EUDORA -- No one in power cares what happens to kids in Eudora.

That's what Sam and Marion Jones are afraid of -- that when all is said and done, their son won't be able to get the help he needs, because he was born in a forgotten corner of the state.

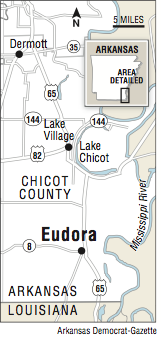

Eudora, a part of the 10th Judicial Circuit in Chicot County, is 8 miles from the Louisiana border and has just over 2,000 people. Nearly half of them live in poverty.

There's nothing for kids to do after school. No Scouts. No Boys & Girls Club. No Four-H Club program. Nothing, the Joneses say.

Their 17-year-old son could use a mentor or something to do to make staying out of trouble easier. He spends his days biking around town now that he is out of juvenile lockup. He hopes to join Job Corps in Little Rock soon.

"It's just like we don't exist," Sam Jones said. "We're just lost."

Many in the region don't have transportation, so they can't access the few services available, said Circuit Judge Teresa French, who handles juvenile-court cases. She thinks better transportation would help.

French also thinks that using evidence-based parenting classes would cut down on the area's juvenile probation cases.

Existing programs are often spread out. Mental health services can be 40 miles away for people living in Dermott and Eudora. Before a facility opened in Monticello, youths were going to Mississippi for treatment.

"Over the years, as the budget decreased, I have seen what they [programs] have been able to provide go down," French said.

Several programs for youths on probation are contracted through Phoenix Youth and Family Services. The nonprofit provides counseling and case management, but there's too much to do and not enough choices for kids.

"Clearly we are in a state of crisis," said Toyce Newton, president of Phoenix. "Something else needs to come into the picture to turn this thing around.

"We feel like we are at the ends of the earth sometimes," she added of her region. "I feel like we're kind of an afterthought. Why can't we get services like other folks?"

A lack of community resources isn't just a rural Arkansas problem.

In Pulaski County, there aren't enough mental health services for kids, Judge Patricia James said. She wishes juvenile court were a place where families could get wrap-around services, such as scheduling court-ordered counseling or signing up for mentors, and handle other court-ordered affairs, similar to a program in Santa Cruz, Calif.

Longtime juvenile-case Public Defender Dorcy Corbin also said there need to be more mentorship programs in Little Rock.

Craighead County doesn't have any affordable trauma-based therapy services for privately insured children, said Amy Powell, with the Arkansas Juvenile Officers Association.

Other judges say they have to work to find alternative ways to get kids services that don't use court dollars.

"There are still some very serious areas of need that at the end of the day will take financial support," said 20th Circuit Judge Troy Braswell of Faulkner County. "But we can't fall victim to say that we need money to make a change."

Braswell said he's teamed with community members to create programs that help kids.

In Clinton, Chamber of Commerce members teach financial literacy classes to older at-risk kids. Police officers exercise with children at Zumba classes. The library is hosting a new book club for at-risk girls.

Across the state, many parents are at a loss, even before their children enter the juvenile justice system.

For years, Vicki Richardson's son needed help. He shut down when adults tried to talk to him. He bullied his younger sister.

Richardson went to court and filed a Family in Need of Services petition, a legal avenue for children and their parents to get certain services, such as counseling.

The judge didn't help then, she said.

It wasn't until her son landed in juvenile lockup that he got help, the Jacksonville woman said.

After almost three years in lockup, doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder. Richardson wonders what their lives would be like if they had known that sooner.

"That's five years, almost six years now, we've been in the system," she said. "It's just time-consuming. It just consumed our whole life pretty much."

SundayMonday on 03/04/2018