Even in this age of instant information, when a loved one is in jeopardy or might have died, we know the agony of uncertainty.

And so we can imagine what it must have felt like in July 1918 to have a family member off, somewhere, fighting the Great War. News trailed action by days or weeks.

Once a few kinks were worked out of communications among the Americans, British and French, the names of those killed, wounded or missing didn't appear in Gen. John Pershing's daily casualty lists until next of kin were notified. Those notifications might happen right away or they might take days.

Teddy Roosevelt had four sons in military service. Even though he was a former U.S. president, it took 48 hours before he was notified. On July 16, a cable from Pershing arrived at Roosevelt's home announcing that his youngest, Quentin, a fighter pilot, was missing in action in France.

The next day, Roosevelt learned from press accounts that witnesses, including a cousin, had seen the lieutenant shot down during aerial combat in the area of Chateau Thierry -- on July 14 -- possibly in flames, 10 miles behind enemy lines.

Teddy and Edith Roosevelt issued a statement that day expressing gratitude that Quentin had been able to be of some service "and to show the stuff there was in him before his fate befell him." Other sons, Archibald, a captain, was severely wounded March 11, and Theodore Jr., a major, was gassed in June. But Quentin was his family's pet, a "blessed rogue" remembered for his boyhood antics in the White House.

On the 18th, the press reported a "ray of hope" -- a relative in Paris had cabled that Quentin's death was not confirmed. The Arkansas Gazette reported July 20 that Roosevelt also had a different cable, from a son-in-law who was also in Paris, that Quentin was undoubtedly a prisoner.

And the Red Cross was searching for him.

Finally, July 22, the Gazette carried news of a Wolff Bureau report from Berlin confirming Quentin's death -- and burial by German airmen near Chambray. Wolff described his last moments as heroic; the Germans had buried him with military honors.

Glory is cold comfort, but at least they were sure.

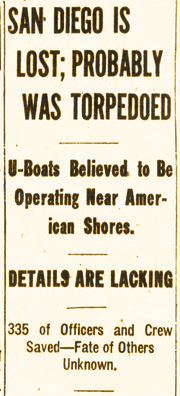

THE SAN DIEGO

Consider the families of Arkansas seamen serving aboard the armored cruiser USS San Diego in July 1918. This was the first of four U.S. vessels named for the California city; what happened to it is still a subject of marine research.

About 11:30 a.m. July 19, the San Diego was headed to New York harbor to pick up a convoy to escort: German submarines and mines were a constant threat along the Atlantic lanes. Ten miles southeast of the Fire Island lighthouse, an explosion rocked the 500-foot ship. Within 30 minutes, it capsized and sank.

The immediate report, carried in the Gazette on the morning of July 20, blamed torpedoes. Also, the Gazette reported that Lt. Rivers Carstarthen, 29, of Fort Smith, was presumed to be on board, and his family did not know his fate.

That afternoon's paper, the Arkansas Democrat, reported the ship likely had hit a German mine.

Did torpedoes or mines, or a saboteur, take down the San Diego? That's the mystery. We do know that all of the 1,180-member crew were saved, except six men.

But on the afternoon of July 20, the Democrat was able to report only that the crew abandoned ship in good order:

As the ship was turning over, the captain made his way to the side and jumped overboard. He and his executive officer were cheered by the men in the boats and as the cruiser went down the men sang "The Star-Spangled Banner."

But 48 men were missing.

Four days after the attack -- in the same paper that carried the burial of Quentin Roosevelt -- readers learned that another missing Arkansan, Jesse J. Foster of Stuttgart, had wired his father from New York and was OK. But, oh no, two other Arkansans were among the missing: John L. Williams of Plainview was feared lost; Charles H. Garrison of Jonesboro might have been on leave.

Might have been and was. On July 23 came word that Garrison had telegraphed his wife and parents.

He left here only two days before the sinking of the ship, and reached New York the day the ship went down.

Also July 23, the Gazette reported another Arkansan -- Chief Yeoman Paul Edwin Jones, 24 -- had just returned to the San Diego after a 15-day furlough at Dardanelle, Birta and Conway.

Mr. Jones was supposed to be on board when the San Diego sailed. Relatives have not heard whether he went down.

Good news came July 24 from Plainview, where Williams' brother had a telegram from the Navy. Also July 24, the Navy named eight men, only, as still missing -- none from Arkansas.

But assurances to the home folks were still coming in. July 28, S.T. Brown of the Harrison Canning Co. at Harrison told the Gazette he had a telegram from his son, Charles H. Brown, that he and three fellow sailors from Alpena, Charles Webb, Vaughn Thomasson and Roy McCurry, were fine. On July 29, McCurry's brother confirmed he had heard from Roy, who "had a good swim" for three hours before he was rescued.

Ten days after the disaster, relatives of Frank Westermen of Benton passed along news that he was safe in port.

THREE WILLIES

Here's a communications-theme incident from the July 24, 1918, Gazette. It happened at Camp Pike, the Army training cantonment in North Little Rock, where a new wave of draftees was reporting for duty.

Two men named Willie Turner from the same north Arkansas town had stepped off the same train to present themselves for service.

Willie No. 1 showed up yesterday with a bunch of draftees from his section and said that while he had been notified to report here for service he had been given no draft papers; had never received any, and, in fact, had never registered. He is 37 years old, he said.

While officials pondered this unusual man, Willie No. 2 showed up.

His case was very similar to that of Willie No. 1, although with reverse English.

Willie No. 2 had received draft papers and had registered, but had never been notified to report. After a while he grew interested in the government's intention with reference to himself. So he had gone to the local draft board to ask when he would be called. A clerk said he had already been called "and had better get out of town."

He caught the next train for Camp Pike.

The case was brought before receiving depot commander Lt. Col. John W. Barnes, who ruled that the notification card in the possession of Willie No. 1 had been intended for Willie No. 2, who had all the other papers.

But before the colonel made his decision official, he received a notice from that draft board stating that another case of Willie Turner had been found in the town, and that the notification was meant for him.

So pending the board's decision on Willie No. 3, Willie No. 2 is being held here. Willie No. 1 was dismissed as beyond the military age.

I suppose it's possible that the third Willie turned out to be merely Willie No. 2, misunderstood yet again, but if the Gazette followed up I can't find it. And so we must learn to carry on despite uncertainty.

Email:

ActiveStyle on 07/23/2018