Arkansas Baptist College misspent hundreds of thousands of dollars in federal money and "is in a serious financial crisis," according to an internal report obtained by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

The private, historically black Little Rock college compounded its cash-flow problems by leaving money on the table year after year, says the scathing "operational assessment" by the Wesley Peachtree Group, a Georgia accounting firm that specializes in higher education and historically black colleges.

Dated June 30, 2017, and marked "strictly confidential," the 60-page document adds more context about Arkansas Baptist's long-standing financial struggles -- including problems with the type of money at the heart of an ongoing crisis that has left faculty and staff members without paychecks.

Howard Gibson, the college's interim president, said Tuesday that the U.S. Treasury Department had "delayed" payment of federal money because of issues with U.S. Department of Education Title III and Title IV funds that predated his administration. As a result, the college missed its April payroll.

College leaders said they were looking for other funding sources to pay employees -- such as a short-term loan or line of credit. Gibson has since declined to answer specific questions, other than saying he had no update to provide.

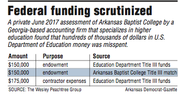

The Peachtree review of the college's finances found that $475,000 in Title III money -- federal grants meant to establish or improve academics, facilities and endowments -- had been improperly spent. It also says the college possibly owed the Education Department more than $500,000 it spent in Title IV money, which is student financial aid.

Ex-president Joseph Jones brought in Peachtree during his 15-month tenure and later left the college under disputed circumstances. Hired in September 2016 to replace longtime president Fitz Hill, Jones said in an interview that problems with federal money cited in the report date to fiscal 2014.

At the time of Jones' exit, the college in a news release said he was fired for cause because he wasn't transparent about financial problems and because of a decline in enrollment.

Jones said he informed the board of trustees he was resigning for "good reason" -- which would have triggered severance payouts -- because the board obstructed him from performing his job and because of what he called "gross financial conditions I ended up discovering."

The board was aware that Jones brought in Peachtree to conduct the assessment, and he presented trustees with the final report, Jones said.

A Peachtree official confirmed that the firm completed the assessment but declined to comment.

An Education Department spokesman said the department had not seen the document and declined to answer emailed questions. The Treasury Department's press office has not responded to multiple inquiries.

Repeated attempts to schedule separate interviews with Hill and board Chairman Kenneth Harris were unsuccessful.

It's not clear whether the cases of misspent money highlighted in the report are the same ones Gibson referred to in explaining why the flow of federal money to Arkansas Baptist stopped. The school's audit for fiscal 2017 -- and earlier years -- found several problems with how school officials handled federal money and maintained documentation.

The Peachtree report uses blunt language in its appraisal of the school. Alleged misspending of federal money was just a portion of the broader review, which called for immediate changes and proposed a plan to achieve financial stability at the perennially cash-strapped school.

"An analysis of ABC's financial condition reveals insolvency and that current plans underway for resolution are insufficient," the report says. "There is an URGENT need to stop the fiscal bleeding and return the College to solvency. ABC is in a serious financial crisis."

The report cited a "lack of competencies" and "complete disarray" in the financial-aid office for a failure to maximize federal reimbursements. It also says the college forfeited $10.8 million in student tuition and fees because of "dismal" collection efforts.

Because it is continuously delinquent on bills, the college's "fiscal fortunes" were "reduced to the mercy of its creditors," the report says.

LONG-STANDING WOES

The 134-year-old Arkansas Baptist, on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, is among the state's oldest postsecondary schools. The only Baptist-affiliated, historically black college west of the Mississippi River, it has open admissions standards in which most applicants who have a high school diploma or equivalent are accepted.

The college's graduation rate is 18 percent, according to its U.S. Department of Education scorecard. Roughly 9 out of 10 students at the college rely on loans, and about 8 in 10 who've taken the loans have not paid a single dollar toward the principal, according to the department.

In recent years, news reports have documented Arkansas Baptist's financial problems and a high-stakes run-in with its accrediting agency, the Higher Learning Commission.

The commission in 2015 ordered the college to show why its accreditation should not be stripped because of its financial insecurity. Although the school maintained its accreditation as part of a November 2016 decision, Arkansas Baptist is undergoing a follow-up review to see if it is making promised improvements.

Some of the college's financial troubles have been traced to 2013, when the Education Department placed the college on "Heightened Cash Monitoring 2" status after "severe findings" were noted during an annual audit. In other cases, plunging enrollment has been blamed.

The cash-monitoring designation -- applied to federal financial aid such as Pell grants and student loans -- restricts cash flow in part because sanctioned schools must seek reimbursement of money rather than receive it in advance. Of 69 schools that have the same restriction as Arkansas Baptist, 13 are U.S.-based private, nonprofit colleges, according to the Education Department.

Fall enrollment dropped over the span of several years, from a 10-year peak of 1,193 in 2011 to a low of 575 last fall, according to data from the Arkansas Department of Higher Education.

Hill, hired in 2006, often is credited with reviving an institution that was on the brink of collapse.

He presided over extraordinary enrollment growth and oversaw an extensive makeover of the college's campus, including the remodeling of the Old Main building, the construction of new facilities and the purchase and razing of neighborhood eyesores and crime hot spots.

To complete the capital projects, the college accumulated debt through several loans, which it consolidated when accepting a federally backed $29.9 million loan in 2014.

Hill announced in February 2016 that he would resign from Arkansas Baptist, during the accreditation issues, with about four years remaining on his contract. His salary was reported in fiscal 2016 as $230,000, according to the college's tax filing.

MISSPENDING CLAIMS

Arkansas Baptist misspent at least $475,000 related to federal grants, most of which was meant for an endowment fund that was never created, according to the Peachtree assessment.

The federal Education Department since 2013 has granted Arkansas Baptist an average of $1.4 million per year from a type of Title III funding that is set aside for historically black colleges and universities, according to its website.

The Peachtree report says $150,000 in such funding and a $150,000 college match were earmarked for an endowment fund, but the money was "drawn and spent for other purposes." Arkansas Baptist does not have a single endowment or savings fund, it says.

It's not clear from the report when the college received the $150,000 or how it and the match were spent. Jones said it was in fiscal 2016.

Additionally, the report says, "At least $175,000 of invoices is outstanding for unpaid Title III funded contractors, for which the Title III funds have been drawn and used to pay other institutional obligations."

It does not go into detail.

Jones said he believes contractors working on the Derek Olivier Research Institute for the Prevention of Black on Black Violence, funded with Title III money, were not paid on time.

The Title III issues were just part of the broader problem of outstanding liabilities, the report said.

Jones said the college owed the Education Department roughly $700,000 in Title IV money it spent from 2013-15. That did not include liabilities from fiscal 2016 because they had not been calculated yet, he said, estimating the total would be closer to $1 million.

Those liabilities include drawing financial aid on behalf of students who were no longer enrolled or overdrawing money for students, Jones said.

Arkansas Baptist was setting up a payment plan with the Education Department when Jones left, which the board of trustees knew about, Jones said.

Jones said he does not believe the college followed through with the payment plan.

"I believe that's the reason why the [federal] money has stopped going to Arkansas Baptist," Jones said. "They gave us forewarning that this was exactly what was going to happen."

For context, Arkansas Baptist's spending totaled $17 million in fiscal 2016, according to its tax filing.

BILLS MOUNT

The college has a long history of struggling to cover its day-to-day operating expenses.

As of last summer, Arkansas Baptist owed more than $2 million to vendors. Over 95 percent of those bills were more than 30 days late, the Peachtree report says.

A review of Arkansas circuit court records found 11 lawsuits against Arkansas Baptist for a combined $737,000 in delinquent payments since May 2014. Most of those vendors secured judgments in their favor and were later paid. Five were filed in 2014, five in 2017 and one in 2016.

While not paying its bills, the college also failed to collect tuition and fees from students, the accounting firm's report says.

The college wrote off some $10 million-plus in student charges as bad debt "in recent years," the report says. If operating "like most institutions," the college should have been able to recoup at least $8.6 million of that amount, which "would have been more than enough funds to solve ABC's current financial woes," it says.

A "very poor collection history" developed because the college sent no monthly statements to students, had no procedures to encourage payments before midterm or final exams and did not report delinquent students to credit bureaus, the report says.

The college's deferred-payment program began too late in the semester and lacked "legal language similar" to what would be included on a run-of-the-mill credit note, it says. The report also criticized the college's failure to require a guardian to co-sign what is essentially the extension of credit.

Students were aware that they were not expected to pay any tuition their financial aid didn't cover, Jones said.

"That was part of the culture, or the practice, of being at Arkansas Baptist," Jones said. "I always thought it was insulting to [students] to assume they could not pay and make this blanket assumption that every student who came to Arkansas Baptist was impoverished."

Under Jones, the college began sending monthly bills to students and threatened to cut off meal plans for those who didn't pay or agree to a payment plan, he said. The board of trustees resisted those efforts, he said.

The Peachtree assessment also describes a college with no central purchasing authority or purchase order system.

Procurement policies for business, such as obtaining competitive bids, authorizing invoices, budget compliance and inventory control, "are haphazardly followed," the report says.

"These are prime reasons as to why the College has trouble balancing its budget every year."

More than 20 credit cards assigned to departments and employees rack up charges of about $1 million per year, the report says, advising the college to reel in the practice. For comparison, the college in fiscal 2016 employed 290 people, according to its latest tax filing.

Information for this article was contributed by Aziza Musa, special to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

SundayMonday on 05/06/2018