School officials who work with homeless children say Arkansas’ plan for complying with federal education guidelines will help identify needs and keep more students in school.

The state’s plan for implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA, will rank schools on a variety of factors, including absenteeism.

Absenteeism affects learning, and children without stable housing are among the more likely groups to miss school, said Cindy Hogue, assistant to the state’s education commissioner.

And experts say many homeless students miss school because of toothaches.

Hogue was among more than 100 education and school officials from across the state at a conference Thursday and Friday who examined ways to reduce chronic absenteeism among homeless students through improved health care, among other strategies.

“What we know about attendance is if you’re not there, you’re not learning,” Hogue said. “… What we’re not paying attention to is those kids who are missing one or two days a month.”

The annual McKinney-Vento conference brings together schools’ homelessness liaisons, counselors, social workers and school administrators to discuss how to best help homeless children. The conference is named after a federal law that defines homelessness for people under the age of 18 and the government assistance available to them.

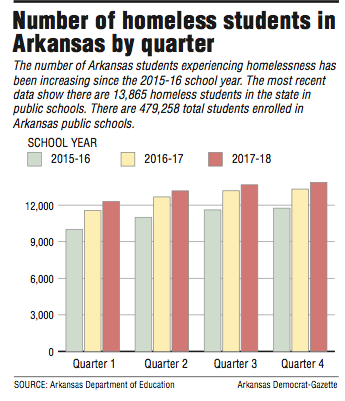

In the final quarter of the 2017-18 school year, there were 13,865 homeless students in the state, about 2,000 more than were counted at the start of October, according to data from the Arkansas Department of Education.

Discussion at last week’s McKinney-Vento conference turned frequently to the state’s plan to comply with the federal guidelines.

The Every Student Succeeds Act was passed in 2015 to replace the 2002 No Child Left Behind Act. The new law aims to allow teachers to focus more on individual students and their educational needs.

Arkansas’ plan for implementing the law includes continuous measures of student engagement, and absenteeism is a part of that, according to a memo from the education commissioner posted at the end of January.

Students are considered absent if they aren’t on school grounds unless they are on school business; it doesn’t matter if it is excused or unexcused.

Problems with absenteeism among homeless students often can be solved by regular trips to the dentist, said Jeri Clark, the school health services director for the state Department of Education.

“It’s probably not the all-being answer, but it’s a good move,” Clark said of the law. “I feel like it’s a good move.”

Bobbie Riggins, who has been the homeless liaison at the North Little Rock School District for 19 years, said she thinks the new act will be a game changer in helping students who don’t have a stable place to live. Riggins has worked most of her career under the No Child Left Behind program.

“I think it’ll be a lot more individualized,” she said. “Every child is different. Even in the household, every child is different.”

Students are considered chronically absent if they miss 10 percent of the school year — close to 18 days. About 1 in 4 Arkansas schools has chronic-absenteeism rates of 20 percent or higher, Hogue said during her presentation to school officials.

Absenteeism contributes to low numbers of Arkansas third-graders who are reading at their grade level, said Deborah Coffman, assistant commissioner of public school accountability, at the conference.

By the end of third-grade, about 70 percent of Arkansas children were below proficient at reading, according to data from the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count report. The count is an annual ranking of how favorable conditions are for children in every state. Arkansas ranked 41st in the most recent report.

“When half of your kids are reading under grade level, we have a systemic problem, don’t we?” Coffman said at the conference.

The Education Department developed an index to rate schools under the Every Student Succeeds Act, and if a student is present most days of the year, the school receives a full point, but as they miss more school, the point gets fractionally smaller. Data on absent students are a “small sliver” of the ratings, but they are counted, Coffman said.

“Our [Every Student Succeeds] school index first calculates what each child has done, and pulls that together for the school score,” Coffman said. “That’s really exciting. That’s what student-focused education looks like.”

Students who have pain from dental problems are three times more likely than other students to miss class, and for homeless students, visits to the dentist can be few and far between, Clark said.

She added that schools with a health center on or near campus tend to have decreased absences.

Lisa McNeely, a social worker for the Bryant school district, said the school health center has been one of the most helpful resources for her in working with homeless children. A dentist treats students on Fridays.

“The whole concept is for a homeless student to be as successful as students who aren’t homeless,” Mc-Neely said.

She added that she thought the new plan for the state education system would help workers to focus on students more individually and identify their needs.

Riggins, the homeless liaison for North Little Rock School District, said dental problems and no eyeglasses for children who need them are the two most common health problems she encounters.

“You’d be surprised,” Riggins said. “They don’t have toothbrushes.”

She’s worked with the Arkansas Department of Health to get students floss, toothbrushes and toothpaste, she said.

Part of the issue with getting dental care is because not many dentists work in Arkansas, said Rachel Townsend, who works with America’s ToothFairy: The National Children’s Oral Health Foundation. The North Carolina-based group works to improve the dental health of children and access to oral care.

Arkansas doesn’t have a dental school, so fewer dentists wind up working in the state, she said. The group is working to develop incentives for dentists to move to the state, especially to rural areas.

Trey Stevens, the elementary school principal and homeless liaison at Glen Rose School District, said medical problems, some of which he thinks could stem from dental problems, are the most common reason for students to miss school, although the elementary had good attendance last year.

The district, which is in Malvern, has about 1,000 students. Stevens has been liaison for the past year.

He said he’s hopeful that Arkansas’ education plan will help him focus on homeless students.

He’s working on being more attuned to the needs of high school students, and trying to help them go to college, because his background is in working with elementary school.

“I think it’s going to help to pinpoint where the issues are at,” he said.

Students are considered chronically absent if they miss 10 percent of the school year — close to 18 days. About 1 in 4 Arkansas schools has chronic-absenteeism rates of 20 percent or higher, Hogue said during her presentation to school officials.