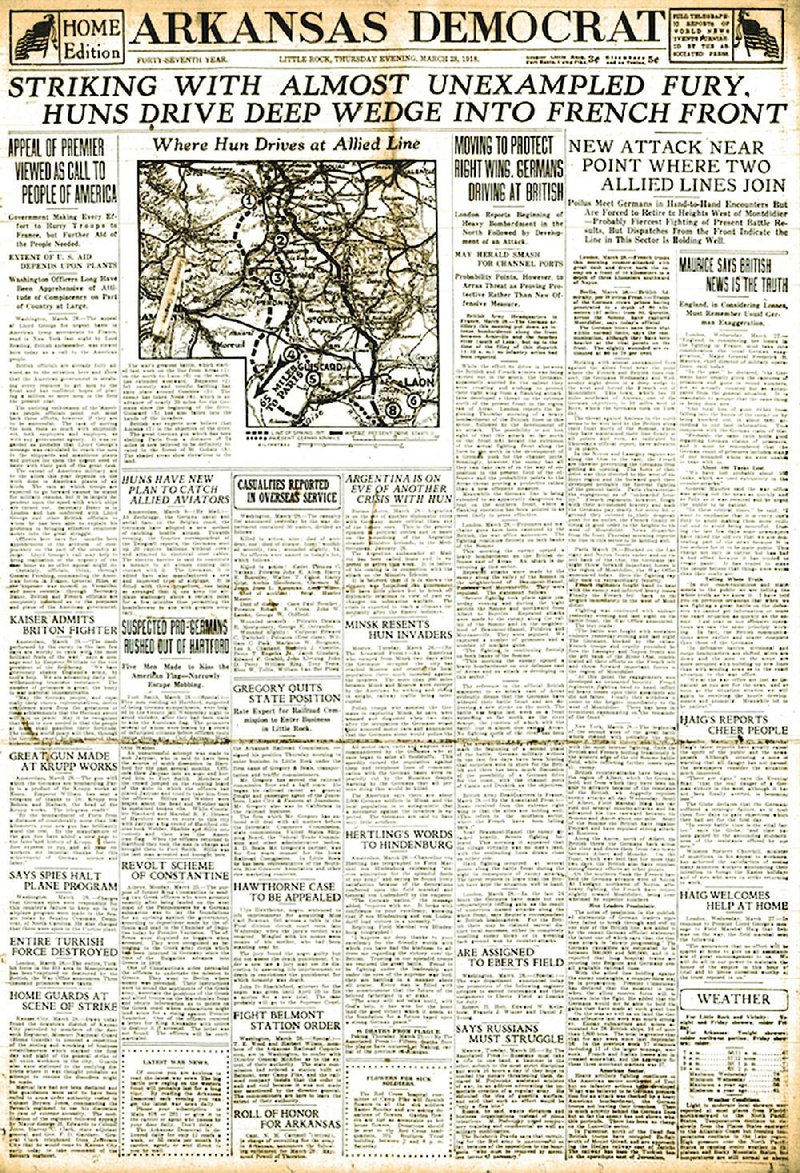

Front-page news in Little Rock 100 years ago truly was big news, remembered even today. It was spring, it was 1918, the Germans had opened a massive offensive along the 50-mile western front in France -- it was the German Spring Offensive of 1918. Die Kaiserschlacht.

Although the Kaiser wound up the worse for his work, from March 22 until April 2, bad news for British forces marched across the tops of daily Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat editions.

One of the most startling elements of the offensive was the Germans' new machine of war: a long-range cannon that was said to be blasting Paris from as far away as 74 miles. Inconceivable. Experts were dumbfounded.

Shells landed without the usual warnings. People thought at first they were dropped by Zeppelins, the long and sneaky, hydrogen-filled, high-altitude sausages that were hard to hear without special sound-mirroring gear.

But no, this was the Paris gun -- the "great Hun gun," as the Gazette put it.

Even the once-awesome howitzer Big Bertha (Dicke Berthe) couldn't clobber you from any farther away than about 10 miles (and by spring 1918, the worn out Berthas had been rotated out of action). It also was not Lange Max, a marine weapon converted for use on land with a range of about 20 miles -- no farther than 30 miles.

Stories in the Gazette quoted a chemist who speculated there might be a magnetic field around the Hun Gun barrel, keeping it straight; another expert thought the shells had to be made of tungsten. Or maybe there were little fans inside each shell? Maybe, unnamed ordnance officers suggested, the gun was actually hidden on the outskirts of Paris.

Amazing though it was, historians consider the Paris Gun a military failure -- its payload was small for the effort involved and the barrel wore out so rapidly that after 65 shots or so the enemy could only be sure of hitting someplace in the city. From March through August 1918, three of these guns shelled Paris but "only" 256 people were killed.

But as the Gazette reported March 25, as a "political cannon" it communicated that Paris was vulnerable. A weapon of terror, we would say.

Meanwhile, in downtown Little Rock, on the first day of the offensive, elevator operator "Old Man" Maxwell was trapped in his elevator in the Pulaski County Courthouse, all day.

The car -- a boxlike cage, really -- had metal-grating for walls, and the roof was solid metal. (What's that? You thought Old News was going to talk more about the Paris Gun mystery? ... Don't you know me by now?)

"Old Man" Maxwell was a prisoner at the county courthouse from 11:50 a.m. yesterday till exactly 5:13 p.m., without the formality of a warrant or an arrest.

As an "elevator chauffeur," the unnamed reporter says, Maxwell had experienced considerable success, but his car had been misbehaving.

Recently it stopped for several hours between the second and third floors, while two girls who work for the Eastern District [draft] Exemption Board were passengers. They have been walking to and from their office ever since.

At 11:49, "Old Man" declared he was going up and threw back the starter, but the car did not rise. His passenger was a rotund woman. He asked her to step off for a moment, and she did.

Slowly the car rose, till there was only a foot of grating above the floor of the elevator. Then it stopped.

Maxwell called for custodian Tom Fisher, "reputed to be the only person capable of repairing the refractory elevator."

Fisher worked on it three hours, until 3:30 p.m., when "more urgent business" called him to the county farm with Judge Lee Miles.

A Gazette reporter found Maxwell still suspended late in the afternoon.

Three rather prim ladies were pressing the signal button of the car in which Maxwell was prisoner. They were plainly vexed with him. For in answer to their repeated ringing he called "going up," but made no such move. Staring scornfully, they walked upstairs.

Maxwell asked the reporter to find Fisher, "but a trip out to the county farm after him was too much like work."

Maxwell had eaten a sandwich, but he was thirsty, so the reporter stood on a chair and handed a up a drink of water. He promised to bring some playing cards later so Maxwell could play solitaire through the night.

"I'm not going to stay here all night. Bring me a sledge hammer and I'll get out," declared Mr. Maxwell. The reporter did not hurry to comply, for the proportions of Mr. Maxwell are not such as to warrant belief that he could crawl through the one foot of grating showing.

Ouch!

In 1918 as today, there was another elevator in this "new" (1913) part of the courthouse -- on the other side of the main stairs. Assistant custodian W.W. Buford was in there, taking passengers up and down. Buford promised he would see what he could do to help Maxwell after he was through, since Fisher showed no intention of returning.

Finally, at 5:10, Buford ran his car to the top floor and, followed by the reporter, climbed a circular staircase to another floor, walked up a wooden incline to the top of the elevator drum and "pottered" with the machinery a bit. He pointed out the brushes and the mechanism to the reporter and then, at 5:13 ...

He moved a square-shaped, rubber-handled lever, commonly called a "switch," from its resting place into a socket. There was a flash, and then Buford turned a master-starter and the drum revolved creakily, while from below came the joyous shouts of "Old Man" Maxwell.

The last image the reporter gives us is of Buford, grinning. And nobody else saw that grin, he says.

The job of elevator operator was not a sinecure in 1918. Elevators were dangerous. From a story by syndicated answer man Frederic J. Haskin in the Gazette of April 8, 1920, we know that about 1,200 Americans were killed or injured annually by elevators. Most accidents were fatal. At least 80 percent of the accidents were caused by people stepping into open shaftways, or by the car starting before a passenger was all the way in or out.

By 1920, electric elevators had replaced the old hydraulic cars almost everywhere for passenger service. Safety devices were on the market as early as 1919 that prevented cars from moving until doors were safely closed. From an ad in the Jan. 31, 1919, Gazette, we know the Gus Blass Co. in Little Rock had installed a "positive action safety lock" on its passenger elevators.

But back to March 1918. Did Buford grin because he had easily accomplished something his boss, custodian Tom Fisher, had failed at for hours? Or was this an office prank? Did it have something to do with why people called Maxwell Old Man?

It's interesting to speculate, but the main thing to remember is we cannot know. We are just too far away from these long-gone Arkansans. At so distant a range, we cannot hit the target.

Email:

ActiveStyle on 03/26/2018