LITTLE ROCK — “This is hard country to stay alive in.”

— Bob Dylan, “Narrow Way”

There’s no question Bob Dylan’s voice has changed a lot over the years. He arrived with an affected version of an Oklahoma drawl, an homage to Woody Guthrie informed by gutbucket blues and quickly transitioned into the quicksilver snarl of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, the warm country croon of Nashville Skyline and the raging prophet of “Idiot Wind.”

Dylan was always an idiosyncratic singer, a master of weird wheezy phrasings, willing to murder all prettiness for the sake of the song. Don McLean’s memorable phrase notwithstanding, Dylan never sang “with a voice that came from you and me.”

People can disagree on the merits of that voice — some said he sounded like a cow with its leg caught in a fence — but in the mid-1970s, Dylan was singing with uncommon power and authority.

Something happened between the release of Desire in 1975 and Street Legal in 1978. Some believe Dylan seriously injured his voice wailing nightly in the Rolling Thunder Revue. After that, he has treated us to a parade of voices, whines and rumbles, fricative consonants and glottal stops. Part of this might be the restless exploration of an artist who answers to no one but his own muse, but at least some of it must be due to the rescinding of his gifts. Dylan can no more sing the way he used to than he can write the way he used to, and it would be ridiculous to try.

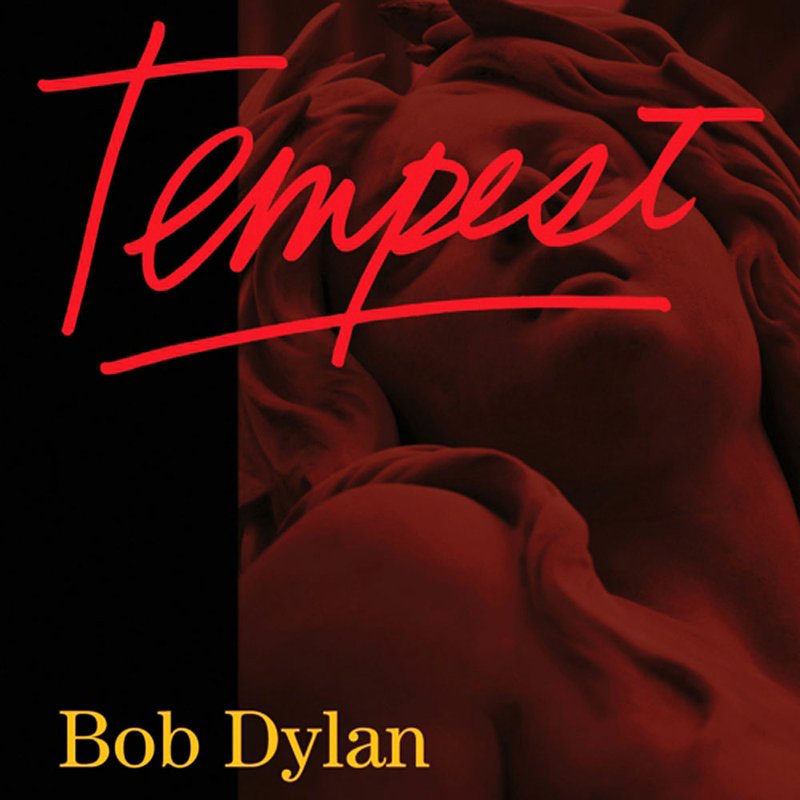

The only honest thing to do is to deal with the Dylan before us, the one with the past and all that, but who has a new record too. It’s one that goes along with his new voice, an ancient and ruined thing, a flapping of scar tissue down in the black hole of his trachea. Dylan sounds like merry death on Tempest (Columbia), his 35th studio album, his voice rusty and wheedling and occasionally taking on a breathy timbre that recalls — of all singers — Louis Armstrong.

This feels like a circle-closing album, though Dylan has debunked speculation that it’s a kind of farewell. Speculation arose when the title was announced — after all, The Tempest was probably William Shakespeare’s final play.

Tempest is not a completely successful album. There’s nothing here as completely satisfying as Dylan’s best work can be. There’s no “Like a Rolling Stone” or even “Not Dark Yet,” and, sentiment aside, “Roll On, John,” the albumclosing tribute to John Lennon, suffers from a tedious sophomoric lyric (though I’ll stand on Steve Earle’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say this: Dylan’s lyrics have never been the point. What matters is the way he delivers them).

But “Roll On, John” is the new album’s only clunker, an ordinary, almost generic tribute (“down in the quarry with the Quarrymen” — what? Someone’s kid could have written that) that probably isn’t as contrived as it feels. The rest of the album is consistently interesting, as Dylan examines the end days apocrypha of the — in Greil Marcus’ memorable phrase — “Old Weird America.”

Opening with the pre-rock swing of “Duquesne Whistle,” a train song co-written by Robert Hunter, the Grateful Dead house lyricist, that sets the stage as surely as Johnny Cash’s invitation to “ride this train.” But this is no simple joyride, as the conductor calls:

Listen to that Duquesne Whistle blowing Blowing through another no good town The lights of my native land are glowing I wonder if they’ll know me next time ’round

Next up is “Soon After Midnight,” which (for Dylan) passes for a fairly straightforward love ballad, with the feel of primeval rock ’n’ roll and doo-wop, allowing Dylan to slip on the satin jacket of the Bobby Vee he always wanted to be. The more you know his history, the more affected you’ll likely be.

That’s followed by the nimble jump “Narrow Way,” which sonically evokes Blonde on Blonde while groping for a benediction for a burned-out, blasted country “after the British burned the White House down.”

The middle stretch is highlighted by the stinging “Pay in Blood,” which feels informed by genuine anger, and “Early Roman Kings,” which feels like a 21st-century rewrite of “Masters of War” (aimed at 1-percenter privateers rather than the military industrial complex) married to a “Mannish Boy” stop-time blues.

Then there’s “Tin Angel,” a shaggy tale of lover’s retribution that recalls the superior songs “Isis” and “Lily, Rosemary & the Jack of Hearts.” Nice enough, but the real reason to hear the song is the locked-in banjo, snare and bass arrangement.

Which leads us to the title track, perhaps the most unexpected and delightful song Dylan has done in years, and one that defeats most expectations for a 14-minute, 50-verse retelling of a familiar story. When I heard of “Tempest,” my initial reaction was that it would be Dylan’s “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” without Gordon Lightfoot’s sonorous baritone. I thought it would be trite — that it would be messed up.

It’s not. It’s gorgeous in its way, a simple chord progression in the key of G, with Dylan — almost lightly — crooning over the top the swaggering metaphor of a nation going down. There’s some historical precision here, mixed with fancy — the verse about “Davey the brothelkeeper” is a remarkable little haiku — and cheekiness (“Leo took his sketchbook ...”). Some early reviews denigrated the track as sing-songy filler. It’s not that — it’s the best thing on a really good album.

That ought to be more than enough from our blue-eyed boy, Mr. Death.

E-mail:

Style, Pages 51 on 10/07/2012