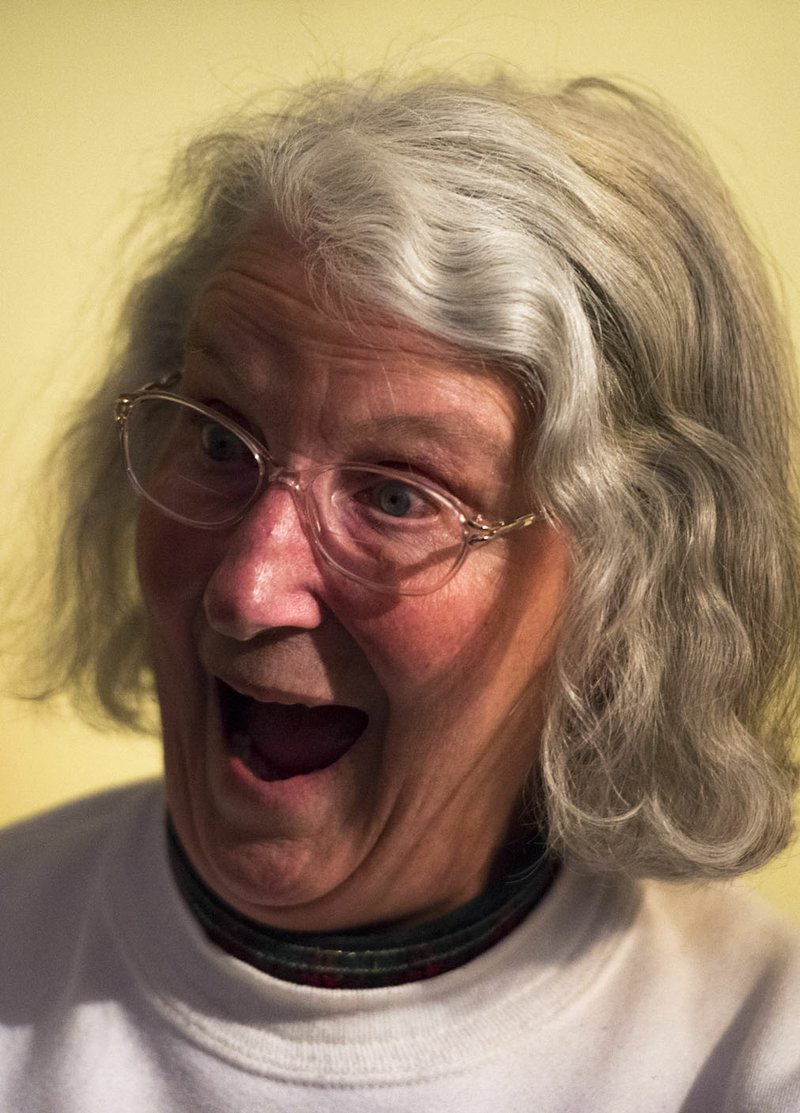

Ann Linkous sat on one of a pair of matching recliners in her Rogers home. She and her husband moved there after learning she had Alzheimer's disease.

Mark, her husband of 63 years, whistled in the kitchen as he opened pill bottles to prepare her medication -- one of many daily tasks he's undertaken as her full-time caregiver. It's nearly time for dinner, and Mark has assumed those duties as well.

Donate

Ann and Mark Linkous have raised more than $5,000 for Alzheimer’s research since September with their “sock ministry.” Anyone interested in donating can visit their Facebook page, called Sock it to Alzheimer’s.

"Miss Ann, would you like to set the table?" he asked.

Ann shuffled to the kitchen as Mark tore into a bag of frozen salmon. She set two plates.

"We'll need a napkin, a fork and a spoon," he dictated.

He placed the frozen fillets on a pan, moved them to the counter and began to apply olive oil with a brush. Ann reached her hand to help.

"I got it," he said with a gentle inflection.

"I have to watch him and make sure he does it right," she said jokingly.

Both shared in the laughter. Jokes and banter keep the mood light. He was never much of a cook, he admitted. Ann had 60 years of recipes, some passed down through her family.

"It was hard," Ann said about relinquishing control. "To not get to do what you'd been doing for so long. I get frustrated and down."

Mark won't let that happen, he insisted. He knows they have a long journey ahead of them from his experience taking care of his mother, who died from the disease in 2001.

Mark is one of the 15 million unpaid caregivers in the United States and one of an estimated 176,000 in Arkansas, most of them loving family members, according to the local Alzheimer's Association chapter in Rogers. Mark uses the help and resources available in Northwest Arkansas for caregivers and patients.

And he fights back by raising money for research.

Relinquishing control

Mark began to notice changes in Ann's behavior in 2012.

He remembers walking into the kitchen. She had ingredients laid out on the counter, and she was standing there holding a recipe and crying. Other times, he saw her struggle with the computer or her phone or trying to pay a bill.

"I already knew what was going on, but I was in denial," he said.

Ann and Mark had their first date on Valentine's Day 1954, and 60 years later, they would set up an appointment with a neurologist on Valentine's Day. That's when it was confirmed: Ann had Alzheimer's disease in the early stages.

Ann, 83, kept her usual routine for another year or two. Mark, 86, didn't realize how much she did.

"I felt bad watching her sit there reconciling a bank statement," he said. "She was going to make sure she did it. Finally, one day, she just kind of suggested I do it, but I wanted her to do as much as she can for as long as she can."

The Linkouses moved to Rogers from their retirement lake house on Beaver Lake in 2014. Ann hasn't driven for three years. Mark manages all of her medications. These are all steps to mitigate risks because Alzheimer's disease in the early stages can affect both long- and short-term memory.

But Mark often operates in a gray area.

"The most difficult thing is to find that line. They tell you that the caregiver should allow the one with the diagnosis to do everything they can do for themselves," he said.

Mark struggles with the degree to which he intervenes in her life. He must be an advocate at times, anticipating needs and potential problems before they occur. At other times, he's learned to pull back.

One evening, Mark got out a stack of photographs from a plastic bag and set them down one by one on the kitchen table. He placed a picture down of Ann when she worked as a church secretary at Immanuel Baptist Church in Rogers, a smile beaming from her face as she sat next to a group of children.

"Well, I just enjoyed doing the ... doing the ... getting everything together and making sure that is done and ...," Ann trailed, wrestling with the memory.

"Getting all the music ready in choir," Mark intervened.

He intervenes a lot, he admitted, and he has had to learn restraint.

"I don't want to interrupt, but I don't want to see her struggle, and that's kind of a fine line," he said.

What Ann can recall decisively about her involvement in the church is how she felt.

"I enjoyed it," she declared.

Care-taking mom

Mark keeps a picture of his mother tucked in his Bible, the last photograph of her he wants to remember.

"That's the way my mother looked about the time, just before she had problems remembering who we were," he said. "Most of the time, she knew Ann and I. I don't know if she knew other members of the family as long as she knew us."

The disease started mildly. Mark first noticed his mother could no longer balance her checkbook. Then she started to miss bill payments.

"Initially, we weren't sure it was that. Sometimes you think, well it's just old age. And then you finally realize there's more," he said.

Then a woman who helped his parents around the house discovered his mother had placed a soiled pillowcase in the oven to dry it.

Mark and Ann would make the long drive each month to south Arkansas to trade care-taking duties with his sister. They did the housework, cooked and managed his parents' medications.

In 2000, they moved his mother to hospice care in Rogers. The final year was tough, Mark recalled. Both his parents shared a room in a nursing home.

"Most of the times, she was a slate," he said of his mother toward the end. But at times, when she could remember, she would ask him to sing to her. "I'd sit there and sing and sing and sing," he said.

She remembered Ann for a moment and asked Mark to tell her she loved her. He believes God gave her that window.

"You can always find a bright side if you look hard enough," Mark said, reflecting on the story. "We're blessed it was later than earlier. You can say you've already had a lot of good years. The people I feel sorry for are the ones in their 50s and 60s."

Finding help

Mark felt ill-prepared for his caretaker role, despite his experience with his mother.

"All I knew is it was some form of dementia. I didn't really realize what to expect. I didn't realize the steps. I didn't have anything like the playbook that is put out by Broyles Foundation that outlines what you can anticipate," he said.

Barbara Broyles, the wife of then-University of Arkansas Athletic Director Frank Broyles, developed Alzheimer's disease. Her family, who cared for her, put together a playbook in 2006 for caregivers and established the foundation. The book guides caregivers through the stages of Alzheimer's. Barbara, and later Frank, both died from complications from the disease.

After Ann's diagnosis, a friend suggested they attend a support group. Mark was hesitant. It felt too soon and could be depressing if they got involved with others on the same journey, he thought.

Then, nearly two years later, he discovered a program called "Creative Connections" at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville. Through the guidance of a museum educator, caretakers and their loved ones look at art pieces and discuss their thoughts and feelings. Afterward, they create art together.

The program opened his heart to hearing other's stories, Mark said, and connected them to Shevawn Dillingham, special events coordinator of the Alzheimer's Association chapter in Northwest Arkansas.

"No. 1 is the stigma associated with the disease," Dillingham said. "It's so difficult for someone to come to terms with the disease first of all. A lot of times, people will think like Mark did: That it's just going to be depressing, and it's not going to help."

Dillingham introduced Mark to Brandi Schneider, director of aging and administrative services at the Schmieding Center for Senior Health and Education in Springdale. Schneider, who specializes in early stage diagnosis, invited Mark and Ann to a program at the center. For eight weeks, caretakers and their loved ones received information including how to manage assets, living wills and trusts.

"It starts with getting your legal house in order," Mark said.

Finally, they learned how to stay ahead as the disease developed, when considerations about in-home care, nursing homes -- and at the late stage -- hospice care become more relevant.

"We've been very blessed that Ann's has moved very slowly, but you never know how long that will be the case," Mark said. "So we began to make a list of all of the things we needed to do."

Mark and Ann also collect donations for research. Their efforts include starting a nonprofit in August called "Sock it to Alzheimer's" as a way to raise money and inspire discussion about the disease.

"In my mind, if you're a caregiver, you walk everyday for Alzheimer's. I'm going to go find several pairs of purple socks and start wearing them every day because I walk for Alzheimer's everyday," Mark said.

Mark's idea grew into what he calls his "sock ministry." With the help of his daughter, he was able to make a friend in the apparel business. Together, they designed a logo and six different sock design.

"Our children have it on both sides of the family," he said. "I feel pressured in a sense to do everything I can to help raise funds to find a cure."

NAN Our Town on 02/15/2018