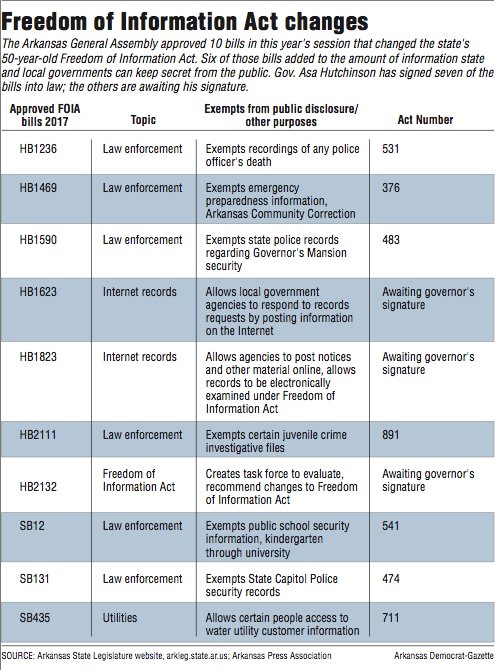

Before Arkansas lawmakers left Little Rock on Monday, they approved at least 10 amendments to the state's 50-year-old Freedom of Information Act.

Three prevent the public from learning security information that has been available for years about agencies such as the State Capitol Police, public schools and universities, and the Governor's Mansion.

Arkansas Freedom of Information Act experts and watchdogs say they worry how far the new secrecy will extend.

Security-records closures in some cases "were not bad ideas. Unfortunately, the bills went way too far by closing 'records and other information," said Arkansas Press Association Executive Director Tom Larimer.

That phrase could be broadly interpreted, he said, to include "just about anything" pertaining to the agencies. His group opposed all three bills.

"I don't think there is any doubt the 'security' bills passed in this session will have the most impact on the FOIA going forward," Larimer said.

Law professor and Freedom of Information Act textbook author Robert Steinbuch points to one of those new laws -- Senate Bill 131, now Act 474 -- that exempts disclosure of security records of the State Capitol Police.

Steinbuch sees the language as "somewhat too general" with "the potential to sweep up records the legislators likely didn't contemplate."

Sen. Gary Stubblefield, R-Branch, sponsored two of the security bills, including the Capitol Police exemption.

He told lawmakers they were designed to keep criminals from requesting security plans to plot an attack.

Chris Powell, spokesman for the Arkansas secretary of state's office that oversees the Capitol Police, said he was frustrated that some news reports had said the bill could extend further, such as restricting officers' pay information. That's not true, Powell said.

Records requests by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette last week, however, suggest the new law opens debate over what an agency is permitted to keep secret for security reasons, and what taxpayers have a right to know.

Asked if Act 474 would allow the public to obtain a copy of a Capitol Police lockdown plan, Powell said that's the kind of record the new law shields. His agency wouldn't provide it.

Asked whether the public could learn how many officers make up the Capitol Police force -- information that might be considered important for security, but necessary to examine an agency's budget -- Powell sent an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter to a state government website. Transparency.Arkansas.gov lists state employees, their titles and other information.

When the reporter asked Powell to verify a count of about 22 Capitol Police officers, he replied that was "approximately correct, and I understand this is public information."

"However," Powell wrote in an email, "I don't think that widely publishing the number of security personnel guarding a vital government facility is particularly helpful to the security of that facility."

Arkansas' Freedom of Information Act, Arkansas Code Annotated 25-19-101, requires state and local governments to disclose most records of their operations upon request from any member of the public.

When someone asks how much his town pays the mayor, Arkansas' public-records law makes it a crime for town record keepers to refuse. When a newspaper reporter asks for a university chancellor's emails regarding a head football coach, school officials have to hand them over or risk jail. The act also contains exemptions.

Arkansas' Freedom of Information Act is "a very good law to begin with," said Steinbuch, a professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock's W.H. Bowen School of Law.

He doesn't oppose "narrowly crafted, well-thought-out exemptions," he said.

He pointed to House Bill 1236, now law as Act 531, that exempts public disclosure of audio and video recordings of a police officer's death. That amendment is narrowly written and unlikely to be abused, Steinbuch said.

Generally, "I am hesitant in wanting to change what is an outstanding law, due to the risk of unforeseen consequences," he said. "The danger with a tweak is not the tweak itself, but poking enough little holes into the FOIA that it eventually starts to fall apart."

In addition to exceptions for security and law enforcement agencies this legislative session, other changes to the law include at least two related to Internet records.

House Bill 1623 allows local governments to respond to a records request by pointing to information posted online, unless the requester specifies a different record format. State agencies already are permitted to do so.

Steinbuch said the Internet-records amendments don't change government agencies' responsibility to provide specific information that's usable.

If the requested records are posted separately and precisely online, "it seems perfectly appropriate to direct" the public there, he said.

But if agencies are dumping "vast amounts of documents that are not readily searchable, and the agency says, 'It's in there somewhere,' -- that runs counter to the intentions of those who drafted the FOIA," Steinbuch said.

Some good news this legislative session, Steinbuch added, is that two bills that he and others said would have seriously damaged the Freedom of Information Act didn't pass.

Senate Bill 373, to exempt from public disclosure records of attorney-client communication, and House Bill 1622, to extend the time period government agencies have to answer records requests "were bad on their face," he said.

Those bills would have allowed government officials to hide vast numbers of records under an attorney-client privilege claim, and delay indefinitely providing records to the public, Steinbuch said.

SundayMonday on 04/09/2017