LONDON -- Julian Assange had just pulled off one of the biggest scoops in journalistic history, splaying the innards of American diplomacy across the Web. But technology firms were cutting ties to his WikiLeaks website, and a Swedish sex-crime case was threatening to put him behind bars.

Caught in a vise, the silver-haired Australian wrote to the Russian Consulate in London.

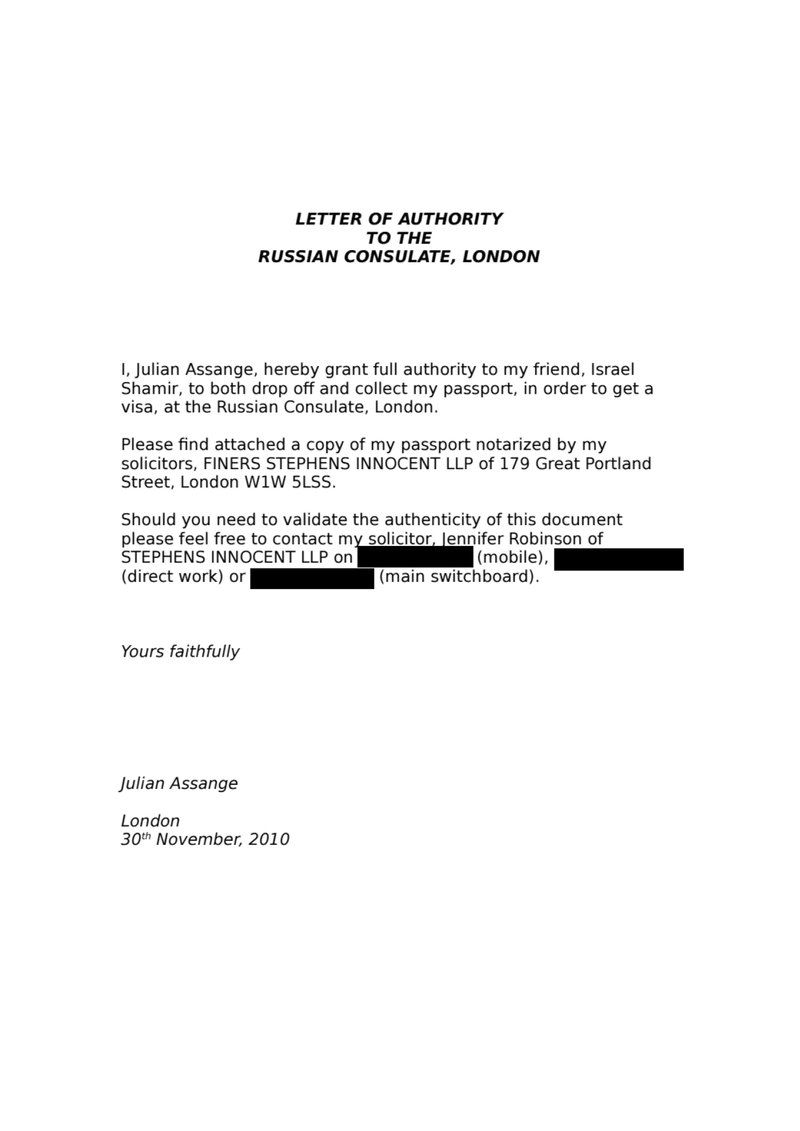

"I, Julian Assange, hereby grant full authority to my friend, Israel Shamir, to both drop off and collect my passport, in order to get a visa," said the letter, which was obtained exclusively by The Associated Press.

The Nov. 30, 2010, missive is part of a much larger trove of WikiLeaks emails, chat logs, financial records, secretly recorded footage and other documents leaked to the AP. The files provide both an intimate look at the organization and an early hint of Assange's budding relationship with Moscow.

The ex-hacker's links to the Kremlin would become increasingly salient before the 2016 U.S. presidential election, when the FBI says Russia's military intelligence agency directly supplied WikiLeaks with stolen emails from Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman and other Democratic figures.

In a statement posted to Twitter, WikiLeaks said Assange never applied for the visa or wrote the letter, naming a former associate of his as the alleged source of the document. WikiLeaks did not return a follow-up email seeking clarification on whether Shamir applied on his behalf, or whether a lawyer or someone else at WikiLeaks might have drafted the letter. The Russian Embassy in London said it doesn't discuss the personal details of visa applicants.

The AP has confirmed the authenticity of many of the documents by running them by five former WikiLeaks associates or by verifying nonpublic details such as bank accounts, telephone numbers or airline tickets.

One of the former associates, an ex-employee, identified two of the names that frequently appeared in the documents' metadata, "Jessica Longley" and "Jim Evans Mowing," as pseudonyms assigned to two WikiLeaks laptops.

Among other things, the documents lay out Assange's campaign to avoid being arrested and extradited to Sweden over allegations that he sexually molested one woman and raped another during a trip to the Scandinavian country in August 2010.

Assange has always denied wrongdoing in the case, which he cast as a prelude to extradition to the United States. The Swedish prosecution jeopardized what at the time was WikiLeaks' biggest-ever disclosure: the publication of around 250,000 U.S. State Department cables. Swedish authorities issued a warrant for his arrest on Nov. 18, just 10 days before the cables were published, with bombshell revelations about drone strikes in Yemen, American spying at the U.N. and corruption across the Arab world.

Metadata suggests that it was on Nov. 29, the day after the release of the first batch of State Department files, that the letter to the Russian Consulate was drafted on the Jessica Longley computer.

The AP couldn't confirm whether or when the message was actually delivered, but the choice of Israel Shamir as a go-between was significant. Assange's involvement with Shamir, a fringe intellectual who once said it was the duty of every Christian and Muslim to deny the Holocaust, would draw indignation when it became public.

Shamir told the AP he was plagued by memory problems and couldn't remember delivering Assange's letter or say whether he eventually got the visa on Assange's behalf.

Shamir's memory appeared sharper during a January 20, 2011, interview with Russian News Service radio . Shamir said he'd personally brokered a Russian visa for Assange, but that it had come too late to rescue him from the sex crimes investigation.

Russia "would be one of those places where he and his organization would be comfortable operating," Shamir explained. Asked if Assange had friends in the Kremlin, Shamir smiled and said: "Let's hope that's the case."

On Nov. 30, 2010 -- the date on the letter -- Interpol issued a Red Notice seeking Assange's arrest, making any relocation to Russia virtually impossible. With legal bills mounting, Assange turned himself in on Dec. 7 and his staff's focus turned to getting him out of jail.

As they gathered money, Assange's allies also plotted what to do once the WikiLeaks founder was released.

One document showed Guatemalan human-rights lawyer Renata Avila floating the idea of jumping bail.

"I will advise him to seek asylum abroad: we already contacted the Ministry of Justice in Brazil, there is a possibility to run out of the country in a Brazilian ship," Avila told fellow WikiLeaks supporters in a memo.

Assange would eventually skip bail, darting into the Ecuadorean Embassy on June 19, 2012. It sparked a standoff that continues to this day.

Information for this article was contributed by Varya Kudryavtseva and Mauricio Savarese of The Associated Press.

A Section on 09/18/2018