U.S. Sen. J. William Fulbright knew about the Pentagon Papers for a year and a half before The New York Times broke the story in June 1971.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which Fulbright, D-Ark., chaired, acquired about 3,000 pages of the 7,000-page study in February 1970, three months after Fulbright learned of its existence.

But Fulbright didn't believe he had the authority to "unilaterally declassify" the copies his committee had stashed away in a vault, said Hoyt Purvis of Fayetteville, who was Fulbright's press secretary from 1967 to 1974.

Instead, Fulbright tried repeatedly -- and unsuccessfully -- to get Defense Secretary Melvin Laird to provide the papers to his committee. That way, the papers could have been made public, and there would have been no questions about how the committee got them.

Fulbright's committee received its documents from Daniel Ellsberg, a "volatile personality" who had "obviously broken the law," wrote Randall Bennett Woods in his 1995 book, Fulbright: A Biography.

Having Fulbright release the documents would help legitimize what some might characterize as an act of espionage, and it would have shielded Ellsberg from prosecution, wrote Woods.

There's been a renewed interest in the Pentagon Papers since the movie The Post came out in December.

The movie, which is still playing in Arkansas theaters, focuses on Katharine Graham, publisher of The Washington Post, and her decision to publish the Pentagon Papers after a federal court order temporarily stopped the Times from publishing its series on the topic.

Fulbright isn't mentioned in the film.

What became known as the Pentagon Papers was a "top secret" study commissioned by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in 1967 on the history of policymaking on Vietnam, going back to 1945. It resulted in a 47-volume, 7,000-page report.

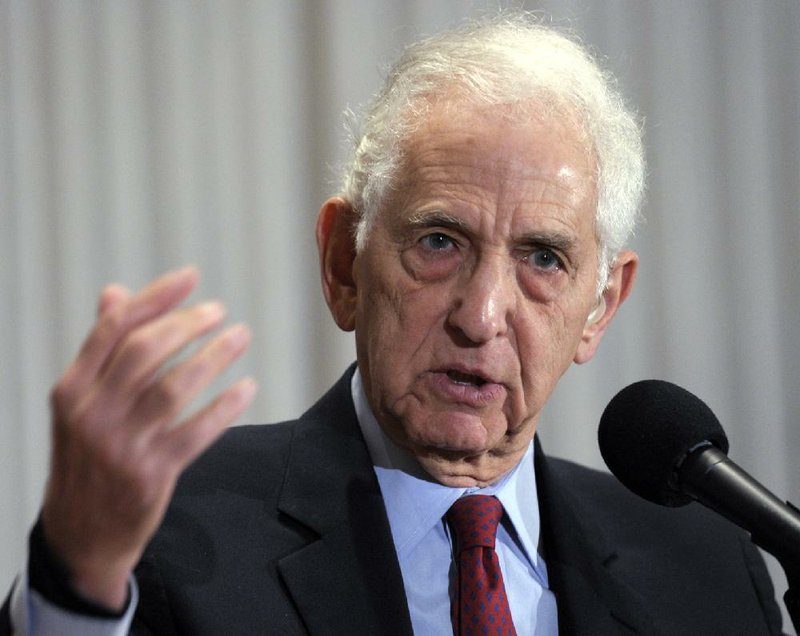

Ellsberg was a former military analyst who worked on the study and had made photocopies of much of it.

He approached Fulbright, a Democrat, in November 1969 to try to get him to release the study, said Purvis.

In that meeting, Ellsberg described the papers as "a sordid tale of deception and ineptitude" surrounding the war, wrote Woods.

Fulbright, a vocal opponent of the war, thought the Foreign Relations Committee should see the papers and determine what should be done, Purvis said.

Instead of using the documents from Ellsberg, Fulbright wanted Laird to provide a copy of the Pentagon Papers to the committee, but that didn't happen.

According to Woods, this was a strategy unto itself. If Laird refused to release the papers and they became public later, it would discredit the administration of President Richard Nixon for its use of "executive privilege merely to cover up a trail of executive-branch misdeeds," wrote Woods.

If Laird refused to release the papers, Fulbright and his staff knew Ellsberg would find a way to make them public, Woods wrote. That way, Fulbright and his staff could keep Ellsberg at arm's length.

After unsuccessfully shopping the papers around to a few other lawmakers, Ellsberg turned to the Times, which began publishing excerpts of the papers on June 13, 1971.

Four days after the Times published its first installment, the newspaper ran an article saying Fulbright had known about the Pentagon Papers since 1969 but was unable to get a copy of the report from Laird.

In letters to Fulbright, Laird described the study as a "compilation of raw materials to be used at some unspecified, but distant, future date," according to the Times article. "Laird contended that the material was sensitive because contributors to the study had been guaranteed confidentiality."

On Oct. 27, 1971, Purvis wrote to Sanford J. Ungar, then a journalist, providing a timeline of Fulbright's knowledge of the Pentagon Papers.

On Nov. 6, 1969, Fulbright and some staff members of the Foreign Relations Committee met with Ellsberg, according to the letter, which is in the Fulbright papers in the Special Collections Department at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, library.

Ellsberg discussed the Pentagon documents and gave the senator some notes, wrote Purvis.

"He had notes about one aspect of the study and it may be that he had some of the documents with him," Purvis said of Ellsberg's 1969 meeting with Fulbright.

Five days after meeting with Ellsberg, Fulbright wrote to Laird asking that the Pentagon Papers be released to the committee, according to Purvis' letter to Ungar.

On Dec. 20, 1969, Laird wrote Fulbright declining to provide a copy of the study, saying that to do so "would clearly be contrary to the national interest," according to the June 17, 1971, Times article.

Fulbright pressed Laird on the issue in letters in January, April and July of 1970, according to the Times. On July 21, 1970, Laird again rejected Fulbright's request.

On March 31, 1971, in a meeting with Fulbright and Norvill Jones of the committee staff, Ellsberg "talked about his desire to bring the Pentagon papers to public attention in order to bring pressure on the Congress to end the war," Purvis wrote in his letter to Ungar.

"Mr. Ellsberg has been quoted as saying that the Pentagon history was turned over to the committee in 1969," Purvis wrote in the letter. "The best information I can develop, however, is that it was probably late February 1970 when he gave the material (except for a few documents given to Senator Fulbright in November) to Norvill Jones. These amounted to probably 20-25 of the 47 volumes. These were xerox copies totalling about 3,000 pages of the reported total of 7,000."

Purvis said what he referred to as "the Pentagon history" came to be called the Pentagon Papers.

Purvis said the documents from Ellsberg were immediately locked away in the committee's vault where classified materials were kept.

That jibed with what Woods wrote in his 1995 book, but Woods noted that Ellsberg sent some of the documents by U.S. mail from Los Angeles. Ellsberg gave the committee 25 volumes of the 47-volume study, wrote Woods, who is now a distinguished professor of history at the university in Fayetteville.

On June 13, 1971, the Times broke the story about the Pentagon Papers in a Page 1 article by Neil Sheehan.

The Nixon administration stepped in, and a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order preventing the paper from publishing more articles about the Pentagon Papers.

"Meanwhile, the Times contested the injunction, arguing that prior restraint was unwarranted and the public's right to know should prevail," Purvis wrote in a column for the Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. "With the Nixon administration also seeking an injunction against the Post, and with the Boston Globe joining in publishing material from the papers, the U.S. Supreme Court took up the case on an expedited basis."

On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled for the Times and Post and they continued publishing articles about the Pentagon Papers.

"In my view, far from deserving condemnation for their courageous reporting, The New York Times, the Washington Post, and other newspapers should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly," Hugo L. Black, one of the justices, wrote in an opinion. "In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam war, the newspapers nobly did precisely that which the Founders hoped and trusted they would do."

Jones died in 2015. According to his obituary in The Free Lance-Star of Fredericksburg, Va., Jones, a native of Princeton, Ark., moved to Washington at the age of 15 to work for Fulbright.

Ungar is author of The Papers & The Papers: An Account of the Legal and Political Battle Over the Pentagon Papers. A former president of Goucher College, he is now the first director of the Free Speech Project at Georgetown University.

Ungar didn't respond to emails sent to his office at Georgetown University.

Ellsberg couldn't be reached for comment. Messages were sent to two of his spokesmen as well as his son Michael Ellsberg. None responded.

Daniel Ellsberg, 86, has a new book out: The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner.

SundayMonday on 02/11/2018