Change was afoot in the third week of December 1918, and it bumbled around in Arkansas, knocking stuff down.

Results from the Dec. 14 special election increasingly suggested that the proposed new state Constitution lawmakers had labored over all year had failed to pass, undone by flu, cold and low turnout — and disapproval, of course. I say "increasingly" because election results 100 years ago took days or weeks to make themselves known.

With the end of the war, the end of the Camp Pike economic boom was at hand. Although dozens of invalids began to arrive for convalescence, the camp discharged hundreds of soldiers a day. Family men and sons with homes to go to immediately piled onto trains and left central Arkansas. No-accounts lingered in an unsavory fashion.

Even the animals started to leave: In late December the camp auctioned 5,000 horses and mules at its remount station, which had trained animals for the cavalry — hence the name of today's Remount Road in North Little Rock.

Townspeople would have known to expect reductions at Camp. But the War Department also stopped construction and production at the 80 percent-complete picric acid plant in Factoria, a 700-acre section just east of Little Rock including today's Adams Field. The plant made acids for explosives. It had been plagued by meningitis and flu, but it employed hundreds.

A thousand Puerto Ricans decided it was time to go home.

In the middle of this disruption, of thousands in transit and incomes upended, canvassers from Polk's Southern Directory Co., which planned to publish a city directory, began knocking on doors and asking whether residents were permanent.

Imagine being asked that question if you hadn't made up your mind yet.

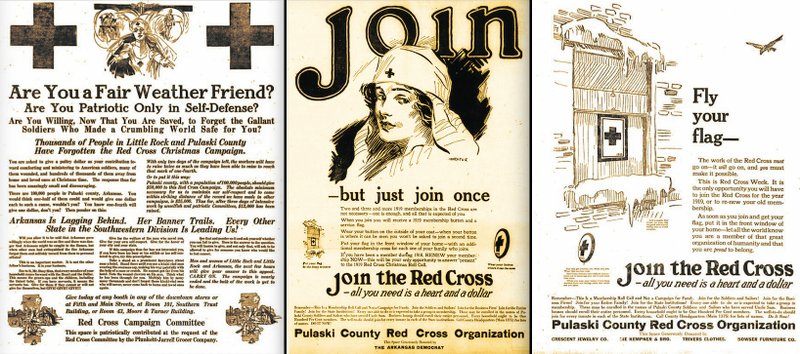

Confused investors somehow got the idea their Liberty Bonds were worthless now, and sharp shopkeepers offered to take them as cash at face value. But meanwhile, yet another new patriotic funding campaign had begun, this one asking everybody to give the Red Cross $1 in exchange for a lapel pin. It wasn't making much headway.

And then — and then — the threatening cabin appeared in Echo Valley behind Fourche Mountain (aka Granite Mountain).

The "Hut of Mystery," as the Arkansas Gazette dubbed it, was triangular but unusually well made, using oak poles.

Surrounded by a crude pole fence covered in brush, the hut was reported to be impossible to detect, even from a short distance away — and yet it had been detected.

Two white men and a negro were said to have built the hut last summer. One of the men was seen in the neighborhood of the hut Sunday. Two of the men were in uniform and it is believed that they were deserters.

This report appeared on the front pages of the Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat on Dec. 18, 1918. The Gazette hit porches in the morning, the Democrat in the afternoon. In the morning, the Hut of Mystery was still mysterious even after four heavily armed deputy sheriffs, a game warden and an internal revenue officer approached and found it deserted.

It took their combined force to get past the chain and padlock on the door.

The hut, the triangular sides of which were eight by six by six feet, had a loft which contained peep holes from which the occupants might look in every direction.

The loft held a mattress stuffed with pine needles. Investigators found blank shells from an Army rifle and remnants of food.

On the door was a placard bearing the words, "No trespassing; government property. Game warden."

A note was found in the hut, part of which was written in French. It advised the person to whom it was addressed that it would be advisable to "beat it."

J.W. Lumpkin, revenuer, accompanied the deputies in case it contained a bootlegger's stash.

By afternoon, the Democrat had more information.

The placard that read "No trespassing" also bore words on its obverse: "Don't boil the coffee inside the hut; you might set the hut afire."

But there was more. That morning one Jean Laville, a youth of the city but of French extraction, living at 107 E. 22 St., had appeared at the sheriff's office to confess everything he knew about the hut, including who built it and who had been hiding out there.

It was he, Jean Laville, and two friends. They had erected the cabin in the spring and were in the habit of spending Saturdays in the little structure, using it as their secret headquarters ... for boyish hunting expeditions and weekend wilderness adventures.

They were Boy Scouts.

■ ■ ■

Among soldiers shown the door at Camp Pike were graduates of the school for Army cooks and bakers. We can gather from the tone taken by the Dec. 20 Democrat that training men in kitchen arts was considered a humorous novelty. But without ladies on battlefields, somebody needed to make the mess.

This school, about the biggest in the world, has graduated 177 bakers, 899 mess sergeants, 840 first and 1,370 second cooks since its establishment in August, 1916.

The paper joked that graduates had such knowledge that their wives would be able to take vacations from the daily grind of cooking. But, the reporter said, the men were vowing to keep their skills a secret.

■ ■ ■

Not every soldier was ready for discharge, and watching buddies hightail it could be depressing.

Concerned for morale, the secretaries of the War Camp Community Service urged residents to open their homes:

"The camp is breaking up. Every day the men who must remain see hundreds departing for their homes, to family, friends and sweethearts.

"We respectfully urge that you invite at least one soldier to enjoy Christmas or New Year's in your home. Let us not forget the men who have done so much, or stood ready to do all, for our country and all humanity."

The appeal didn't mention the entertainment these men might provide, but newspapers were speckled with written accounts from discharged "boys," many amusing. And former soldiers were giving "thrilling" speeches.

The image of a grateful soldier spinning his personal tale amid the lemon glow of candlelight around a host family's table was in my mind when I ran across a different angle in the Dec. 20, 1918, Democrat. The reporter interviewed wounded soldiers back from overseas and at Camp to convalesce. One wore a ring from a German major and a belt from a machine gunner, both of whom he had bayoneted.

Another, unnamed, told how he and a buddy had thrust bayonets through German officers, one by one.

They ran across a German major who was alone in a trench. They ordered him to surrender, which the major refused to do because the boys were privates. He stated he would surrender to an American officer.

So they stabbed him in the throat. Probably his remains were still in that trench, the soldier said.

I relish the humor in old newspaper stories. It was part of that war and surely made many hardships bearable. But I also should think about what that war mostly was, and funny it was not.

Email:

Style on 12/17/2018