Attorneys defending death-row inmates who are challenging the constitutionality of Arkansas' lethal injection protocol have asked to amend their federal lawsuit to add complaints related to the April 2017 executions of four prisoners.

In court documents filed this week, attorneys sought to add claims concerning "consciousness checks" that were part of the Department of Correction's protocol during last year's executions of four men in an eight-day period. The state executed inmates Ledell Lee, Jack Jones, Marcel Williams and Kenneth Williams.

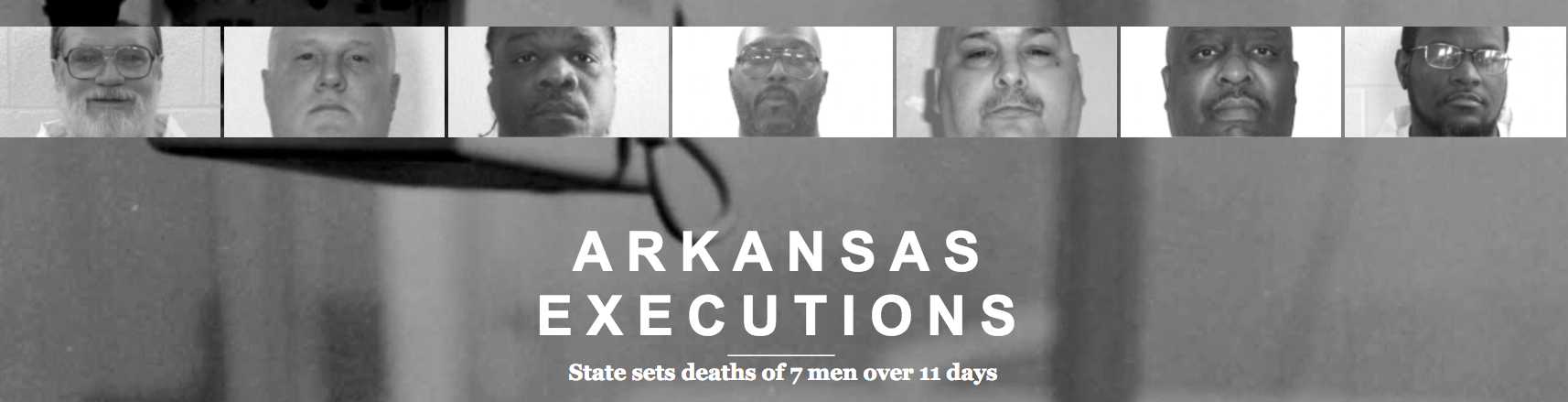

A lawsuit that the executed men were part of was filed last year and focused on the state's three-drug protocol, which attorneys say violates the inmates' constitutional rights to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. At the time it was filed, the state planned to execute eight inmates in an 11-day period, but court orders blocked half the scheduled executions.

Meanwhile, the lawsuit challenging the three-drug protocol, known as the "midazolam protocol" because of concerns about the first drug administered, has been set for trial the week of Nov. 26 before U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker.

On May 22, Baker granted a motion to intervene by 13 other inmates, allowing them to join in the case being pursued on behalf of Jason McGehee, Stacey Johnson, Bruce Ward, Terrick Nooner and Don Davis. All except McGehee remain on death row. McGehee remains a plaintiff despite his death sentence being commuted last year to life in prison.

The intervenors are death-row inmates Justin Anderson, Ray Dansby, Gregory Decay, Kenneth Isom, Alvin Jackson, Latavious Johnson, Timothy Kemp, Brandon Lacy, Zachariah Marcyniuk, Roderick Rankin, Andrew Sasser, Thomas Springs and Mickey Thomas.

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

According to the proposed amended complaint, the lawsuit takes issue with the department's "failure to properly perform consciousness checks during executions," and also challenges alleged violations of the prisoners' rights to access the courts and counsel during executions.

The state's lethal injection protocol requires a dose of 500 mg of midazolam, a sedative, followed five minutes later by a 100 mg dose of vecuronium bromide, a paralytic, and then an injection of potassium chloride, which stops the heart.

The new allegations state that between the first and second injections, the department's deputy director or his designee is supposed to "confirm the condemned inmate is unconscious by using all necessary and medically appropriate methods," but that the protocol provides no further detail about the nature of such "appropriate methods." It says that if the director or his designee thinks the prisoner is still conscious after the consciousness check, the executioners are to inject another 500 mg of midazolam.

But during the April 2017 executions, witnesses were unable to determine when each drug was injected, and there was no indication of when or whether the deputy director or his designee performed a consciousness check, the lawsuit states. It says that during several of the executions, the prisoner moved when he should have been anesthetized or paralyzed.

The proposed complaint describes events surrounding each execution separately, noting that Kenneth Williams "began bucking against the restraints so hard that it caused bruising to his head" and quotes a witness as saying he "lurched forward 15 times in quick succession, then another five times at a slower rate."

It says Marcel Williams was breathing heavily during the execution process "with his chest rising in hard, almost jerky motions," and that one eyewitness "noted eye movement until at least three minutes before the coroner was called."

The complaint says Jack Jones' lips moved after he completed his final words and then again about five minutes into the execution, according to a news reporter.

It cites other examples of possible problems during midazolam executions carried out in Ohio, Oklahoma, Arizona and Alabama.

The new allegations also argue that consciousness checks aren't applied consistently from execution to execution, and that the executioners either didn't carry out appropriate consciousness checks or proceeded with the execution even after the prisoner "exhibited movements indicating consciousness."

Although the department's protocol allows only one attorney to view each execution and bans communications with other attorneys or the court during executions, the court ordered the parties last year to negotiate an agreement that called for two attorneys to view each execution and that permitted telephone access during the executions.

The amended complaint states that to the plaintiffs' knowledge, the department "hasn't incorporated this policy into its protocol or otherwise ensured that it (or a similar policy) will be applicable to future executions."

It also complained about audio to the witness room being shut down after the inmate's last words are spoken, and said the department's policies prevent defense attorneys from having access to the entire execution, violating the prisoners' access to the courts.

The lawsuit contends that midazolam's sedative properties are limited and it cannot produce general anesthesia, while the paralytic prevents the prisoner from communicating any distress.

"Were there no paralytic, the arousal and pain caused by the potassium chloride would be obvious to any observer," the suit contends.

A batch of the paralytic drug expired earlier this year and no executions are currently scheduled in Arkansas.

Metro on 06/08/2018