When the U.S. military recently sought to get rid of a stockpile of firefighting foam containing toxic “forever chemicals” known as PFAS, a facility near Arkadelphia accepted large quantities of the chemical waste and incinerated it, despite concerns from environmental advocates about the safety of the process.

As national concern grows about the pernicious toxic compounds, an environmental-law nonprofit has filed a lawsuit in federal court against the Department of Defense with the aim of halting the foam incineration happening in states, including Arkansas, absent more environmental review.

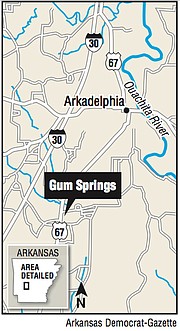

The sprawling hazardous-waste facility is on 1,300 acres near the railroad tracks just outside Arkadelphia and borders the tiny Clark County town of Gum Springs. Inside are kilns and afterburners designed to dispose of toxic materials, according to the facility’s corporate owner. The French environmental services conglomerate Veolia recently acquired the facility from the aluminum company Alcoa in a deal Veolia announced in early January.

[DOCUMENT: Read Veolia’s announcement of the deal with Alcoa » arkansasonline.com/45veolia]

The facility is linked to a problem facing the Defense Department: How should it dispose of excess firefighting foam containing the toxic chemicals while at the same time addressing contamination of soil and drinking water caused by past releases of the chemicals from military sites?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a vast group of manmade chemicals that do not occur in nature, do not break down in the environment and build up in the human body. For decades, the chemicals have been used in nonstick cookware, food packaging and carpets or clothes that repel water, stains and grease.

Because of the strength of the carbon-fluorine bond, they have become known as “forever chemicals.”

As a result of their persistence and mobility, the chemicals can find their way into soil and water, raising the risk to entire communities. Nearly all Americans are believed to have some level of PFAS in their blood.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Environmental Protection Agency and various studies have linked the chemicals to serious health problems in humans, including autoimmune diseases, thyroid disease, kidney and testicular cancer, endocrine disruption and cholesterol levels.

Two of the most widely studied and widespread chemicals in this category are perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

In January 2016, the Defense Department implemented a policy requiring all military installations to prevent PFAS releases during training exercises using the foam, according to a Pentagon official’s testimony to a Senate committee last year. The Pentagon also ordered installations to dispose of millions of gallons of excess foam containing PFOA, where practical.

But the Defense Department’s strategy of incinerating the foam to get rid of the military’s unused stockpile has proved to be controversial.

Veolia executive Bob Cappadona acknowledged in an interview with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that Arkadelphia has received PFAS-containing foam for incineration from contractors serving the Defense Department, but he could not give specific information about the volume of waste or a timeline, other than to say that firefighting foam has been incinerated at the plant within the past several months.

An incomplete Defense Department list obtained by the environmental-law nonprofit Earthjustice under the Freedom of Information Act and provided to the Democrat-Gazette indicates that the Arkadelphia facility has received more than 121,000 gallons of PFAS-related substances for incineration.

A facility in El Dorado has been authorized to receive the chemicals, based on Defense Department records, but an Earthjustice attorney could not say definitively whether the El Dorado facility has received PFAS. An executive with the El Dorado company said he could not find records indicating the receipt of foam for incineration.

THE LAWSUIT

Aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, was developed by the Navy in the 1960s in partnership with the chemical company 3M to put out fuel fires. The Department of Defense routinely used the foam during training exercises at military installations to douse jet fuel fires, leading to PFAS leaching into the soil and water of surrounding communities, despite research dating to the 1970s that suggested that the chemicals presented a health hazard.

In 2017, the Defense Department reported that releases of PFAS are known or suspected to have occurred at 401 active and former military installations.

In its report to Congress, the Defense Department listed three Arkansas sites with known or suspected PFAS releases: Eaker Air Force Base near Blytheville, which closed in 1992; Little Rock Air Force Base in Jacksonville; and Ebbing Air National Guard Base in Fort Smith.

[DOCUMENT: Read the Defense Department report » arkansasonline.com/45foam]

Soon after he was sworn in last summer, Defense Secretary Mark Esper created a task force to assess the PFAS issue in light of the military’s contamination of groundwater near bases nationwide.

Earthjustice’s lawsuit names the Defense Department and the Defense Logistics Agency, along with two companies — Heritage Environmental Services and Tradebe Treatment and Recycling — that were awarded contracts between 2018 and 2019 to transport and incinerate PFAS at qualified facilities like the one in Arkadelphia. The plaintiffs are the Sierra Club and three nonprofits in Ohio, Texas and Illinois.

Veolia and Alcoa are not named as defendants in the complaint.

The lawsuit, which was filed Feb. 20 in U.S. District Court in California’s Northern District, says the Defense Department violated the National Environmental Policy Act by moving ahead with a plan to incinerate the chemicals without conducting the required environmental review.

The complaint also claims that the Defense Department has ignored provisions on incinerating PFAS-containing firefighting foam in a recent defense spending law passed by Congress.

The National Defense Authorization Act passed by Congress this winter set defense spending priorities for fiscal 2020 and contained stipulations requiring the military to phase out PFAS-containing firefighting foam entirely by October 2024 (except onboard ships) and adequately incinerate excess foam in compliance with Clean Air Act regulations.

A spokesman for the Defense Department, Chuck Prichard, declined to answer questions from the Democrat-Gazette about foam incineration in Arkansas.

“As you are aware, [the Defense Department] has been named in legal actions regarding the topic of your query. Therefore, [the department] cannot comment due to the on-going litigation,” Prichard wrote in an email.

People living in the communities near incinerators are at risk because of the hazardous byproducts the Defense Department has not accounted for, Earthjustice attorney Jonathan Kalmuss-Katz told the Democrat-Gazette .

“We know there’s a risk, and we know that these chemicals are extremely persistent and extremely toxic, and yet nobody’s looked at the impacts on the surroundings,” he said. “That’s why we had to bring this lawsuit.”

The same trait that makes PFAS-containing foam useful for smothering jet-fuel blazes — the strength of the chemical bond in the long chain of carbon and fluorine atoms — means PFAS do not readily combust, Kalmuss-Katz said.

Because a facility has a hazardous-waste permit does not necessarily mean PFAS can be disposed of safely, he said.

“Just sending this stuff to incinerators and assuming, well, you know, it’s got a hazardous-waste permit so everything’s going to be fine — that doesn’t work for this type of material,” Kalmuss-Katz said. “[The Defense Department] has acknowledged that, and EPA has acknowledged that.”

So far, the Department of Defense has not given any assurance that any of the incinerators are capable of handling PFAS-containing substances, Kalmuss-Katz said.

‘BULLS-EYE’ ON ARKANSAS

Industrial production of PFOS and PFOA by eight major manufacturers was phased out in the United States under a 2006 Environmental Protection Agency agreement. Nevertheless, new variations of PFAS have entered the market.

At the moment, the EPA does not regulate PFAS as a hazardous material or contaminant. The agency’s only standard on the chemicals is a nonenforceable health advisory that says two of the compounds, PFOA and PFOS, should not exceed 70 parts per trillion in drinking water.

But recently, the agency has tiptoed closer to regulating PFAS under the Safe Drinking Water Act. In February, the agency opened a public-comment period in a proposed step to establish a national drinking water regulation for PFOA and PFOS.

Emitting PFAS or other hazardous incineration byproducts into the air is worrying, according to Jane Williams, chairwoman of the Sierra Club’s National Clean Air Team. After exiting a waste facility, the chemicals may be deposited on the ground and subsequently end up in water, adding to PFAS contamination in the environment.

“Emitting any of it into the air is highly problematic from a public-health perspective, and we’re already overexposed to these chemicals,” Williams said.

She said it’s unfortunate to have two incinerators in the same state authorized to receive PFAS waste from the military.

“The bulls-eye is kind of on the state of Arkansas,” Williams said.

A spreadsheet obtained by Earthjustice from the Department of Defense under the Freedom of Information Act indicates that a large quantity of PFAS-related waste was sent to Arkadelphia for disposal. According to the document, at least 121,082 gallons of waste in the form of liquid concentrate and PFAS-contaminated water was sentto the Arkadelphia facility, as well as a much smaller amount of waste in gallons and drums of unknown sizes.

Ownership of the Arkadelphia plant changed hands recently. In January, Veolia, the French multinational, announced that it had agreed to buy the plant in a $250 million deal from Alcoa.

When asked if there is the possibility that PFAS have exited the facility through the air or have been deposited into the water, Cappadona, the president and chief operating officer of Veolia’s environmental solutions and services group, referred to the facility’s environmental controls.

“I certainly won’t speak in terms of absolutes, but I will say that we are operating the facility in full compliance with all of the hazardous waste management regulations for the operations of the incinerator,” Cappadona said.

Air pollution controls are “unique and very robust to ensure that we are controlling the emissions from the facility,” Cappadona said.

He characterized PFAS contamination as “an emerging environmental challenge.”

A year or two ago, “you wouldn’t hear people speaking about PFAS as being a primary environmental challenge as it is being spoken about today,” Cappadona said. “So we continue to track and participate in the development of regulations as well as environmental research on the treatment of PFAS.”

Afterburners enable the incinerator to reach extremely high temperatures — enough to destroy any organic materials — Cappadona said.

However, because the facility is working with a contractor, not directly with the Defense Department, the plant has received no specific guidance from the military on what temperature an incinerator should reach to destroy the chemicals, Cappadona said.

“The operating parameters of the incinerator are set by the regulatory community,” he said.

While Cappadona could not confirm how much foam has been incinerated at the Arkadelphia plant, he did not dispute the figure obtained by Earthjustice. He declined to name the contractor working with the military to send firefighting foam for incineration.

He declined to say how much the company has been paid to handle the waste from the military, nor would he confirm how much more firefighting foam the facility might incinerate in the future.

Within the environmental services industry, Cappadona said, there is an understanding that large volumes of PFAS, like the stockpile of firefighting foam, should be removed to prevent them from becoming a bigger environmental problem.

“If the research community or the regulatory community has advancements that would take protection to another level, Veolia will certainly be the first one to do that,” Cappadona said.

CITY MANAGER: ‘NOT CONCERNED’

When asked about the PFAS incineration, Arkadelphia City Manager Gary Brinkley said the city is aware Veolia is permitted to incinerate the foam.

“We are not concerned as the incineration of the PFAS through the kiln and afterburners breaks the product down to simple carbon and nitrogen compounds,” Brinkley wrote in an email. “Although PFAS is not currently regulated, Veolia handles the materials as if it were. Veolia [sits] on the Dept. of Defense panel which is studying the disposition of PFAS to make sure they remain on the forefront of addressing this chemical.”

But the idea that chemicals breaks down easily into simple, harmless atoms isn’t strictly true, according to Williams, the Sierra Club advocate. If you break the bonds of the compound at all through incineration, the fluorine atoms bond to hydrogen and form hydrogen fluoride, a highly corrosive toxic compound, she explained in response to Brinkley’s statement.

“This is just someone who just fundamentally doesn’t understand what happens in an incinerator when you burn fluorinated chemicals,” Williams said.

The Defense Department appears to be aware of the risks of trying to incinerate PFAS, including the chance that incineration may emit hydrogen fluoride or other noxious byproducts. The Earthjustice complaintrefers to a 2017 solicitation from the Air Force requesting proposals for “novel” disposal technologies for the firefighting foam.

“A practical method for disposal of AFFF [aqueous film-forming foam] residues and AFFF concentrate will have to manage several significant challenges,” the solicitation said, and mentioned the “many likely byproducts” of PFAS incineration such as hydrogen fluoride or fluoroacetates, a poisonous compound used as rodenticide.

When asked about Williams’ assessment, the city manager said he had no further comment.

“I am not a chemist or member of any special interest group,” he wrote in an email. Before he crafted his earlier reply to the Democrat-Gazette , Brinkley said he consulted with a contact at Veolia to verify “what I had heard said before when they were seeking their permit under the Alcoa flag last year.”

It is unclear whether the other facility in Arkansas that appears on the Defense Department list of authorized recipients of PFAS-related waste, in El Dorado, has received any for incineration.

Phillip Retallick, senior vice president for compliance and regulatory affairs at Clean Harbors Environmental Services, was unable to say whether the El Dorado plant has received any of the firefighting foam. He emphasized that PFAS is not regulated as a hazardous material.

“We would need more information, specifically, directly from the U.S. [Defense Department] that these shipments actually came to our facility,” he said. “That’s all I can say. We don’t have any record of them being received at our El Dorado facility.”

He allowed that “it’s conceivable” the material may have gone through the El Dorado facility for a short period of time and then was transferred to a third party, such as a landfill, for disposal.

“Since it’s not regulated, it can be disposed of either at an incinerator or a landfill, but I don’t even have it in my system,” Retallick said.

Brown Hardman, a member of the Clark County Quorum Court and former vice mayor of Arkadelphia’s city board of directors, suggested that the average Arkadelphia resident, like him, is unaware of the PFAS incineration happening nearby.

He said residents should be concerned about the Veolia facility.

“Not because I think they’re doing anything wrong, but because we don’t know what they’re doing,” Hard-man said.

He said he wants to see greater transparency of activities at the Arkadelphia plant in light of Veolia’s new ownership.

“I think this is as critical as anything, and it’s flying under the radar,” Hardman said.