"Childe Rowland" is an Anglo-Saxon fairy tale about a boy -- possibly the son of Guinevere -- who enlists the help of the wizard Merlin after his sister is abducted, apparently by fairies while playing games near a church. ("Childe" was a medieval term for an untested knight, not necessarily a child.) When Burd Ellen went to retrieve a ball Rowland had kicked over the church she took a counter-clockwise course, going "widdershins" (or "withershins"), a dangerous breach of protocol that landed her in Elfland, locked high in a "Dark Tower."

Rowland only takes up the quest to find his sister after his two older brothers try and fail to return from Elfland. He takes his father's sword, which has never been used in battle, with him. Merlin instructs Rowland that, until he finds his sister, he should chop off the head of anyone in Elfland who speaks to him and that he must not eat or drink while he is in the realm. So he kills a horseherd, a cowherd and a woman tending chickens. As she's dying, the woman tells him he should run around a certain hill three times widdershins, calling "Open door!" As he completed the third trip, a door opened in the hill and Rowland entered, finding a great hall, where his sister was being held, under the spell of the King of Elfland.

She told him he should not have come, for all who did would be held in the Dark Tower. Their brothers were being held there, and they were nearly dead.

Exhausted and hungry, Rowland momentarily forgot Merlin's warning, and asked his sister for food. She brought him a plate but at the last moment Merlin's word came back to him and he threw down the food. The King of Elfland rushed into the hall and Rowland beat him into submission with his father's sword. Rowland spared the King after he agreed to release Burd Ellen and her brothers. They traveled home together and none of them ever ran widdershins around the church again.

Like a lot of old legends, "Childe Rowland" might seem weird and strange to us, a long way to go to warn children of the dangers of nonconformity. But it had resonance, it's referenced in Shakespeare's King Lear when in Act Three Scene Four, Gloucester's rich and clueless son Edgar finds himself falsely accused of plotting his father's murder. So Edgar flees into the moors, disguising himself as a wandering beggar, a "Tom O' Bedlam." Feigning madness, he sings:

Childe Rowland to the dark tower came,

His word was still, 'Fie, foh, and fum,

I smell the blood of a British man

(Shakespeare was probably also lifting from or alluding to the story of "Jack the Giant Killer," which was likely written a few years before King Lear.)

And the reference in Lear inspired Robert Browning to write his 1855 "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came," a poem that investigates the problem of knowing what and whom to trust and the unreliability of one's senses and thoughts. It's about a knight on a quest he knows will end in failure and death but which his honor compels him to pursue.

Browning claimed the poem came to him in a dream and was written in a single day. There is evidence he worked on it for a couple of years. It's not a particularly difficult poem for the modern reader -- most of the words retain the same meaning and connotation they do today, but it's open to a lot of interpretations. Margaret Atwood has suggested the "Dark Tower" Browning alludes to is the poet himself, and his doomed quest is to write the poem. Stephen King made something altogether different of it.

. . .

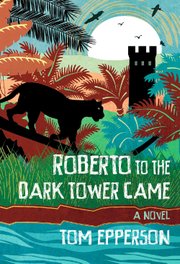

And the poem lends a title and epigraph to Tom Epperson's latest novel, Roberto to the Dark Tower Came (Meerkat Press, $26.95). Roberto is a lot like Epperson's two previous novels, 2008's The Kind One and 2012's Sailor, both cinematic hard-boiled crime novels that simultaneously revel in and subvert the conventions of the Los Angeles detective novel. But it's also more ambitious, a quest set in an unnamed (but in some ways recognizable) South American country. It's like Raymond Chandler and Joseph Conrad teamed up to write a thriller.

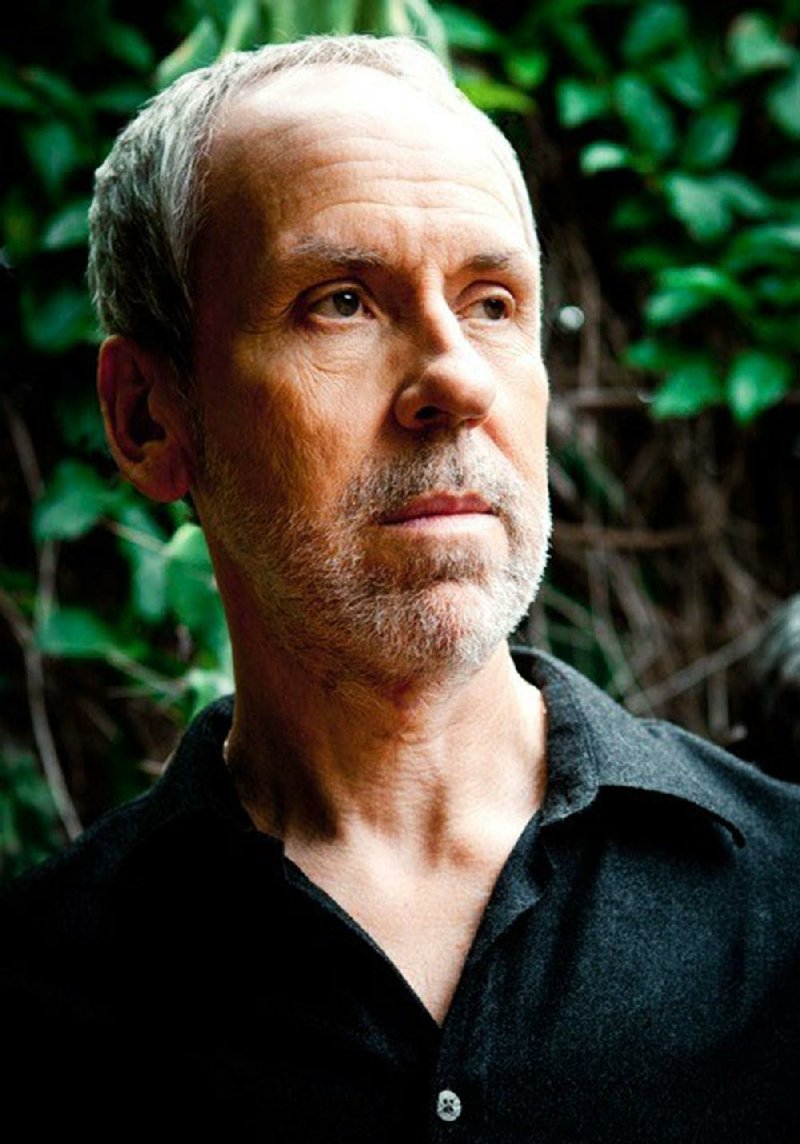

Around these parts, Epperson is best known as Billy Bob Thornton's childhood friend from Malvern and frequent screenwriting collaborator. Together they wrote One False Move (1992), the Robert Duvall-James Earl Jones racial identity drama A Family Thing (1996), The Gift (2000), the gritty HBO junkie thriller Don't Look Back, and 2012'sJayne Mansfield's Car. Epperson also wrote the script for 1997's A Gun, a Car, a Blonde with that film's director, his wife, Stefani Ames.

Unlike the protagonists of Epperson's previous novels, the title character isn't a quasi-criminal trying to escape a violent past. Roberto is a hotshot young journalist who has made a name for himself investigating government and military corruption and violence. He's doing his job too well for the shady forces that really run things. As the book begins, he's given notice that he has 10 days to leave the country.

So he resigns from his newspaper job and makes plans to move to Saint Lucia to be with his well-heeled girlfriend. There he'll write a book about his country. But before he goes, he comes across evidence of war crimes in a remote province. So -- reluctantly accompanied by his friend Daniel, a talented photographer battling his own demons -- Roberto journeys to the site of a massacre, a beautiful estate called El Encanto, to meet with rebels and investigate the Black Jaguars, a paramilitary group presumed responsible for the murder of civilians.

I recently talked with Epperson about the just-published book:

Q: The South American country in the book bears an obvious resemblance to Colombia, but also to '70s Brazil and Argentina. I'm wondering if there was a specific model and how you conducted your research.

A: The nameless South American country is based mostly on Colombia. My wife, Stefani, went to film school with Carlos Gaviria, a Colombian filmmaker, and he and his wife, Mariela, are among our best friends. I made two trips to Colombia with Stefani to research the book, with Carlos and Mariela acting as our guides. The first trip we spent in Bogota and surrounding areas. Bogota's high in the mountains and is a very different world from the Amazon rain forest to the south, which is where I went with Carlos on our second trip. The wives had no desire to visit the jungle and stayed in Bogota.

Roberto's country is also based on other Latin American countries, especially Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Peru, Chile and Argentina. I read tons of books about those countries. I've been interested in Latin American culture, and especially its dark side, ever since my 20s. One of my many plans from the time which never came to fruition was to journey to Nicaragua and join the Sandinista guerrillas in their fight against the American-supported dictator Somoza. I remember during that time having frequent, terrifying atrocity dreams, always set in some nameless Latin American country. It was almost as if I had some kind of psychic, possibly reincarnational connection to what was happening in Latin America, and I've never lost that feeling.

Q: Tell me about the rain forest.

A: On our second trip to Colombia I flew with Carlos to Leticia, which is at the southern tip of the country on the Amazon River where Colombia, Brazil and Peru meet. It's an isolated, dismal, dirty town (in my novel it became Tarapaca), and Carlos and I quickly escaped into the rain forest in Peru. I thought having grown up in Arkansas and endured its long hot summers I would be prepared for the jungle, but I found it shockingly hot and humid in the beginning and felt like I could hardly breathe. But I got used to it, and the days and nights I spent in the jungle I count now as among the very best of my life.

What did I like? The rivers, the trees, the plants, the monkeys, the fish, the birds, the pink porpoises, and the knowledge that at every moment a jaguar might be watching you from some hidden place with its golden eyes.

Not as a part of my research, but just out of curiosity, I sought out a shaman to give me ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic drug native to the Amazon. Carlos and I along with Tomas, our young Indian guide (he became Roque in the book), walked about an hour through a dark swamp under towering trees before we found him, just as the sun was going down. I'd like to say I had magical life-changing visions of conversing with giant anacondas and being changed into a jaguar and running through the jungle, but the foul brew made me about as sick as I've ever been in my life and except for seeing a few streaks of colored light I didn't have any visions, and I was stuck there all night till the sun rose and we could slog back out of the swamp. Probably the longest night I've ever had.

Q: I thought about Conrad's Heart of Darkness while I was reading the book. Did you think about it while writing it? I also thought about Roberto in relation to Browning's poem "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came" and the inevitability of failure. Roberto is like Roland in that he knows the quest is likely doomed yet he persists because, like Roland, he has to. He picks up his slughorn and blows.

A: I absolutely thought of Heart of Darkness while writing the book. I haven't read it since college but it's still stuck in my head and heart: the archetypal journey-up-a-river-into-a-dark-and-perilous-jungle story. Something timeless and myth-like about it.

And you're spot on in regards to "Childe Roland." Couldn't express it any better. ... It's not uncommon for fictional heroes to die, but there's almost always some victory in their death, some consolation; e.g., Robert Jordan blows up the bridge in Spain and holds off the fascists long enough for his beloved Maria to make her escape.

There's a foreshadowing of Roberto's fate on Page 95. Roberto asks Gloria if she thought her handsome, dashing, and dead guerrilla lover Luis Velasquez was afraid to die. She replied: "I remember something he said to me once: 'Here's the thing, Gloria. You have to decide ahead of time that even if the worst happens, if your side loses and you're caught by criminal lunatics and you're tortured and killed ... it was worth it anyway.' And then he repeated it, like it had already happened: 'It was worth it anyway.'"

Q: Is there a real-world analog for Roberto? Or is he a composite of people you've either known or read about? I think one of the most hazardous jobs in the world might to be an investigative reporter in Latin America.

A: The genesis of Roberto, both the character and the book, came when I read an article 11 years ago in the Los Angeles Times about a journalist in Somalia named Abukar who'd received an anonymous threat: Leave the country or be killed. I knew immediately that was a great beginning for a novel and that I would change the setting to South America. The character of Roberto isn't based on anyone in particular. The world's full of brave journalists who pursue the truth at the risk of their lives. There are no people I admire more. If I had it to do all over again I think I'd like to be a journalist like Roberto.

Q: Daniel is also a vivid, tragic character. His motivations seem very complex and very human. Where does he come from?

A: I have a couple of friends, one American and one Colombian, who share certain characteristics with Daniel; don't know if they'll recognize themselves in him if they ever read the book. Daniel is a victim of governmental repression and torture and has had his life shattered and is now doing the best he can to pick up the pieces and go on.

Q: Without giving away the ending, did you consider a happier option? If, as seems possible and maybe even likely, the book is adapted into a movie, would you be OK with the ending being changed?

A: The ending has always been the ending, from the moment I read that story in the Times. The ending won't change in the movie if I have anything to say about it.

We've started to send the book out to producers over the last few weeks. Naturally I would love it to be a movie or, better yet, a limited TV series. It would be nice to have an unhurried six or eight hours to tell the story.

Q: Given your background, a film version seems natural. You write in a very cinematic fashion, to the point of physically describing your characters in more detail than some writers might. I'm wondering about your process, whether the story comes to you fully realized and you work to fill in the details or whether it reveals itself slowly as you write. How do you do it?

A: What I would call my vision for a book or screenplay comes to me very quickly. I get the beginning and the ending first. If you looked at my (extensive) notes for Roberto, you would see in the first page or two the opening words of the book and then the closing words. After that it's just a matter of filling in everything that comes between the first page and the last. I have a general idea of where I'm going but don't know exactly what I'm going to write until I get there, and I always reserve the right to make major changes on the fly.

To watch a video trailer for Roberto to the Dark Tower Came, go to http://meerkatpress.com/books/roberto-to-the-dark-tower-came/ or our blood, dirt & angels blog.

Email:

www.blooddirtangels.com

Style on 06/03/2018