they tried to converse with other officers. The goal was to give them a sense of what it's like for people with a mental illness such as schizophrenia to hear voices while an officer is trying to talk to them.

In another exercise, officers split into groups of five. One pretended to be a person having a mental crisis while the other officers acted as if they had taken the call. They asked the officer what had upset her, if there was a friend or family member they could call and if she had any weapons on her.

Linton, who also hosted the training, told the officers to avoid minimizing anyone's problems like saying "it's not like it's the end of the world" to people who may feel like what they're going through is the end of their world.

"It sounds like you're frustrated," may be better, for example, he said.

"Do your best to be empathetic," he said.

"On the same team"

About half of the referrals the crisis stabilization unit receives is from law enforcement, while the other half is from Ozark Guidance, McAllister said. Ozark Guidance does not have inpatient beds.

Staff members from Ozark Guidance meet with patients at the unit who may seek long-term outpatient treatment, she said. The idea is for the staff member to have background on the patients' case.

Most patients have both a mental illness and substance use problems, McAllister said. The goal is for them all to leave with an appointment for therapy or substance use treatment.

Wes Hamilton, 59, said he has stayed sober for the more than two months since leaving the unit. The staff made sure he had counseling appointments set up, and staff members have called to check on him a few times, he said.

Hamilton was referred to the Washington County Crisis Stabilization Unit after an emergency room visit. He made appointments with a therapist before resorting to the emergency room, but missed those appointments because he was too drunk to go, he said. During his stay at the unit, he went through a detoxification from a year of daily heavy drinking.

He also participated in group and individual therapy. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms such as shaking, sweating and not sleeping well, were "pretty rough," but the medication he was given made them safer and easier to handle, he said.

"What did people do before that place was open?" Hamilton said.

Dr. Danelle Richards, medical director for Northwest Health's emergency rooms, said she's glad the unit is open because it serves as another option for people who need immediate help.

"Not every patient needs to come to the emergency room," she said.

However, Richards said the police should continue to bring people to the emergency room when they appear to be heavily intoxicated or under the influence of drugs. The hospital needs to make sure they are not at risk of overdosing, especially if they've made suicide threats. The hospital keeps patients for 72 hours involuntarily in certain situations, such as suicide threats, Richards said.

Northwest Medical Center in Springdale is the only hospital in Northwest Arkansas that has an inpatient psychiatric unit. Springwoods Behavioral Health and Vantage Point Behavioral Health Hospital, both in Fayetteville, also have inpatient beds.

Wright said in the past, police officers would sometimes take people to the emergency room or call an ambulance for them when they were threatening to harm themselves. Patients would often then tell hospital staff they weren't really going to harm themselves and leave the hospital, leaving law enforcement and hospital staff with few options.

"That does not happen near as often," Wright said.

Wright said police are avoiding calling ambulances, which are costly to patients, unless a medical emergency warrants one.

Richards said she sees law enforcement and health professionals as partners.

"They're out on the streets. They identify these situations," she said.

The patients police bring to the unit are often people officers know because they have previously responded to calls involving them or they are homeless and on the streets. McAllister has had some patients leave the unit asking how they can contact the officers who brought them in to thank them.

"The biggest thing is just knowing that we're all on the same team," she said.

NW News on 12/29/2019