WASHINGTON -- When Japanese torpedoes sank the USS Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, it became the temporary tomb for hundreds of Americans.

Now, nearly 77 years later, an agency of the U.S. Department of Defense is working to identify their exhumed remains, using DNA from relatives. It's a painstaking task taking place around the world.

The Defense Department has promised to give "the fullest possible accounting" for all American servicemen who died in World War II.

So far, researchers with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency have identified the remains of nearly 200 servicemen who died in the surprise attack on the Oklahoma, including at least four Arkansans.

This month, the agency has disclosed eight more crew members, including Water Tender 2nd Class Clarence M. Lockwood, a native of Smithton in Clark County. He was 21 at the time of his death.

Last month, the list of those identified included Navy Seaman 1st Class Richard L. Watson of Crossett.

The remains of another sailor from Arkansas, Navy Seaman 1st Class Henry G. Tipton of Imboden, were identified in February.

And in April, Fireman 2nd Class John D. Wheeler of Gaither was laid to rest at Gaither Cemetery, 10 miles southwest of Harrison. Wheeler's remains had been identified in August 2017.

Five other shipmates from Arkansas remain unaccounted for, according to the agency's website: James Cecil Webb, Dan Edward Reagan, Earl Maurice Ellis, Isaac Parker and Samuel Cyrus Steiner.

Most died on board the vessel, which capsized in minutes. Many were entombed there until late 1943, when the ship was righted and raised. Of the 429 crew members who perished in the attack, only 35 were positively identified by decade's end.

In 2015, coffins containing the remains of as many as 388 of the unidentified sailors and Marines were exhumed.

Using dental records, DNA and other methods, experts have been working since to separate, identify and return the remains to the families of those who died.

In December, the agency announced that it had identified the remains of 100 from the ship.

Similar work is underway around the world.

This month, the agency accounted for the remains of three World War II-era U.S. troops who died in Germany, one in Bulgaria, one on Saipan and another in Tarawa, an atoll in the Pacific. A soldier, exhumed from a South Korean cemetery, also was identified.

U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton, a Republican from Dardanelle who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, says the military goes to great lengths to identify the fallen and bring them home.

"The commitment that the agency shows to its mission tells every soldier, sailor, airman and Marine today that whatever may happen to them on the field of battle or in humanitarian relief or training exercises, the country will spare no expense to bring them home and it will never forget the sacrifice that they made," Cotton said.

The task of identification is enormous.

Of the 405,399 U.S. servicemen who died in World War II, more than 72,000 are unaccounted for, including 849 from Arkansas, according to agency data.

Only a fraction -- perhaps 26,000 -- are considered "possibly-recoverable" by the agency.

The government also is trying to account for 7,683 servicemen in Korea; 1,594 from the Vietnam War; five in the Persian Gulf wars; 126 from the Cold War; and one who was shot down during a 1986 attack on Libya.

Until the 1950s, fallen soldiers were not swiftly returned to the United States.

"It's called the policy of concurrent return and that only started in the Korean War," Cotton said. "We're accustomed to it today because remains, especially at the height of the Iraq War, were arriving at Dover [Air Force Base] within 24 to 48 hours, but only in Korea did that become the custom."

During World War I, the 117,000 "Americans killed in Europe were interred in various cemeteries in Europe with the intent that they remain there for eternity," Cotton said.

"Under very intense advocacy from war widows and war mothers, Congress ... provided the funds for the military to bring back the remains of anyone who so wished. And a pretty large majority of families had the remains brought back but that was only after the war."

After World War II ended, fallen U.S. troops were again returned home.

But some could not be identified.

Accounting for remains from the USS Oklahoma is especially challenging. Many of the bodies remained in fuel-fouled waters for nearly two years.

Entries in a salvage diary, preserved by the National Archives, provided a grisly tally that grew day by day in the fall of 1943: "18 skulls, 1 partial body, and miscellaneous bones [recovered] on 18 October, making a total of 251 skulls and bodies recovered thus far."

Some of the bones weren't recovered until mid-1944.

Initially, they were buried at two cemeteries. After the war, they were disinterred and studied. Most could not be identified.

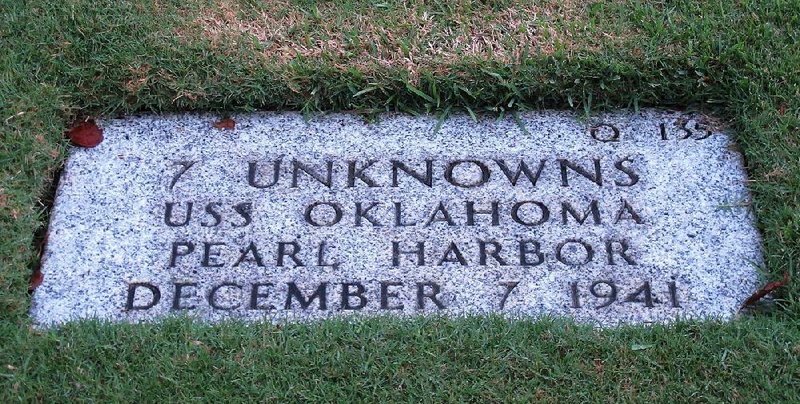

The remains were eventually placed in 61 caskets and moved to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which opened in Honolulu in 1949. For decades, they were classified as "unknowns."

Today, after decades of technological advances, it's now possible to give families a fuller accounting.

In 2015, the Defense Department decided to disinter and attempt to identify the remains.

They were shipped to Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska.

"We sent them to our laboratory where they did an inventory of all the remains," said Sgt. 1st Class Kristen Duus. "They had more than 10,000 pieces that they had to sort through."

Family members of the missing were asked to provide DNA samples.

"It's just a cheek swab and we put that into our system," Duus said.

When the DNA from the relatives matches the genetic material found in the bones, the agency notifies the next of kin.

"They're given all the details from start to finish about the circumstances of their service member's loss and the identification," Duus said. "The family gets to choose when and where they want to have the funeral for their servicemen and each service member is provided with a funeral with full military honors."

Some opt to have the burial in Honolulu. Others select Arlington National Cemetery, across from the nation's capital. In many instances, the final rites are in the sailor's home state.

The agency hasn't announced where Lockwood will be laid to rest and wouldn't release information about his next of kin, saying it wasn't authorized to do so.

Ken Tipton, whose half brother Henry Tipton, also died on the Oklahoma, said it's hard for families to handle the loss of a loved one, especially when their remains have never been identified.

Their father, William Kaster Tipton, "went through a lot of trauma, he had a lot of grief,'" the surviving son said.

"The fear was there that he could've been killed. But was he killed instantly? Did he drown? Did he suffocate? How did it happen? Did he suffer?" Tipton said. "All those things were unknowns. ... He went to his grave in 1985 never knowing."

A positive identification, a funeral, a burial might have given his grieving father some closure, he said.

The sailor's sister, Willene Tipton McGuire, gave a DNA sample in March 2013, two months before she died, Tipton said.

Early this year, a match was made. "We were notified in February. Then I had a meeting in April with the Navy and they showed me the pictures of the bones. ... There was a skull, two arm bones, I think three leg bones and hip bones. Enough that they felt like it was a positive identification," he said.

If the Tiptons waited a few more years, additional bones might be identified, they were told.

They opted to proceed with the burial.

Once a match was made, family members from across the country gathered at Opposition Cemetery near Ravenden to pay their final respects.

The World War II veteran was laid to rest beside his mother, who had died in childbirth long before the war. It's a site his grief-stricken father had selected.

Cousins, now in their 90s, who knew and remembered the sailor, attended his funeral.

Flags flew. Soldiers saluted. Hundreds turned out.

"It was an outpouring of patriotism and love for country," Tipton said.

SundayMonday on 09/16/2018