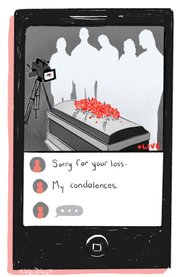

The whole experience was foreign for Kelli Zumwalt -- the Eureka Springs resident was in Panama, attending the funeral of a murdered loved one and the shiny lens of a camera attached to a tripod was focused on the casket.

Anyone who wanted to approach the body to say final goodbyes was on film, and the three cameras felt like 50, Zumwalt said. It was 2001 and the first livestreamed funeral she had ever attended.

"There were definitely family members that did not want to be on film, and did not go up to the casket," she said.

But it also let people who wanted to be there but couldn't travel the nearly 4,000 miles from Southern California to South America see the ceremony.

Since then, advances in technology have made the process of broadcasting funerals simpler.

Zumwalt's next experience was six years later, in 2007, and it was filmed with a laptop so an aging aunt in Indiana could watch from her room at the nursing home.

The most recent livestreamed funeral Zumwalt attended was sent via iPhone from the front row of the service a few weeks ago.

Web services such as this are growing more popular in the industry, said Randy Anderson, secretary of the National Funeral Directors Association.

Funeral homes are adapting to these changes, hiring employees with expertise in technology and offering more services -- virtual guest books, video presentations at the service and video recordings to take home. The increase in technology use has created an intricate, nearly impossible-to-untangle relationship between the Internet and the grieving process -- from social media posts nudging handwritten letters out of the process to virtually attended funerals and even to relationships with therapists becoming based partially on email.

The funeral home where Anderson works in Alexander City, Ala., is starting to put in the necessary equipment for livestreaming. He watched a funeral on livestream for the first time eight years ago when one of the other board members of the funeral association died in a plane crash.

The service was seven hours away, and he wasn't able to make it.

"I thought this was a neat thing that I was able to participate by watching that service," he said,

adding that webcasting is not designed to replace attending a funeral service, if at all possible.

In Harrison, Roller Farmers Union Funeral Home has been offering livestreaming services for eight years. They started doing it because several members of the military who were deployed were not able to attend their family members' funerals, said Aaron Gutting, a district manager for the home.

At Smith North Little Rock Funeral Home, Brent Hill said requests for livestreaming are scarce, so efforts are focused more on recording funerals to make DVDs for people to watch again later or send to absent mourners.

He said he does a lot of video work, but because of connectivity problems, he does less livestreaming.

"We've run into problems where the family may be in Timbuktu," said Hill, who has worked at funeral homes since he was 13.

. . .

Virtual bereavement may slow the grieving process after someone has died, said Elisabeth Sherwin, a psychology professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

"If you're there, you got to be a part of it even if only on a lower level or lower key," she said.

She said nothing can replace the human connection that comes from actually being there.

Ken Clark, a Little Rock therapist, said attending a funeral can help people move past the first stage of grief -- denial.

"Running from hurt and fear only ensures that you experience more of it," Clark said. "Ultimately, leaning into these things brings about reconciliation.

"The easiest way to not have cavities is to not go to the dentist because no one tells you you have problems, right?"

Clark said another way social media exercise new controls over the grieving process is through the therapy some turn to after a loss.

He said it's especially popular in Arkansas because it is rural and mental health services can be far away and difficult to access.

"As a practice, we're doing more and more video and telephone or email counseling over grief," he said.

Therapy through telemedicine is becoming more common in the state, particularly at community mental health centers, professionals across the state said. A telemedicine session is conducted over webcam, usually with supervision.

Clark said he often receives emails in the early hours of the morning, especially from clients who wake up from dreams about their lost loved one, which he brings up in later sessions.

But in his experience, after his father died of multiple myeloma, a type of cancer, social media posts helped him heal. Even though his dad died five years ago, the family still gets messages of condolence on Facebook, something Clark calls "vaccinations of remembering and grief."

However, Sherwin said, using social media posts in lieu of in-person conversation could be dangerous because of the self-selective ways in which people use the sites.

"Folks will write things on Facebook or share things they would never say to someone else," Sherwin said. "The degree of unveiling that people engage in is definitely at new heights, and it has been for a while."

Social media can establish a false sense of intimacy with people who clean up the messy parts of their lives for the Internet, Sherwin said.

Hill said he takes care of the social media accounts for Smith North Little Rock, and over the years, has made accounts on more mediums -- Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. Accounts show photos of some funerals and link to memorial videos.

Gutting's funeral home in Harrison is more focused on online guest books, where comments have to be approved before they go up.

"Every once in a while we get a negative comment, and we are able to moderate that," he said.

They also keep livestreaming of services private so only people with the link can access the video.

Sherwin said if links are not private, it's more likely that strangers who "like to go to funerals" will watch.

"It's a little bit like a genie in a bottle," she said. "You can't control it. You have to decide 'Am I going to make this available?' and 'Do I have the ability to control it?'"

One private Facebook group, which has more than 70,000 subscribers, shares links to livestreams of funerals, memorial pages or the social media accounts of people who have died. Most of the group's members live in Brazil, although it is an international group.

One post in early March shows a photograph of a young woman, tendrils of dark hair hanging in her face. Comments below the photo elaborate on how she died (her appendix ruptured) and offer condolences to her family and friends, whoever they are.

One comment included only a small image of a black cross.

The group's description says it's intended to disseminate information about the causes of death -- an online obituary. If family members see their loved one's photo posted in the group, they can ask for it to be removed.

The group has 12 rules of behavior outlined in the description. No profanity. No comments related to pedophilia. No contacting the family of the deceased. Members who break a rule are banned with no second chance.

. . .

Rhonda Owen, a Little Rock resident, said it wouldn't bother her if strangers had watched her sister's funeral in February.

"My sister was a lovely person," she said. "It would have given a lot of people a chance to get to know her."

Her sister Pamela Trawick had moved to California a couple of years before her death, and had friends from Arkansas, Colorado and South Dakota who wanted to see the funeral.

"We had as many people online as we did at the funeral," Owen said.

The church already had the capabilities to livestream because regular sermons are broadcast every Sunday. The cameras were hanging from the ceiling and were barely noticeable, she said. Owen watched the funeral again on a DVD later.

"It's kind of a blur for me," she said. "It was good for me to watch it."

Style on 03/25/2018