Questions linger over a 68-year-old Arkansas Supreme Court opinion that denied lawmakers the ability to alter constitutional amendments, after attempts to force a reconsideration of the ruling failed to gain traction during this year's legislative session.

Earlier this year, legal circles around the state Capitol began buzzing anew over the idea of the Legislature making tweaks -- or outright repeals -- of constitutional amendments, as a way to address issues that arose after last year's citizen-initiated amendment to expand casino gambling, said state Sen. Mark Johnson, R-Little Rock.

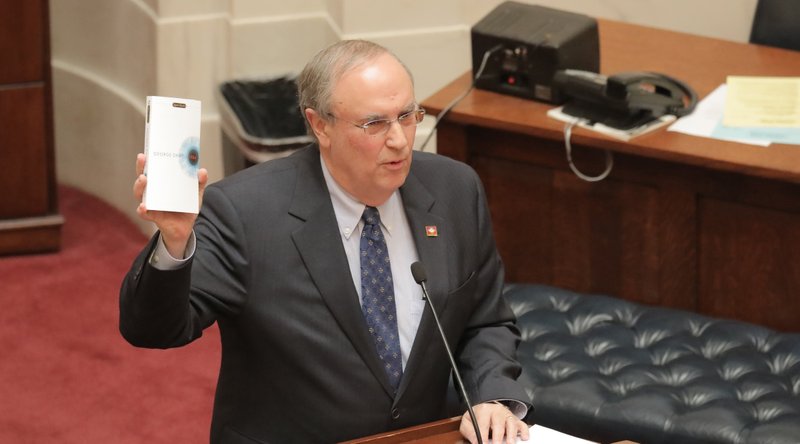

Johnson was one of three lawmakers to file legislation that openly contemplated the possibility that the current Supreme Court would overturn a long-standing precedent in the 1951 case Arkansas Game and Fish Commission v. Edgmon. That ruling effectively shut the door on lawmakers hoping to make their own changes to constitutional amendments.

Each of the bills -- which also sought to make changes to the casino gambling amendment -- failed to become law.

Johnson, while not an attorney, said the basis for his idea to challenge the long-standing court precedent came from "smart attorneys" who suggested that the current high court justices were taking a more literal look at the constitution than the justices were in 1951.

[RELATED: Complete Democrat-Gazette coverage of the Arkansas Legislature]

Others, however, cautioned against giving lawmakers greater power to override decisions made by voters.

Scott Trotter, a Little Rock attorney who has been involved in past litigation regarding constitutional amendments, said that overturning the court's precedent could open up any of the 27 amendments drafted by citizens -- including measures that legalized the lottery, medical marijuana and an expansion of casino gambling -- to changes or outright repeal by lawmakers.

"All of those issues might end up being debated if the Legislature decided it wanted to overrule an amendment by a two-thirds vote," Trotter said.

Article 5, Section 1, of the Arkansas Constitution states that "no measure approved by a vote of the people shall be amended or repealed by the General Assembly or by any city council, except upon a yea and nay vote on roll call of two-thirds of all the members." Looking at that language in 1951, a majority of the Supreme Court found it "inconceivable" that the purpose was to give the General Assembly the ability to repeal or make changes to constitutional amendments, according to the opinion written by Chief Justice Griffin Smith in the Edgmon case.

Since then, the power to alter the constitution has been solely vested in the voters (though some voter-approved amendments, such as the 2016 amendment to legalize medical marijuana, give lawmakers some leeway in making changes).

Johnson said the idea of revisiting the 1951 ruling came to him even before he was elected to the Senate last year. When he raised the idea to attorneys he knew, Johnson said he was rebuffed and told it was settled law.

Then, early last year, the Supreme Court overruled nearly 20 years of precedent in an entirely different matter, sovereign immunity, by taking a stricter approach in interpreting the constitution.

"Going back to those same smart attorneys who said 'no, no' ... they came back and said with this ruling, all bets are off," Johnson said.

The attorneys who spoke to Johnson could not be reached for comment Friday.

Lifting language from the Supreme Court's 2018 decision regarding sovereign immunity, Johnson included several paragraphs of legislative intent in his bill to change the casino amendment. His bill states, "An interpretation of the Arkansas Constitution [Article 5, Section 1] 'precisely as it reads,' clearly leads to the conclusion that the General Assembly may amend all measures, including constitutional amendments, by a two-thirds vote of each house."

The statement of intent behind Johnson's bill, Senate Bill 498, anticipated a legal challenge that would result in the Supreme Court overturning its decision.

The other two bills that mention the Edgmon ruling were both on setting up an election to see if voters in Pope County approved having a casino there. The bills were Senate Bill 404 and House Bill 1517 sponsored by Sen. Breanne Davis, R-Russellville, and Rep. Joe Cloud, R-Russellville.

It's not the first time lawmakers have contemplated passing legislation to set up such a challenge. During the 2009 session, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette previously reported, then-House Speaker Robbie Wills supported legislation that would have altered an amendment dealing with government bonds.

But instead of taking action themselves and setting up a Supreme Court challenge, the 2009 Legislature simply referred their proposed change to the voters, who approved the measure in the 2010 election.

Current House Speaker Matthew Shepherd, R-El Dorado, an attorney, said he agreed with Wills that the Legislature did have the authority to make changes to constitutional amendments, if such changes could be agreed upon by two-thirds of the members.

"The constitution has a provision that provides for the Legislature to make revisions," Shepherd said.

The speaker added, in reference to bills proposed during the session to alter the casino amendment, that there was a "difference of opinion" over the matter and he did not counsel other members as to his own legal interpretations.

The last time an attorney general weighed in on the matter was in 2001, when then-Attorney General Mark Pryor, a Democrat, was asked by state lawmakers to clarify whether the Legislature could vote to amend or repeal constitutional amendments.

"It is my opinion that the answer to your question is 'no,'" said the opinion drafted by Pryor's office and signed by Pryor.

A spokesman for the current attorney general, Leslie Rutledge, said she has not been asked to weigh in on the matter.

In any case, it will likely be at least two years before there is another opportunity to attempt a change in a constitutional amendment. The next legislative session, in 2020, will be on fiscal matters. The next regular session is scheduled to begin in January of 2021.

SundayMonday on 04/21/2019