John Bell Jr. wouldn't be entirely happy about the exhibit of his work currently open at the Fort Smith Regional Art Museum as part of the city's bicentennial celebration.

The museum director knows it, even though he never met Bell.

FAQ

‘Fort Smith Legend

John Bell’

WHEN — Through April 22

WHERE — Fort Smith Regional Art Museum

COST — Free

INFO — 784-2787

BONUS — The video “John Bell Jr.: The Man Behind the Legend” can be viewed at fsram.org.

"From everything I've heard, he would have been very unhappy with anybody even considering viewing him through the lens of his disability," says Louis Meluso, whose first task after he came to FSRAM Nov. 1 was gathering the art for the Bell exhibit. "But he overcame so much."

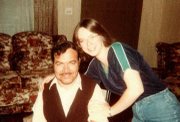

Bell's daughter is equally sure of her father's reaction.

"He was very interested in his artwork standing on its own," says Lisa Murphy of Conway. "He didn't want people to know he had a disability at all, because he didn't want his artwork to be purchased for that reason."

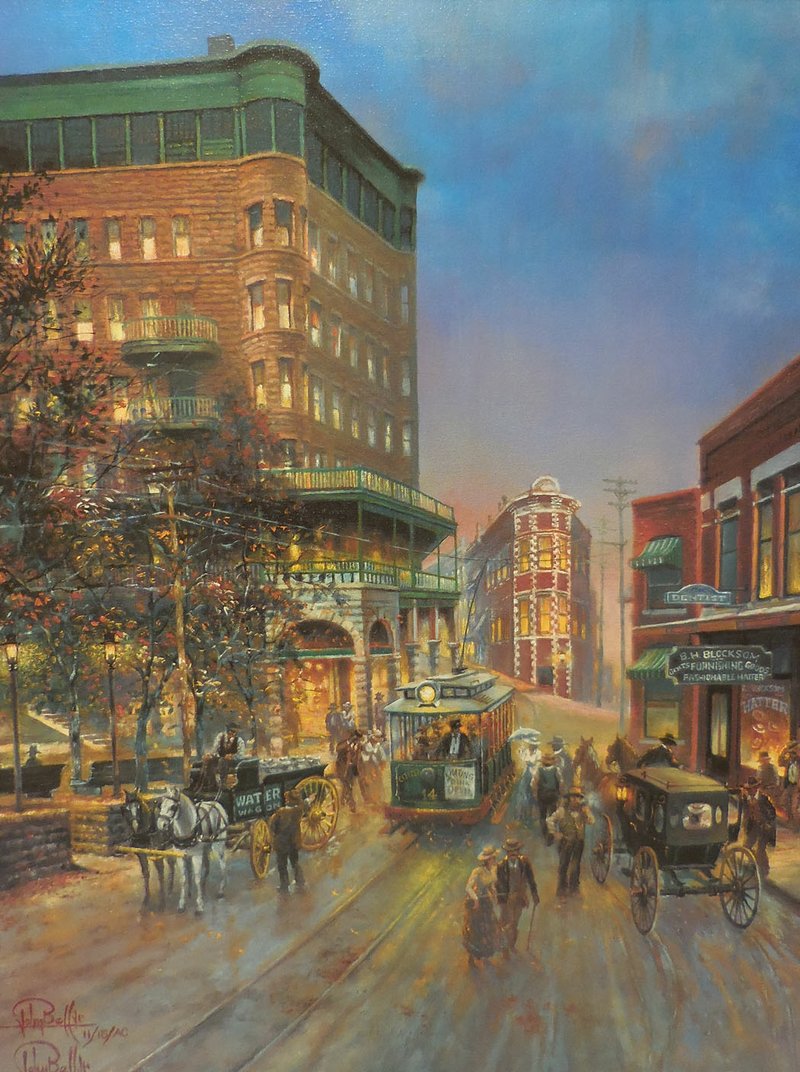

But Bell's story is unique and can't be properly told without including the fact that he was born in 1937 with cerebral palsy; his wife, Maxine, had polio; and they raised daughter Lisa from their wheelchairs. In spite of the challenges, Bell earned a regional, if not national, reputation for paintings that captured both the heritage of the state he loved and its magic.

"I can still remember chugging T-models, the ice man, anxiety about the war, radio plays, back yard clothes lines with sheets flowing in the breeze, and those small things that form the foundation for your life," Bell wrote before his death in November 2013 at the age 0f 76. "My parents came from coal miners and farmers in eastern Oklahoma, but moved to Fort Smith to start a new life. I was born here along with my two sisters and a brother. All of our memories and influences are of eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas, which is reflected in my art."

"Dad always said art has meaning according to what its purpose is," Murphy remembers. "You could do a pretty good pen and ink or watercolor or gouache of a church, make it look just like the church, add some cars and trees, but you bring community and purpose in when you show people coming and going from the church service. When you look at his paintings, they all show community, the actual spirit of what might be happening at the time. If he was going to paint Garrison Avenue, he was going to paint the parade, because that was a big 'purpose' for the avenue."

Murphy's first memories of her dad as an artist date back to a little art shop he had in downtown Fort Smith.

"It was in an old carriage house that went along with the home the Fort Smith Art Center was in," she remembers. "He and a partner had art supplies for sale, gave lessons. I think he sold some paintings from there. But what I remember most was the smell of turpentine. That's the stuff that sticks with you when you're a kid."

Murphy says she was always interested in art and took some lessons, but it was "really hard to be the daughter of an artist that's pretty well known. I wasn't handed that spoonful of talent. They expected me to be awesome, and I wasn't." Instead, she pursued a career related to the disabilities she accepted as ordinary in her childhood, becoming a vocational rehabilitation counselor.

"I was always a daddy's girl," she says. "I just didn't know there was anything different about him -- or Mother -- until I started school. Then kids tell you stuff."

Although he wanted his disability separated from his art, Bell was president of United Cerebral Palsy and traveled nationally in the early days of the Americans With Disabilities Act. Part of the exhibition of his work at FSRAM includes a video of "some of the people that knew John best" talking about their memories of the man and his art. "It adds not just a multimedia component but really brings to life the man as people knew him," says museum director Meluso. "And some of those stories are just tremendous and heartwarming."

Meluso came to the museum from the Art Institute of Chicago after a tenure of 13 years at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and previous experience at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The Bell exhibit was already on the schedule, he says. "It was just left to me to execute it -- which was a lot more involved than I thought."

Many of the 65 pieces in the exhibit were loaned by private collectors in Fort Smith, "so it was a matter of me doing the shoe leather work and going around to all these homes and businesses and the courthouse," Meluso says. "It was a wonderful introduction to the town."

The Bell exhibit is a perfect example of what Meluso was seeking when he took the job at FSRAM.

"I wanted to go someplace where I could make a difference and see that difference," he says. "Where I could help create the cultural fabric of the community -- John Bell was already such a big part of that -- and where the community could really benefit from my experience."

NAN What's Up on 01/21/2018