"Incomplete understanding of our parents' lives is not a condition of their lives. Only ours. If anything, to realize you know less than all is respectful, since children narrow the frame of everything they're a part of. Whereas being ignorant or only able to speculate about another's life frees that life to be more what it truly was."

-- Richard Ford, Between Them (2017)

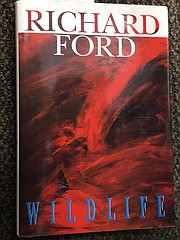

There are some questions that are not worth asking. If Richard Ford did not approve of the movie that Paul Dano, actor-turned-first-time director, had made of Ford's 1990 novel Wildlife, the author would not be doing interviews to promote the movie.

No one would have thought anything about that. Though most movies are born on paper or its electronic equivalent with people coding images in their heads into words so that other people might decode them into their own mental pictures, we tend to receive movies as something like apprehended life. Which is to say it is life heightened and compressed, with most of the boring parts cut out (though sometimes left in for contrast or to advertise the director's commitment to verisimilitude), but not exactly something acted out and choreographed. One measure of an actor's skill is his ability to convince us he's not acting.

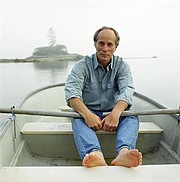

"I told Paul my book is my book," says Ford, on the phone from his home in Billings, Mont. "Your movie must be your movie. The best thing I could do for him was to give him permission to leave the book behind."

And Dano does, in some small but pertinent ways, diverge from Ford's novel, although the writer isn't completely sure exactly what was retained and what was invented. He hasn't reread his novel, because rereading one's own book seems a curious thing for an author to do. Readers can revisit books, but for a writer a book is something to be gotten out of one's system, something to be exorcised. Maybe put a copy in the bookcase and keep a box of them in your office or garage, but a book is a kind of tomb. You'd only exhume it for extremely good reasons.

On the other hand, the spirit -- the theme -- may never be done with you.

Unlike Ford, I have reread Wildlife recently. I saw Dano's film first, which -- and Ford agrees -- is the best thing, the only way to be fair to the film. So if you have not read Wildlife or have not read it for a long time, wait until after the movie to do so. I know that in the book the protagonist is 16, not 14 as he is in the movie. I know that my favorite line from the book -- "We won't get rich working for rich men but we might get lucky hanging around them" -- doesn't appear in the movie.

In the book it is Jerry, the father of 16-year-old Joe Brinson, who speaks that line. It is 1960, and Jerry, on the rebound from unspecified troubles in Idaho, has taken a job as a golf pro at the country club in Great Falls, Mont. At the time he says it, he's optimistic. He has moved his family -- wife Jeanette and Joe -- there, to the sort of buff brick ranch house that signifies socially mobile Americanism, or used to. The sort of house no one lives in for long, from which people either trade up or move down. Jerry thinks he can get lucky with these rich men, who pay him to improve their game and lose $2 Nassau bets to him on the weekends.

The Jerry in the movie, played by Jake Gyllenhaal, is not quite the same character as the character who appears in Ford's book. Gyllenhaal's Jerry is not as self-assured and seems to be finding out things about himself as he goes along. When we meet this Jerry, he's literally kneeling before the members of his club, cleaning their golf spikes with a brush. And when he is (spoiler alert, though this is really where the story begins) dismissed by the club president, this Jerry accepts it with a serf-like meekness.

In the book, Jerry cleans all of the cash out of the pro shop after he's fired. Then he looks around "at the clubs and the leather bags and shoes, the sweaters and clothes in glass cases ... [a]ll things that cost a lot of money, things my father liked." He tells his son to take anything he wants.

When Joe says he doesn't want anything, his father tells him:

"You've got good character, that's your problem. Not that it's much of a problem."

He explains to his son that he was fired because he was suspected of stealing a member's wallet.

"I'm not a stealer," Jerry tells his son. "Do you know it? That's not me."

And Joe, who has just seen his father taking money from the register, tells him he believes him. And then he tells us: "I thought I was more likely to be a stealer than he was, and I wasn't one either."

Dano's 14-year-old Joe, played by Ed Oxenbould, isn't as alert to the world as Ford's 16-year-old is -- and he's neither a perfect audience surrogate -- there are scenes in the movie he does not witness -- nor an entirely reliable narrator. Ford insists his Joe is "100 percent reliable, because he tells us there are things he doesn't know."

. . .

It's wrong to assume that any part of either Wildlife is autobiographic. If you want to know about Ford's parents, read his lovely memoir Between Them: Remembering My Parents, which was published last year. Ford's father, Parker, died when the writer was 16, in the same year as Wildlife is set. He grew up in Arkansas and Mississippi, not Great Falls. His father was a traveling salesman who liked to be happy and made his family's life "as festive as life can possibly be."

Ford says -- in his gently swinging accent that, at 74, still evinces Jackson and Little Rock -- he has done so over the years.

"I certainly think we have histories. And based on them we can purport to have characters -- invent or allege character, in a sense," he told The Paris Review in 1996. And coming to terms with the fallibility and humanity of one's parents has long been a theme in Ford's work.

You can find another Brinson family living in Great Falls in the story "Optimists" in his 1987 short story collection Rock Springs. It's 1959 and the narrator, Frank, who is 15, tells a story about how his father, Roy, came to accidentally kill a man, with whom his mother, Dorothy, may have had an affair, and goes to prison for five months. After Roy gets out he goes back to his job as a railroad switchman, the couple separate and Dorothy moves out. Frank turns 16, lies about his age and joins the Army.

Roy "fell off the railroad, divorced my mother .... Drinking was involved in that, and gambling, embezzling money, even carrying a pistol," Frank remembers. "I was apart from all of it. And when you are the age I was then, and loose on the world and alone, you can get along better than at almost any other time, because it's a novelty, and you can act for what you want, and you can think that being alone will not last forever."

In his 1987 essay "My Mother, In Memory," which constitutes roughly half of Between Them, Ford writes, "From almost the first I felt that my father's death surrendered to me almost as much as it took away. It gave me my life to live by my own designs, gave me my own decisions. A boy could do worse than to lose his father -- a good father, at that -- just when the world begins to display itself all around him."

In Wildlife, Jerry leaves Great Falls and his family to fight the wildfires that rage ceaselessly in the mountains.

"I saw a bear that caught on fire," Jerry tells his son on the telephone. '"You wouldn't have believed it. It just blew up around him in one instant. A live bear in a hemlock tree. I swear. He hit the ground squalling. It was like balled lightning."

(Something I don't mention to Ford though it is in my notes: I saw that image realized in a movie a couple of years ago, in the very beginning of Only the Brave, when a computer-made image of a flaming bear runs through the woods, through Josh Brolin's nightmare. I thought of Wildlife then. I didn't know they were making a movie of the book.)

Left behind, Jeanette (played brilliantly by Carey Mulligan in the movie) is left to economize. Eventually she takes up with one of those rich men Jerry had hoped to get lucky hanging around, a limping racist (though not so overtly so in the movie) named Warren Miller. Joe witnesses his mother's foibles, and helps out by quitting football (which he never really liked anyway) and working after school.

Like Dorothy in "Optimists," Jeanette is a swimmer. She leaves the family. In the book she eventually comes back:

"In a while she and my father found a way to settle the difficulties that had been between them. And though they both may have felt that something had died between them, something they may not have even been aware of until it was gone and disappeared from both of their lives forever, they must've felt -- both of them -- that there was something of themselves, something important, that they could not live at all in any other way but by their being together, much as they had been before. I do not know exactly what that something was. But that is how our life resumed after then, for the little time that I was at home. And for many years after that. They lived together -- that was their life -- and alone. And God knows there is still much to it that I myself, their only son, cannot fully claim to understand."

. . .

Ford says he mainly tried to stay out of the way while Dano -- and Zoe Kazan, the actor who is Dano's girlfriend and co-screenwriter -- made their movie. But Ford has talked to Dano about it, and a couple of times he has complimented the director on a line, only to be told that it's in the book.

Wildlife is a fine novel, and Dano has made it into a very good movie, probably one of the best of this year. But not everyone thought that much of the book when it was published, the reviews were middling. (In The New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt was, as he could be, particularly nasty.) Ford was mildly surprised by the reception, and is gratified that it resonated with a few people, including Dano and Kazan.

It is difficult to understand exactly how the filmmakers, now in their mid-30s, were able to so completely conjure a period they never experienced. The year 1960 must be as remote to them as ancient Rome, yet they managed to make a movie that feels right to people who lived in those days. Ford is similarly impressed by their youth -- he was 42 when The Sportswriter made him as famous as literary novelists get anymore -- and their seriousness of purpose. They are "real artists," he says.

And he seems not to be bothered by the fact their art, their movie, will naturally become what people default to when someone mentions Wildlife.

It's OK. Ford negotiated a fair deal -- "I didn't hold them up or anything" -- and avoided becoming an on-set nuisance. His part in the collaboration is solid. And he got paid, which, for a writer, is kind of important.

So maybe it doesn't matter more people will probably see the movie in a weekend than ever read the book.

Ford has already seen it five times.

Email:

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 12/02/2018