Every night, each lamp was tucked into bed -- their bulbs carefully removed, shades set aside and blankets covering their electric casings.

As her dementia progressed, Beth Allen's mother went through a nightly routine of putting the lamps to bed, and Allen spent her mornings getting them up and re-dressed in shades and bulbs for the day. Eventually, she thought she could hide some of the lights that stayed in the lesser used rooms so it wouldn't take her so long to right the house every morning.

When her mother discovered the missing lamps that night, she was angry. Allen got a call from her sister, who was one of five siblings helping to take care of their mother.

"I don't know what you did, but Mom says you're never allowed back."

"What did I do?" Allen asked.

"She says you stole all her lamps," her sister said, laughing.

So Allen had to go over to the house, set the lamps back in place and apologize.

She cared for her mother during the day for two years before she and her siblings decided to seek professional help.

"Her realities were hers, and we had to work with them," Allen said.

That's advice she now passes along as a social worker at the University of Arkansas for the Medical Sciences. She's one of two social workers who helps patients and families in the Donald W. Reynolds Institute on Aging, and she runs a caregiver support group for Alzheimer's Arkansas.

The group, which ranges from six to about 15, is composed of unpaid workers who take care of loved ones. Last year in Arkansas, 177,000 people spent 201 million hours caring for their family and friends with Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia, according to a study from Alzheimer's Arkansas, a nonprofit that provides resources and research related to the disease.

There isn't a consensus on what causes Alzheimer's, but it manifests with plaques and tangles in the brain. Plaques are sticky proteins that build up between the forest of cells in the brain, hindering or halting communication. Tangles form inside dying cells, twisting until it is impossible for nutrients to reach their destinations.

These cells eventually die. A brain with late-stage Alzheimer's is substantially smaller than a healthy adult brain.

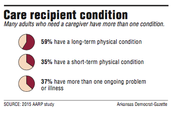

Thirty-five percent of the Arkansans engaged in caring for a family member are taking care of someone with Alzheimer's or other forms of dementia. The state has close to 500,000 of these unpaid caregivers, according to data from the American Association of Retired Persons. The others are working with people with physical ailments -- cancer, injuries from falls or surgery recovery.

No matter what the person needs care for, the task can wear on the caregiver, studies show. Many die before their loved ones, Allen said.

"I tell them 'I'm going to watch you, and the next time you come in and you look like you haven't slept and you're crying or you're losing weight, we're going to have a big talk,'" Allen said. "'Because we're a team, and I can't have you crash.'"

Estimates from various caregiving resource groups, including the online clearinghouse AgingCare.com, show that about 30 percent of caregivers die before the person they are caring for -- because of stress.

"Now the problem is when it all falls to the caregiver, they're under tremendous stress," said Herb Sanderson, director of the Arkansas branch of the AARP. He adds, "You can literally kill yourself caring for somebody."

RESPITE CARE

One of the best things a family can do is to just take a break, Allen said. Let someone else step in, however briefly. She recommends that caregivers in central Arkansas apply for one of the $500 respite grants Alzheimer's Arkansas offers.

The nonprofit also gives out other grants throughout the state for home improvements, funeral expenses and family assistance, said Elise Siegler, president of Alzheimer's Arkansas. These are usually about $300, and the nonprofit plans to award about $50,000 worth this year.

"They may take two hours here, three hours there, or they may take a whole weekend and take that break," she said. "But it's just so important that they take that break."

How far the money stretches depends on whether it's used to get professional care or the family hires someone they know to stay with their loved one, said Luke Mattingly, president of Central Arkansas CareLink, which provides resources to senior citizens.

Professional care is expensive -- it could cost up to $25 an hour, and in rural areas the option might not exist. Allen remembers spending a day looking in vain when several unrelated patients from eastern Arkansas came to Little Rock in search of services, but she didn't have any connections near any of their homes.

"We have a lot of black holes in the state of Arkansas, really bad ones," Allen said.

"There are very few daycares, no assisted livings, it's very rural, very poor. Transportation issues. No resources. I mean, it's a struggle."

SUPPORT IN NUMBERS

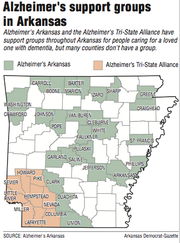

Alzheimer's Arkansas has more than 50 support groups across the state. Many counties in the Delta don't have groups, something Siegler said she is working to change.

Stephenie Cooke leads a group in Helena-West Helena. She started volunteering after experiencing how scarce help was in her region when she helped her family care for her grandmother.

"As a result of going through all of that, then I wanted to do something to help other people going through the same thing," Cooke said.

She said it has gotten easier since her caregiving experience because of the education groups like Alzheimer's Arkansas provide, but it's still hard to get help in Phillips County.

Growth in the elder caregiving industry has been mostly in more populous counties, Mattingly said.

The industry grew explosively -- first in 1999, when the Arkansas Legislature passed Act 1537 that allowed private care agencies to operate under Medicaid, Mattingly said.

When he came to work at CareLink, the nonprofit only had about six competitors. After the law passed, the number grew to more than 60, but that was mostly in metropolitan areas.

"I still don't have competition in Lonoke County," Mattingly said. "Nobody will do it out there."

MANY ROLES

Last year, CareLink workers provided 476,304 hours of paid care. These workers aren't trained to provide medical care; they can help with things such as preparing meals, bathing and getting out of bed, Mattingly said.

To be certified to provide medical care in someone's home, employees would have to go through at least 35 more hours of training, he said.

AARP released a study in 2015 that showed family caregivers were increasingly performing tasks traditionally done by nurses -- injections, tube feedings or catheter care. About three out of every five family caregivers reported doing at least one of these tasks.

This adds to the stress of caregiving, those surveyed for the study said. Most who were providing medical care had no training.

"They have to be doctor, nurse, social worker, nutritionist, pharmacist, grocery shopper, housekeeper -- all these roles that they've never had to do by themselves," Siegler said. "It's overwhelming even to the most healthy of persons."

Arkansas has been working to change this. In 2015, Gov. Asa Hutchinson signed the Arkansas Lay Caregiver Act into law.

The law allows a hospital patient to designate someone else as a caregiver. Hospital workers have to contact the designated caregiver about any changes to the patient's treatment and demonstrate after-care procedures if necessary, Sanderson said.

"It certainly has helped, but it's not going to increase dramatically the family's ability to do things," Sanderson said. "And not everybody has a family member. So it's helpful but it's certainly not a silver bullet for challenges to families."

Mattingly said he has seen more people without family nearby, so the burden of their care falls on a spouse.

Linda Austin, 71, took care of her husband, Jerry, until he died of cancer, eight days before his 74th birthday this year. He went through 40 rounds of radiation, took pills, got shots and had therapy, but it wasn't enough.

"We ran out of treatments," Austin said.

Most of his care was chores she would have been doing anyway -- cooking and laundry -- but the medicines and helping him bathe and dress were new.

Beth Allen's support group includes several caregiving spouses. One member continues to attend meetings even though her husband has died.

"Those older ones really fight to not let anybody else help at all because that's a commitment they made long ago," she said.

Such unwillingness to accept help means more stress for spousal caregivers, Allen said. She's especially careful to watch them for signs of self-neglect.

Austin was married to her husband for 53 years. After half a century of watching out for each other, she didn't consider it a burden to care for him. He died in their Eureka Springs home in March.

"I think he felt more comfortable with me taking care of him," she said.

Style on 06/03/2018