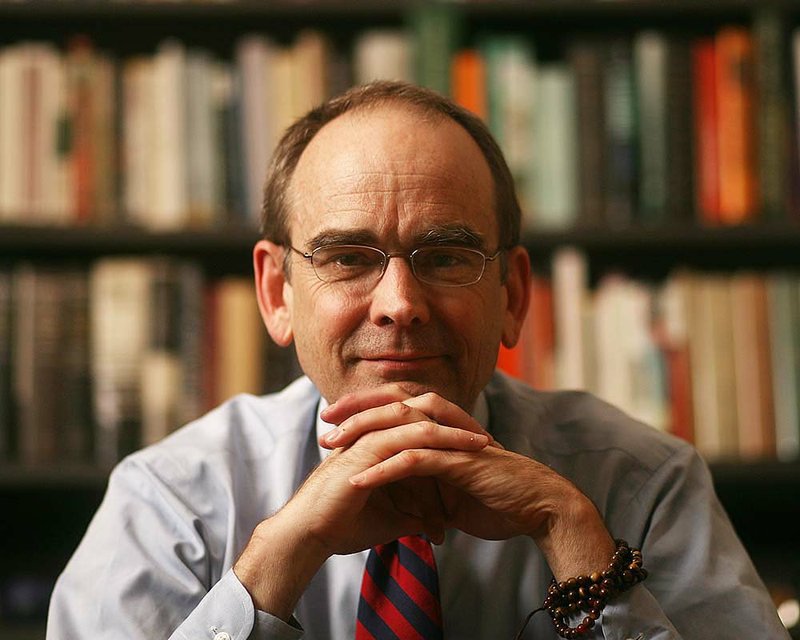

FAYETTEVILLE — Sidney Burris is the reason the Dalai Lama is coming to Arkansas on May 11 for two forums in Fayetteville about nonviolence.

Burris would never say this so plainly. As a practicing Buddhist, he strives to be modest. So on this matter, we’ll have to take other people’s word for it.

“If it had not been for Sidney, the Dalai Lama would not be here,” says Bill Schwab, the dean of Fulbright College. “[With] the TEXT Project, the interviews our students have done with the elderly who have lived in Tibet - I think he’s coming here out of appreciation for Sidney’s work and Sidney’s students’ work.”

The Tibetans in Exile Today (TEXT) Project was established in 2007 by Burris and Geshe Thupten Dorjee, an ordained Tibetan Buddhist monk. Dorjee shares an office with Burris, a professor of English at the University of Arkansas as well as the director of its J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences Honors Program.

The plight of Tibetans matters deeply to Burris, and he is afforded rare access because of his relationship with Dorjee.

Every other summer, the TEXT Project takes a group of UA undergraduate students to India, where they live in Tibetan refugee communities for three weeks. The purpose of the project is to document the stories of elderly Tibetans - people who remember the pre-1959 Tibet - before those memories are lost.

In India, the UA students record oral histories with elderly Tibetans. An estimated 100,000 Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama and fled their homeland in 1959 to escape the clutches of the People’s Republic of China. (The Dalai Lama left at the onset of the 1959 Tibet Rebellion because it was feared the Chinese would abduct or execute him.)

“Some of them have never told their stories to anybody,” Dorjee says. “These people are 70, 80 years old. These people have experiences in Tibet and India both. This last 10 years, these people have begun to disappear.”

During the TEXT Project’s most recent trip to India in 2009, the students were granted time with the Dalai Lama. They were able to tell him about what they were doing, and Burris says the Dalai Lama was impressed by the students’ enthusiasm for the project.

It was during that visit that Burris told the Dalai Lama he would be welcome to visit Arkansas any time. It was the third time Burris had invited the Dalai Lama to Arkansas; he made written offers in 2007 and 2008, both of which were turned down - albeit in different fashions.

“Within a month, they wrote back and said no [in 2007],” Burris says. “[In 2008] we highlighted what we had been doing. We didn’t get response for almost two months, and it was a different kind of no, a much more hopeful no [as in]: ‘We greatly value the kinds of things you’re doing to preserve Tibetan culture.’”

Upon returning to Arkansas in 2009, Burris prepared another letter of invitation for the Dalai Lama. That letter wasnever mailed, though, because on March 12, 2010, Burris received an e-mail from Tenzin Taklha, joint secretary to the Dalai Lama in India, informing him that the invitation had been accepted.

The Dalai Lama’s visit validates Burris’ work on behalf of Tibetans, and he hopes the excitement so far about the Dalai Lama’s arrival means people in Arkansas will become more interested in the Tibetan plight.

“We tilled the ground for a very long time,” Burris says modestly. “We didn’t do all this work to get the Dalai Lama here; we were doing this work because we believed in it.” LIKE BROTHERS

A search for Sanskrit brought Burris to the Dalai Lama.

Burris knew Greek and Latin and, as an aspiring classicist, wanted to learn the third language of the Indo-European language family. It was hard to find a good Sanskrit teacher in Vienna in the mid-1970s, when he was attending the University of Vienna, so he left Austria and headed back to America to study the language.

He enrolled in the University of Virginia and began taking courses in the ancient language. During one class in the fall of 1979, Burris’ Sanskrit professor said there was going to be someone visiting campus whom the students should all go see.

“He said, ‘Oh, by the way, since you all are studying Sanskrit, you might be interested in knowing [that] someone named the Dalai Lama will be visiting here,’” Burris recalls. “‘It’s his first time in this country, and you might want to go see him. He’s kind of a big deal.’”

Burris knew of the Dalai Lama, but he didn’t know much about him. So he went to hear the talk.

The Dalai Lama spoke of death and dying that day, and Burris was deeply moved. He began reading the Dalai Lama’s many writings, and from that point forward has rarely passed up an opportunity to see him in person.

Burris has seen the 14th Dalai Lama in India, Portugal and Canada, as well as around the United States.

“When he walks out on the stage [at Bud Walton Arena], they’re going to be able to see someone who in 500 years will be judged one of the greatest teachers - on the level of Socrates - and also, one of the most astute diplomats the world has ever seen,” Burris says.

If Burris knew little about the Dalai Lama before seeing him in 1979, he knew even less about the Tibetan people. Even in recent years, information has often been difficult to obtain.

He needed someone like Dorjee to gain access. Dorjee studied for 25 years at the Drepung Loseling Monastery in south India, and through him, Burris has been able to meet many exiled Tibetans living in India.

“Tibetan people, their culture is welcoming of anybody,” Dorjee says. “Tibetan people really don’t have a sense of strangers as Westerners think. Those people who [we] interview know why we’ve come.”

Burris’ relationship with Dorjee is evident in the two blogs he maintains. Mindspace is an instructional site for people who attend Dorjee’s meditation classes and provides follow-ups of that week’s teachings. The more widely read Tibetspace educates the general public on issues facing Tibetans in exile and those remaining in Tibet.

Burris and Dorjee met in Toronto in 2004, at the Kalachakra for World Peace being led by the Dalai Lama. Burris helped bring Dorjee to the UA on a full-time basis in 2006, and they began conceptualizing the TEXT Project almost immediately.

Burris and Dorjee have worked together on a number of projects. They founded the Tibetan Cultural Institute of Arkansas, which is dedicated to helping Tibetans preserve their cultural heritage, as well as to providing education opportunities concerning Tibetan culture, history and philosophy to Arkansas. They also teach a class together on the history and practice of nonviolence.

“They’re like brothers,”says Burris’ wife, Angie Maxwell, an assistant professor of political science at the UA as well as the Diane D. Blair Professor of Southern Studies. “They drive each other crazy sometimes, but they cannot do what they’re doing without the other.

“It’s a total cliche, but it’s like they’ve known each other for many lifetimes.” CRITICAL THINKING

With a laugh, Maxwell says it’s “Dalai Lama-palooza at our house right now.”

When this is all over, Burris will be freed to resume his life, which was pretty interesting even before Dorjee, the TEXT Project and the announcement of the Dalai Lama’s visit.

An only child, Burris was born and reared in Danville, a city on Virginia’s southern border. He grew up Episcopalian, and although he no longer identifies as one, he says he still has a great deal of respect for the tradition.

The specter of the Vietnam War loomed large when Burris was a teenager, as did the civil rights movement; in 1963, Danville was the scene of several violent incidents. Burris remembers many of his Sunday School classes as discussions of violence and nonviolence, a subject that holds great interest to him today.

“When I became a Buddhist [officially in 2004, although he had been calling himself an Anglo-Buddhist for years], my appreciation for the tradition from which I had come, the Anglican Episcopal tradition, skyrocketed,” Burris says. “I didn’t become a Buddhist out of violent disagreement with the spiritual tradition I had grown up with all my life. I still think it’s a wonderful tradition.”

Burris attended Duke University, graduating in 1975, and spent a year in Austria where he went to the University of Vienna, did a little tutoring and learned German. Upon returning to America, he did postgraduate work at Duke in German and Greek before enrolling at Virginia.

He thought he was going to be a classicist, but within a few weeks decided he had made a mistake. So he changed course and wound up getting his doctorate in English rather than classics.

“When you go from undergraduate to grad school, what happens is your pleasure becomes your profession,” he explains. “Sometimes you take great pleasure in things you don’t want to become your profession. That’s what happened to me.”

For more than 20 years, Burris was a prolific writer. He penned two books of original poetry, A Day at the Races and Doing Lucretius, and in 1990 published the book The Poetry of Resistance: Seamus Heaney and the Pastoral Tradition. (Burris’ work frequently dealt with Irish writers, and his dissertation was on Heaney.)

His essays and criticism appeared in numerous prominent publications, and he was given a “Notable Essay” distinction in three editions of the annual anthology Best American Essays.

It has gotten harder to find time to write recently. He has “been going 90 to nothing” since getting word the Dalai Lama was coming.

He describes the Dalai Lama as “like an approaching geologic event.” Burris heads the steering committee, along with UA director of special events Melissa Banks, and even though he goes to bed every night with his e-mail inbox cleared out, it refills by 9 the next morning.

Banks says the preparations for the Dalai Lama’s visit are more thorough than she can remember for any previous speaker - and that includes former U.S. presidents.

“It’s been a lot more intense,” Banks says. “For this event we’re having so many more people come than for other lectures we’ve had on campus. ... It’s pretty much nonstop.” MORE WORK TO DO

Even before March 12, 2010, Burris’ day jobs kept him rather busy.

Burris came to the UA in 1986 as an assistant professor of English, becoming an assistant professor with tenure in 1990 and a full professor in 2002. He took the Fulbright position on a temporary basis in 1995, and it became permanent in 1998.

Burris says his job changed dramatically in 2002, when the Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation donated a record $300 million to the UA. The result is that much of Burris’ position today is coordinating with students and faculty from the Fulbright College Honors Program.

His job involves administering money, which has to be done openly. At other times, a student will contact Burris, telling him that he has just learned of some amazing internship, but the application deadline is the next day.

So Burris will drop everything and help the student.

“Running any program involving faculty and students is like herding cats,” Schwab says. “This is not top-down. Sidney has very little power associated with his position as director of our honors program, so most of what he does is through persuasion, persuading faculty that thereis this particular need, or [assisting] a student who needs a mentor.

“When he was up for reappointment last year, his reviews were overwhelmingly positive.”

Burris isn’t entirely sure what he’s going to do when the Dalai Lama’s visit is over.

He talks of getting back to essay writing and is eager to get back on his bicycle. He raced competitively in his 40s, and although he doubts he’ll do that again, he looks forward to having more time to exercise.

A slim man who looks younger than his 58 years, Burris has always been athletic. He was a runner growing up and took up cycling after he injured his back.

“At the core of him, he’s three things - intellectual, spiritual and a loner,” his wife says. “His ideal day, he’d get up, meditate, ride his bike and then do some reading by himself. He’s really happy by himself; that’s why academics works for him and why Buddhism works for him.”

Truth be told, Burris hasn’t had a lot of time to contemplate the future. He expects there may be a bit of a letdown but notes with excitement that summer school begins less than two weeks after the Dalai Lama leaves.

Burris and Dorjee will spend three intense weeks readying 18 students, and then it’s back to India, to continue the work on the TEXT Project. So if there’s any letdown, it won’t last long.

There’s too much important work still undone.

“I asked him yesterday, ‘Are you so sick of this? Are you ready to be done?’” his wife says. “He said, ‘I would prepare for him for the rest of my life if I could.’ It’s been super rewarding for him to facilitate in something that’s so community involved.”

“I think he’ll go full force into India with a renewed commitment, because the Dalai Lama is aware of that project.”SELF PORTRAIT Sidney Burris

DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH March 9, 1953, Danville, Va.

MY DOG IS An Irish terrier, Bridey.

A SUBJECT I’D LIKE TO KNOW MORE ABOUT IS Contemporary physics, cosmology. I’d like to know more about the math involved with the origin of the universe, parallel universes.

IF I COULD ASK THE DALAI LAMA ONE QUESTION, IT WOULD BE Do you ever wear the gold Rolex watch that Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent you when you were a boy?

AFTER THE DALAI LAMA LEAVES, THE FIRST THING I’LL DO IS Turn around and hug my co-chair and my wife, Angie. Angie’s been propping me up since March.

ONE WORD TO SUM ME UP Persevering.

High Profile, Pages 39 on 05/01/2011