Ray Benson of the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture is pointing out the various varieties of cotton as we drive alongside the runway of the Manila Airport in Mississippi County.

A Manila native who has been employed by the university for two decades, Benson was destined to work with cotton. His great-grandfather was the first member of his family to farm in this area.

An experienced agronomist, he has watched the evolution of the cotton industry his entire life. He helps oversee almost 30 acres of test plots at the airport. Those plots technically are part of the UA's Northeast Research & Extension Center at nearby Keiser, where 780 acres of land are controlled by the university.

Cotton is no longer king in Arkansas, but the area around Manila remains cotton country. I make the short drive from Manila to Keiser the next day. Then on to Wilson to follow U.S. 61 north through Osceola and Blytheville before returning to Manila. All along the route, fields are white with cotton as the 2018 harvest begins.

"There was a time when Mississippi County grew more cotton than any county in the country," says Benson, who received his bachelor's and master's degrees in agronomy and crop science from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. "I would estimate there are still 110,000 acres of cotton being raised in the county."

There were about 485,000 acres of cotton planted across the state this year, up from 445,000 acres last year. It's the third consecutive year of increased cotton acreage. Polyester, a cotton competitor, is in decline. At planting time, it was

reported that Chinese farmers were having problems with their crops, which made cotton a good bet for Arkansas producers.

"We're seeing cotton in places we hadn't seen it grown in 15 to 20 years," UA extension cotton agronomist Bill Robertson said earlier this year. "Their daddies and granddaddies grew cotton, but they hadn't. The profit potential for cotton is starting to look better."

Those 485,000 acres still pale in comparison with the 3.6 million acres of soybeans and the 1.4 million acres of rice grown in Arkansas this year. A rainy September threatened cotton yields as the harvest began.

"We sit at the house and get sick every time we hear it pounding on the roof," Benson says. "One rain, one event, one time may be no big deal."

There were, however, multiple storm systems, leading Benson to say: "We need it to quit raining, dry out and get sunny pretty soon."

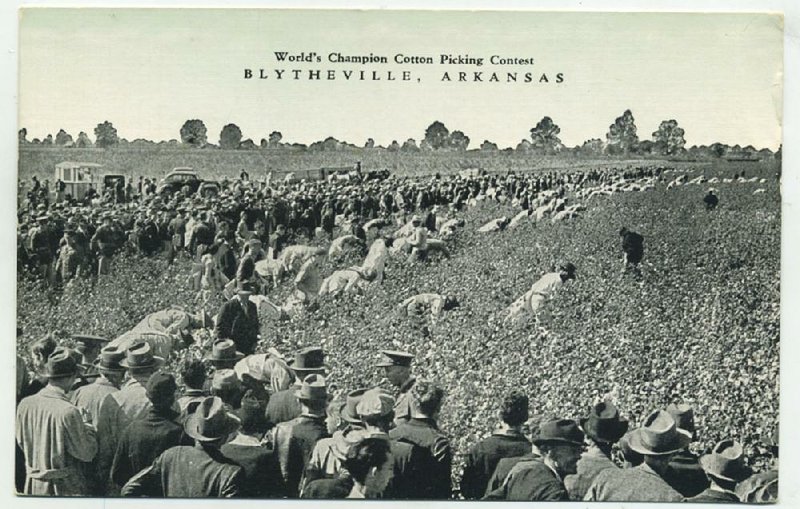

Arkansas' cotton harvest begins in the middle of September and sometimes runs until early November. What's now picked by huge mechanical cotton pickers once was the job of tens of thousands of sharecroppers and tenant farmers. In many ways, the history of cotton cultivation is the history of Arkansas.

In his book Empire of Cotton: A Global History, Sven Beckert notes that "the entry of the United States into the empire of cotton was so forceful that cotton cultivation in the American South quickly began to reshape the global cotton markets."

Consider these facts:

-- In 1790, three years before Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, the United States produced 1.5 million pounds of cotton.

-- By 1800, the United States produced 36.5 million pounds. That number was up to 167.5 million pounds by 1820.

-- By 1802, the United States had become the most important supplier of cotton to the British market.

-- By 1857, the United States was producing almost as much cotton as China.

"American upland cotton, which Whitney's gin worked up so efficiently, was exceedingly well suited to the requirements of British manufacturers," Beckert writes. "When the gin damaged the fiber, the cotton remained suitable for the production of cheaper, coarser yarns and fabrics in demand among the lower classes in Europe and elsewhere. But for American supplies, the miracles of mass production of yarn and cloth, and the ability of new consumers to buy these cheap goods, would have foundered on old realities of the traditional cotton market. The much-vaunted consumer revolution in textiles stemmed from a dramatic transformation in the structure of plantation slavery."

The blackland prairies of southwest Arkansas were the center of cotton production in the state before the Civil War, making Washington in Hempstead County a key place for trade. It wasn't until well after the Civil War that most of the swamps were drained and the hardwood timber was cut from the vast bottomland hardwood forests of east Arkansas. Once that occurred, the Arkansas Delta became an integral part of the South's cotton empire. In the early 1900s, the Wilson Plantation in Mississippi County was one of the largest cotton plantations in the world.

Beckert explains that the westward expansion of the cotton empire "occurred in two distinct ways. Cotton production expanded into the remote hinterlands of older American cotton states such as Georgia and the Carolinas, now made accessible by railroads, where white upcountry farmers began growing much larger quantities. In the South Atlantic states, annual production, for example, increased by a factor of 3.1 between 1860 and 1920. In Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi, by contrast, annual cotton production stayed level until the end of the century and declined by about 25 percent by 1920 due to the exhaustion of cotton soils and the emergence of more productive cotton-growing areas farther west.

"Yet even despite the tired soil, cotton production dramatically expanded in some areas, such as in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta, where large numbers of African Americans cultivated cotton, enabled by new railroads, canals and levees. As a result, by 1900, one of the most highly specialized cotton-producing areas in the world emerged. The most dramatic expansion of cotton agriculture, however, occurred farther to the west."

Production in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas went from 1,576,594 bales in 1860 to 7,283,000 bales by 1920.

As the 20th century dawned, the size of Arkansas Delta plantations was becoming larger. Plantation owners employed hundreds and sometimes thousands of tenant farmers and sharecroppers.

"A typical Arkansas cotton tenant, black or white, rented 40 acres from a landowner and farmed with his own mules, harrow, planter and family for labor," Van Hawkins writes for the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. "Landowners got about one-fourth of the crop with the remainder going to the tenant. At the lower end of the tenant food chain, a sharecropper lacked equipment and capital so he farmed with landlord-supplied equipment and capital. Typically, his family received only 50 percent of the crop and had to buy supplies and personal items from plantation commissaries, sometimes at high markups.

"Sharecroppers, particularly African Americans who lacked mobility due to race, did little more than survive. They generally had little cash after settling up with landlords and often found themselves deeper in debt to the company store."

Major cotton-related events in Arkansas history included the Lee County cotton picker strike of 1891, the Elaine Massacre of 1919 and the formation of the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union in 1934 as tension between landowners and tenant farmers grew.

"Profitable cotton prices, sometimes as high as 30 cents a pound, crashed along with the stock market at the beginning of the Great Depression," Hawkins writes. "There was a drought of financing as banks closed and five-cent cotton devastated state producers. In 1933, the U.S. government devised a program to pay farmers for plowing up cotton acreage to reduce supply and, theoretically, create higher prices. The program made plow-up payments directly to landowners and directed them to share the money with tenants. Some owners chose to evict tenants rather than share payments, which set in motion numerous conflicts between planters and tenants."

Along with the growth of cotton acreage in Arkansas came social and demographic changes. The burden of segregation and the loss of work due to the mechanization of cotton farming ensured that Arkansas would be a leading participant in what's known as the Great Migration of blacks from the rural South. A severe drought in 1930-31 and low cotton prices also drove white sharecroppers out of the state. It was a trend that would continue for several decades. Arkansas lost a larger percentage of its population from 1940-60 than any other state. Nationally, about 6 million blacks fled the South from 1915-70.

In her Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration, Isabel Wilkerson writes: "The Great Migration ran along three main tributaries and emptied into reservoirs all over the North and West. One stream carried people from the coastal states of Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia up the Eastern seaboard to Washington, Philadelphia, New York, Boston and their satellites. A second current traced from the central spine of the continent, paralleling the Father of Waters, from Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee and Arkansas to the industrial cities of Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh. A third and later stream carried people from Louisiana and Texas to the entire West Coast, with some black Southerners traveling farther than many modern-day immigrants."

Wilkerson notes that by the mid-1930s, some grade-school classrooms for blacks in Milwaukee had almost every student from Arkansas, Mississippi or Tennessee. The out-migration continues to this day in most Arkansas Delta counties, some of which now have less than half the population they had in 1950. Monroe County lost a larger percentage of its residents--more than 20 percent--between the 2000 census and the 2010 census than any other Arkansas county.

The irony is that the land in these Delta counties is more valuable than ever, producing bumper crops most years of soybeans, rice, cotton, corn, wheat and grain sorghum. Arkansas farmers are among the best in the world at what they do. They're so efficient, in fact, that they need few employees. Land that once required hundreds of sharecroppers and tenant farmers to chop and pick cotton can now be farmed with just a handful of laborers.

Cotton still generated about a third of Arkansas' agricultural income in the early 1960s. By the 1980s, it was down to about 20 percent. In 2015, cotton acreage was the lowest on record in Arkansas with 205,000 acres planted. That number was up to 360,000 acres in 2016.

The uptick continued in 2017 and this year. Arkansas usually ranks in the top six states nationally when it comes to cotton production. Cotton has lived on as an important crop in Arkansas, but it never will have the influence it once had in shaping the state's economy and history.

Editorial on 10/14/2018