I became a Warren Zevon fan the way a lot of people did -- I liked his 1978 single "Werewolves of London," so I bought the album Excitable Boy and found that there was more to him than the well-crafted novelty single suggested. So I bought 1976's Warren Zevon, which turned out to be one of the most important purchases of my life.

Warren Zevon was a tough and snarly record in which the self-aware poseur still managed to dredge up deep feelings. People make fun of "Hasten Down the Wind" and I understand why (especially if they've only heard Linda Ronstadt's version, which is lovely, but c'mon), but it married an earnest, seeking intelligence to heartfelt emotion. Plus it was immaculately produced by Jackson Browne. I don't think there has ever been a better album to come out of Southern California. If you want to know what the '70s were like, listen to Warren Zevon.

At the time I didn't know much about Zevon, that he was an old studio hand who'd been the musical director for the Everly Brothers, a crack jingle writer and a session musician. (He'd also roomed for a while with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks.) I didn't know he'd cut his teeth in a boy-girl folk duo with a friend from high school; that they'd styled themselves as lyme and cybelle, affecting the lower-case styling of the poet e e cummings. (Who in real life signed his name "E.E. Cummings," saving the typographical playfulness for the page.)

I made the connection between Zevon and Cummings as soon as I heard "Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner," about a Norwegian mercenary who fought in the Kisangani Mutinies that followed the Congo crisis and the Nigerian civil war in the late '60s. The song suggests that Roland's proficiency with the Thompson sub-machine gun brought him to the attention of the CIA, which presumably employed him as an asset before having him murdered by a fellow mercenary, Van Owen.

After Van Owen blows off his head, Roland becomes a stalking phantom, the "headless Thompson gunner" seeking revenge on his murderer and former handlers. This vendetta takes him on a tour of '70s trouble spots -- "Ireland, Lebanon, Palestine, and Berkeley" where:

"Patty Hearst

heard the burst

of Roland's Thompson gun

and bought it."

Compare that final line -- Zevon performs it as rendered -- to the end of what is probably Cummings' best-known poem "Buffalo Bill's" which ends:

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

how do you like your blueeyed boy

Mister Death

I heard "Roland" and I thought of "Buffalo Bill's" -- and something clicked into place about how light entertainment could work in the same ways as deep art. Zevon had transformed his amusingly detailed ghost into a comment on the viral nature of violence, just as Cummings had used the death of a popular Western icon as a means of saying something about the ephemeral nature of existence. Tumblers clicked in my 19-year-old brain.

Zevon's bringing Patty Hearst onstage at the end of the song was a bravado move, a little grace note that changed the way we received the entire narrative. It wasn't a simple credibility-borrowing name check like a lot of the shout-outs that mark a lot of today's pop music. It wasn't a boast or invitation to beef. It simply grounded the myth in near current reality.

Hearst, the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst -- the man Orson Welles made Citizen Kane about -- was kidnapped from her Berkeley apartment on Feb. 4, 1974, by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a small radical group of vague motives and confused politics headed by an unreliable fugitive from justice named Donald DeFreeze. During the kidnapping, Hearst's fiance and former math tutor Steven Weed was beaten but managed to escape through the backyard. Before he left, he'd reportedly told the kidnappers to "take anything they wanted."

They did. They took Hearst and probably turned her into the urban guerrilla Tania, re-naming her after Che Guevara's lover Tania Burke. She participated in the robbery of Hibernia Bank in San Francisco, a target chosen specifically for the security cameras that provided the world with the icon shots of the tiny heiress brandishing a cut-down M1 carbine that the SLA had converted into a fully automatic weapon.

By the time she was captured 19 months later, most of her SLA colleagues and an innocent bank customer were dead. At first she seemed unrepentant, but she soon recanted, saying that she was fearful for her life the entire time she was with the SLA. At her trial, her attorney, F. Lee Bailey, argued that she had been "coercively persuaded" into committing crimes while in the group's custody, and three mental health experts supported the theory. She had lost 28 pounds during her time with the group, and the famous clinical psychologist and cult researcher Margaret Singer testified, as many as 40 IQ points. Singer described her as "a low-IQ, low-affect zombie."

Still, on March 20, 1976, Hearst was convicted of bank robbery and sentenced to 35 years in prison; the sentence was reduced to seven years at the final sentence hearing. She served 22 months before President Jimmy Carter commuted her sentence in 1979. In 2001-- on his last day in office -- President Bill Clinton, acting on a request from Carter, granted her a full pardon. She laid low through most of the '80s but emerged in the '90s as a kind of low-grade celebrity, appearing in John Waters films (and sub-John Waters films like 1996's Bio-Dome). She's known in dog show circles as the co-owner of a champion shih tzu.

...

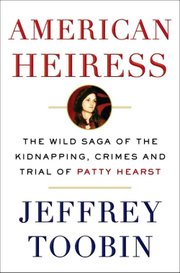

Jeffrey Toobin's new book on Hearst and the aftermath of her abduction, American Heiress (Doubleday, $28.95), seems less forgiving of Hearst than America at large has been. Maybe that's partly due to her refusal to be interviewed by Toobin. She published her own book about the case in the early '80s and since then has generally refused to talk about it.

Toobin attempts to make a case for Hearst as an exemplar of white rich privilege. That's probably right, at least in the case of the presidential actions taken on her behalf. Had she not been a Hearst, she certainly would never have been extended these courtesies. But had she not been a Hearst, she wouldn't have been a target for kidnapping at all. He suggests she was an opportunistic survivor who may have been enticed by the prospect of radical chic/criminal glamour rather than frightened into submission.

No one should be surprised if it wasn't a bit of both. As Toobin reports, in Hearst's first day in jail she was writing to her lover Steven Soliah "there will be a revolution in Amerikkka and we'll be helping to make it." A few weeks later she's asking her sister to provide her with makeup for her trial.

"As she weighed her future, Patricia chose between a world where people went skiing in the Alps and one where they ate horse meat and slept in crawl spaces," Toobin writes. But what she was really choosing was between the Alps and prison.

What Toobin does very well in his book, aside from providing a tragi-comic account of how Bailey mucked up her defense and providing a template for a cinematic treatment of the Hearst case, is to remind us how wild and scary the '70s sometimes were. In the years after Manson and Watergate, the dream of a hippie love-based revolution had died, but other forces were afoot. Toobin points out that in the early and mid-'70s there were about 2,000 bombings a year in the United States -- domestic terrorism was a potent force. There was a real sense that the center couldn't hold, that armed conflict between the police and discrete groups of disaffected Americans was inevitable.

Here's how Weed, Hearst's erstwhile fiance, who was widely written off as an ineffectual cuckold after the kidnapping, described the scene in Berkeley when he and Patricia (originally only her father, Randy, was allowed to call her Patty; the diminutive entered the public consciousness when her father spoke before TV cameras after she was taken) first moved there. In his 1976 book, My Search for Patty Hearst, Weed wrote:

"The radical leaders of the Sixties ... were no longer in Berkeley ... As for the masses of angry students that once gathered around the loudspeakers, raising their fists in militant salutes, many were now into communal living up-country, displaying their handmade hookahs down on Telegraph, meditating on the teachings of Zen, Jesus Christ, or ... holding down their straight jobs ... just doing their thing.

"But there was something else going on, a dark underside to the Berkeley scene that Patty and I were not aware of, or at least a side that was convenient to ignore. There were the latecomers -- the embittered Vietnam vets, the angry young women, the drifters and dropouts who had come from all over because they had heard that Berkeley was the place to get your head together and work for the revolution, 'funky Berkeley revolution,' as Eldridge Cleaver had called it. 'Death to the fascist insect that preys upon the life of the people,' he had said. But after swatting flies in Algeria for two years, Cleaver had moved to Paris, and now he wanted to come home again ... there was little talk of armed struggle, fighting in the streets and revolution. Now it was 'progressive legislation,' food programs, lecture circuits, and [Bobby] Seale for mayor. To those who had come to Berkeley to struggle and fight, this was counterrevolutionary. It was copping out, compromising with the pigs. The time had come for action, not talk ...."

The SLA was drawn from this late-coming remnant. They were not much older than I was when I first heard Warren Zevon, while Hearst was still in prison. America was a different place then, a crazy place of curdled dreams. A place where anyone -- even a petite rich girl with a boarding school accent -- could catch that virus Zevon sang about so often and so well.

Email:

pmartin@arkansas online.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 09/11/2016