It was presidential campaign reporting unlike anything seen before. The reporter made it clear: He had no desire to join the permanent Washington press corps, or ever cover politics full time, and indeed he never did. He was contemptuous of Democratic centrists and unabashed about a sitting Republican president's depravity, and said so in prose that sounded like a punch-drunk H.L. Mencken spoiling for a bar fight. ("A treacherous, gutless old wardheeler who should be put in a ******* bottle and sent out with the Japanese current," he said of Democratic presidential aspirant Hubert Humphrey. And the incumbent in the White House? "A drooling red-eyed beast with the legs of a man and the head of giant hyena ... the dark, venal and incurably violent side of the American character that almost every country in the world has learned to fear and despise.")

This is the unmistakable prose of the late Hunter S. Thompson, who had high hopes that a one-off gig covering national politics 50 years ago — really a sop from his editor at a music magazine — might help him go from journalist to novelist. He already had two nonfiction bestsellers under his belt, one of which he'd reported out over years as an embed, covering an outfit at least as amoral as any in Washington: the Hell's Angels.

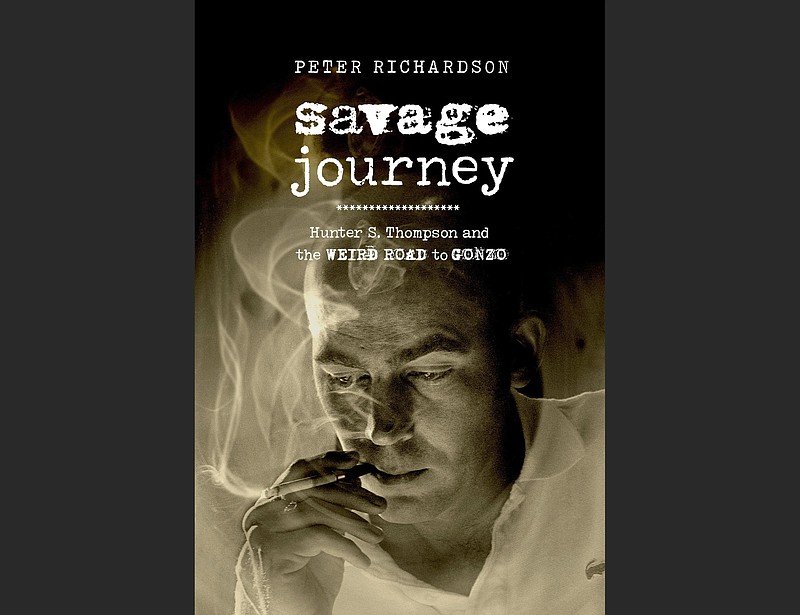

But if the Washington political establishment, including the press, thought the assignment was going to merit only a couple of magazine pieces, they had another think coming. Thompson influenced a new generation of political correspondents, says Peter Richardson, author of the newly published "Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo," a consideration of Thompson's literary influences and influence.

The campaign of 1972 was remarkable not only for investigative reporting but also for political and media coverage. That Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein are deservedly lionized and still wearing out shoe leather and breaking scoops 50 years later only reminds us of Watergate's watershed status. But those weren't the only journalistic foundations in 1972 that were shaken and stayed shook. Another duo also sparked journalistic revolutions that year.

JOURNALISM DUO

Thompson, whose Rolling Stone dispatches were recapitulated in "Fear and Loathing: On The Campaign Trail '72," liberated campaign journalism forever from deferential conventions and obligations to objectivity, and Thompson's ostensible assistant Timothy Crouse's Rolling Stone reporting on the campaign press corps, as collected in "The Boys on the Bus," was the ground zero for modern media reporting.

"Thompson sees the overall problem with politics; Crouse reports on and analyzes the press as part of the problem in depth," Richardson, also a lecturer at San Francisco State University, told me. "Thompson's supposed to have Crouse as an assistant but treats him like a teammate, going back to the room every night, going over what they learned during the day. Thompson feels disrespected by the Washington press corps, and tells Crouse, 'You know, maybe that should be the focus of your work: Watch those people, make them the story.' Out of this, they both produce reporting and two very different kinds of books that completely change journalism forever."

Thompson, he says, rightfully looms large for demolishing the idea that covering a campaign has to be objective day to day, or with the winner automatically cast as the hero a la Theodore White's "The Making of the President" books. Along with unabashed drug taking, hoaxing other reporters, and honing a cultivated but nonetheless genuinely menacing edge, Thompson quickly grasped the fact and advantage of being shunned by press corp heavyweights. "Thompson's determined to turn liabilities into assets: 'I'm not gonna do what everyone else is doing. I'm gonna write about what I see, present the unvarnished truth as I understand it,'" Richardson says. That truth still resonates, he explains, and is perhaps best summed up in this from Thompson's 1994 obituary of Richard Nixon in Rolling Stone:

"Some people will say that words like scum and rotten are wrong for Objective journalism — which is true, but they miss the point. It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place. ... You had to get Subjective to see Nixon clearly, and the shock of recognition was often painful."

GENERATION CHANGE

That Thompson's Rolling Stone dispatches were off-putting to older campaign reporters but resonant with younger ones, sometimes to the point of reverence, also signaled that generational change was beginning to affect assumptions and standards. Thompson was causing such ripples while inspiring as much awe for his drug and alcohol consumption, which made it an especially fun year to decide to report on the press corps, recalls Crouse, long out of journalism but still reveling in the memories.

"There were a lot of younger press guys in the mainstream press, who became our friends and we'd smoke dope with them, but Hunter. ... Hunter's genius, for me, was calibrating uppers and downers to keep getting exactly to the place he wanted to be, and I wasn't — that was just not something I was capable of doing," Crouse, 75, told me. "But he was such a mentor in such a natural way. If you were a writer — if you were serious about the craft — he considered you a brother."

"Thompson was one of the great satirists of American literature," Jeff Sartain, managing editor of the academic American Book Review and a modern literature scholar, told me by email. "In Thompson's writing, truth is often revealed through the tools of fiction, things like hyperbole, imagery and subjective perspective. His language, especially when he curses, has an almost poetic sense of sound and timing to go with his acerbic wit."

NO COLLABORATION

Crouse says that he and Thompson were delighted by the drip-drip-drip of The Washington Post's Watergate reporting but that there sadly was never a four-way sit-down between The Post and Rolling Stone partners. Strange as it is to consider, though, there may be some alternate reality out there in which Thompson might have shared The Post's pages with "Woodstein."

Thompson's archives are in the hands of a private consortium led by Thompson fan and friend Johnny Depp, so for his book, Richardson necessarily relied on historian Douglas Brinkley's authorized two-volume set of Thompson's letters. Among Richardson's exhumations: correspondence in 1963 between a 26-year-old Thompson and Washington Post and Newsweek publisher Philip Graham, in which Graham showed signs of mentoring Thompson into a job.

Perhaps even more mind-boggling: Thompson's initial note to Graham is a case study in calumny. "He's clearly angling for a job covering Latin America, and he does it not only by criticizing the Newsweek's coverage, calling it an 'abomination' and a 'fraud,' but Graham himself, and personally, calling him a 'phony' who's 'overpaid.'"

Yet Graham clearly found the approach if not charming, at least engaging enough to ask Thompson for a "somewhat less breathless letter, in which you tell me about yourself." And, he added, "don't make it more than two pages single space — which means a third draft and not a first draft."

Had Graham lived — he died by suicide on Aug. 3, 1963 — might Thompson have ended up toiling at The Post? Unlikely, says Richardson. "He lost every job he ever managed to land."